The notion of using “Las Vegas” and “sustainable” in the same sentence might give a lot of westerners the heebee jeebees, but there’s an interesting case to be made that its water management decisions over the last decade have pointed it in that direction. The Economist, in a look at Vegas water performance in its latest issue, doesn’t use the “s” word, but gives Vegas high marks for getting its water management house in order:

To the casual observer, with most of the West parched, Las Vegas’s water use seems astonishingly wasteful. Visitors flying in see acre on acre of suburban houses, a good proportion of them with pools. Those staying on the Strip find abundant fountains, enormous swimming pools and palm-lined boulevards, all in the middle of the desert. And yet beneath this mirage, quietly, Sin City has proven remarkably effective at managing its water, even as its population booms.

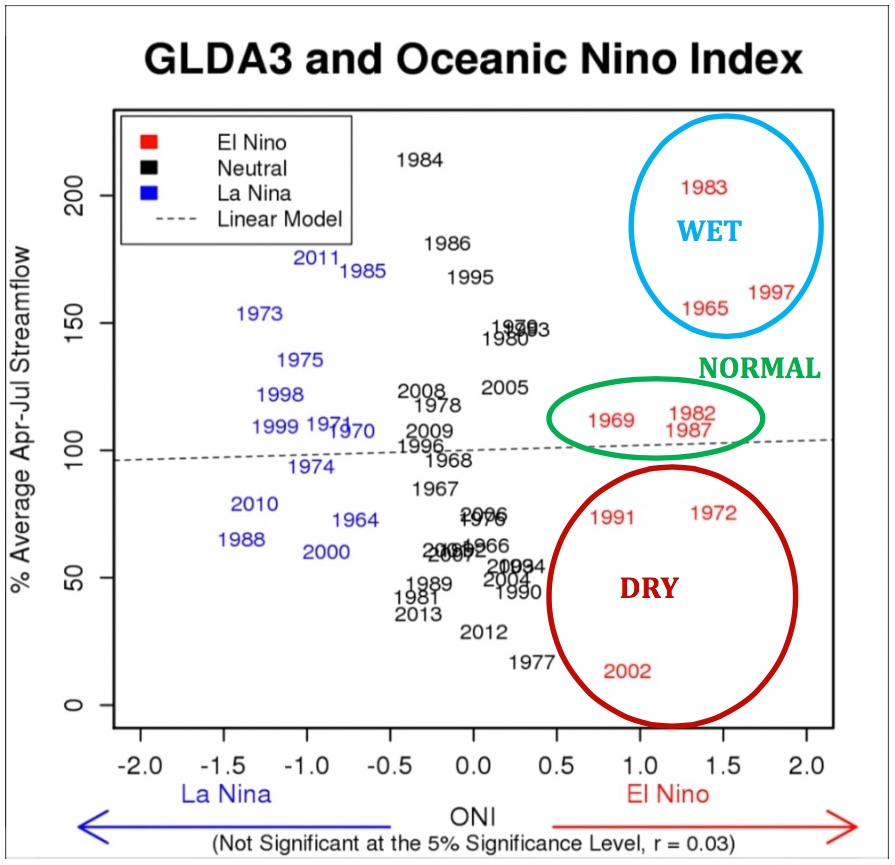

Talking to some folks today who are working on Colorado River water issues, I trotted out the Las Vegas example because the issue The Economist keyed in on is so interesting to me. Vegas looks crazy water wasteful. But the underlying numbers are actually kind of encouraging. Vegas water use and population data is another example of the “decoupling” I’ve been writing about – water use dropping even as population, economic growth, ag productivity, etc., rise. Here’s some of the data I’ve assembled in research for my book, which shows the water use curve bending down, significantly, after 2002, even as population has continued to grow:

Vegas and Candide

A colleague who’s been helping me think about these issues has been properly cautioning me against Panglossian optimism. (In fact, this colleague literally bade me read Candide so I would understand the fallacy of my “Panglossian optimism”. It’s a short book, and the university library a two minute walk from my office offered a choice of translations. I love my new academic posting.) I sometimes get sloppy with my “when people have less water, they use less water” argument, as if the sort of adaptive capacity that happened in Las Vegas is inevitable. This is not, in fact, the best of all possible worlds, as Candide so painfully discovered. But neither is the sort of pessimism, the we’re-completely-doomed rhetoric around Western water management that makes a lot of our current water policy rhetoric sound like Candide’s downer of a traveling companion Martin. (The scenes of Candide and Martin’s trip from South America back to Europe are like a hilarious pastiche of a journalist’s 2015 road trip through California’s Central Valley. “Why, then, was this world formed at all? asked Candide. To drive us mad, answered Martin.”)

These examples of adaptive capacity I’m trotting out, of “decoupling”, are a sign that solving our water problems is tractable, and that there are examples of how one might succeed. But it’s not inevitable. Lake Mead’s still kind of empty.

At the end of the book, Candide realizes that the important thing is to tend your garden.