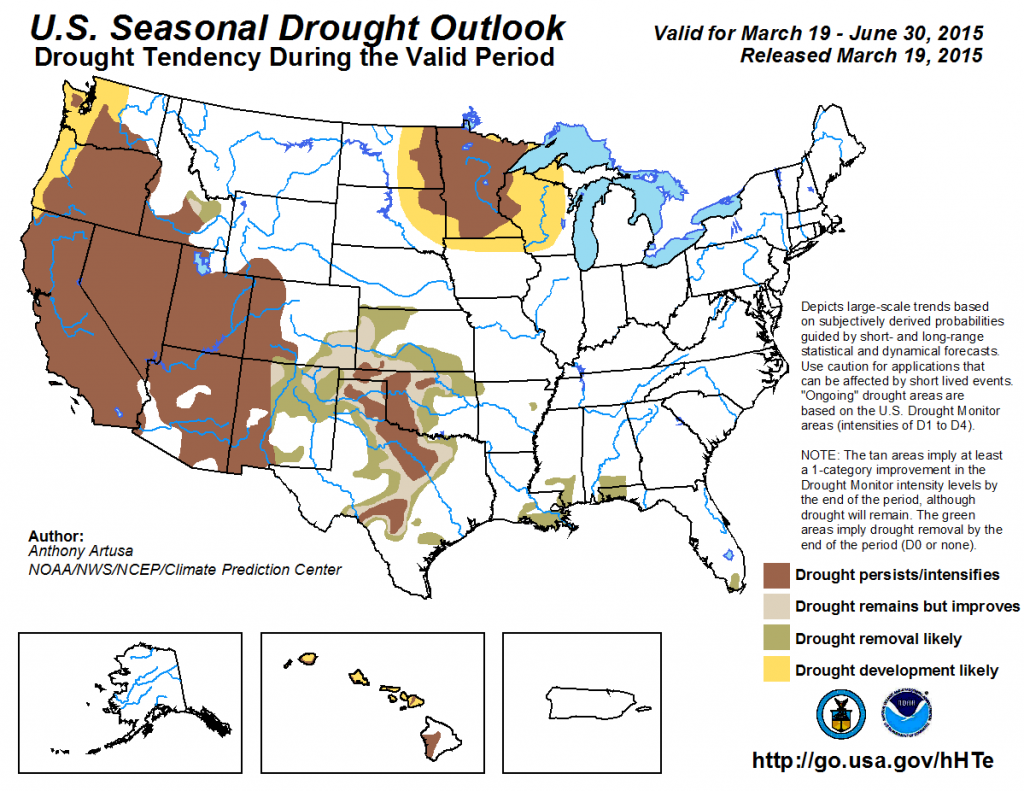

In a twitter discussion this morning, Brian Jordan shared a telling graphic that exposes the problems with Victor Davis Hanson’s recent City Journal essay about California’s water problems. Hanson’s argument is that California abandoned a dam-building program that, had it been pursued, would have provided the necessary storage to meet needs in this year of drought:

Had the gigantic Klamath River diversion project not likewise been canceled in the 1970s, the resulting Aw Paw reservoir would have been the state’s largest man-made reservoir. At two-thirds the size of Lake Mead, it might have stored 15 million acre-feet of water, enough to supply San Francisco for 30 years. California’s water-storage capacity would be nearly double what it is today had these plans come to fruition.

Hanson’s reflexive culture wars rhetoric makes him painful to read (“All the while, the Green activists remained blissfully unconcerned about the vast immigration into California from Latin America and Mexico that would help double the state’s population in just four decades”, capitalization in the original), but if you peel back what he’s saying, he’s really making an unexamined argument for the use of what David Zetland (pdf) calls “other people’s money” in providing water for his beloved agricultural communities in California’s Central Valley.

What he doesn’t say (and he really can’t, given the free market values that are central to his world) is that the dams whose lack he bemoans would have to have been built with “other people’s money” – the taxpayers of the state of California or the federal government. This is really expensive capacity, far beyond the financial reach of the farmers who would be using the water. And once you ask for other people’s money, their values come into play. (This would be the point, if I were adopting Hanson’s culture wars rhetoric, for the obligatory “welfare farmer” reference, but I don’t think that’s right, and I think neither that nor his “Green” and nativism frame are useful or correct – better to assume good faith on all sides.)

Jordan’s graphic of expanding storage capacity in Southern California’s Metropolitan Water District exposes the hole in Hanson’s argument:

Hanson notes Southern California’s substantial water storage reserves, but is blind to the reason they exist.

Met recognized the need for storage to provide, in drought, a more reliable supply of water for Southern California. Met spent its own money – billions over the years, according to Jordan, including hundreds of millions per year recently – to built the storage buffer that has enabled it to weather the current drought.

There are two important points here.

First, it wasn’t “other people’s money”. Metropolitan Southern California largely ponied up the cash to meet its own water security needs. This goes back to the construction of the Colorado River Aqueduct, which L.A. paid for itself.

Second, municipal users can afford to pay a lot more for water security. This is very expensive stuff, and I don’t think we’ll every see ag communities able to afford that level of reliability on their own. To get it, they need other people’s money, and at that point other people’s values come into play.