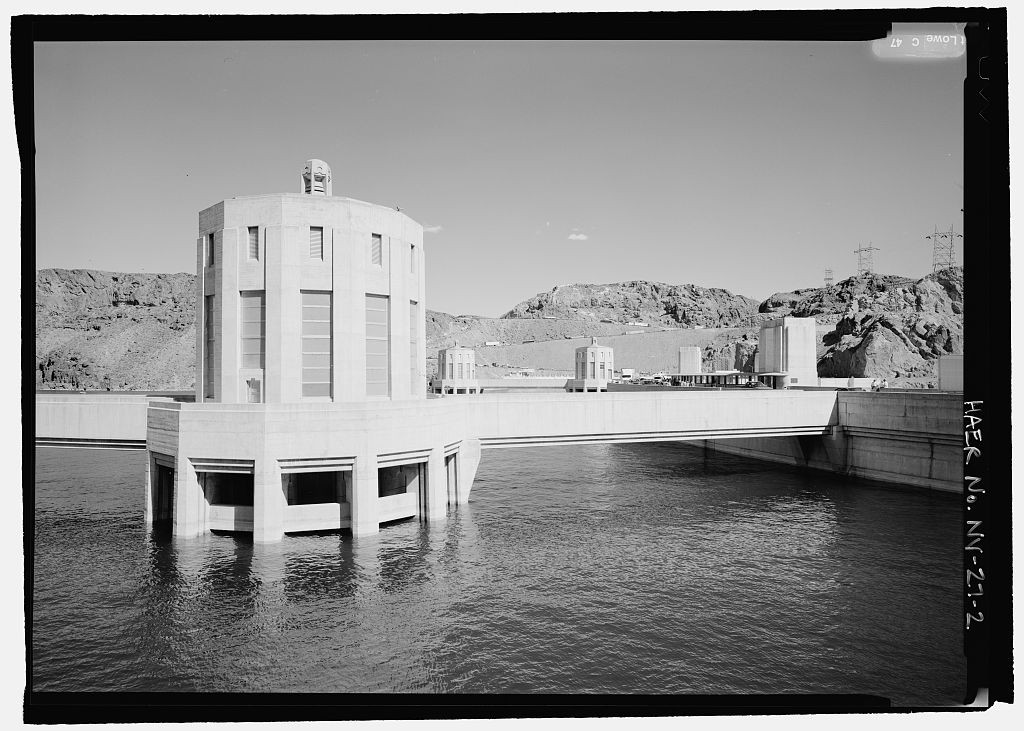

Hoover Dam, Lake Mead bathtub ring, February 23, 2015. Elevation 1088.97. © John Fleck

No Lower Colorado River shortage for now, but don’t break out the party hats.

Lake Mead is forecast to end calendar year 2015 with a surface elevation of 1,082.33 feet above sea level, according to new numbers released yesterday by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The current forecast for the end of 2016 is 1,079.57. The good news is that both of those numbers are greater than 1,075, which means the odds are against there being a “shortage” declared this year or next (when Mead hits 1,075 on some future January 1, rules kick in that reduce Arizona, Nevada, and Mexico allocations – repeat after me “this is not a crisis” – more here).

The bad news is that 1,079.57 is lower than 1,082.33, which means that even in these sorta good times, hydrologically speaking, Lake Mead keeps dropping. By “good times”, I mean that a big boost of precipitation in recent months in the Upper Colorado River Basin means that Lake Powell, the big reservoir at the upstream end of the Grand Canyon, is actually inching up right now. It’s forecast to end this year nearly five feet above last year’s levels, with the chance it could go up again next year. The good hydrology means that, under the river’s operating rules, Lake Powell will release “bonus” water this year and next. Under the rules, the Upper Basin is sorta legally required to release 8.23 million acre feet from Lake Powell down through the Grand Canyon to Lake Mead. This year and next, the current forecast calls for 9 million acre feet.

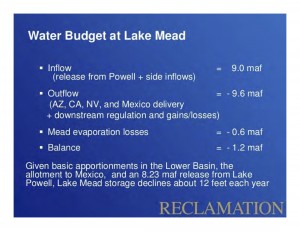

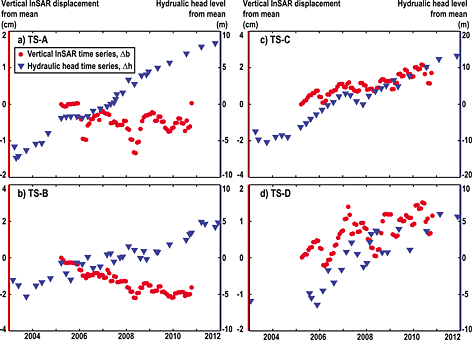

Lower Basin Water Budget, courtesy USBR

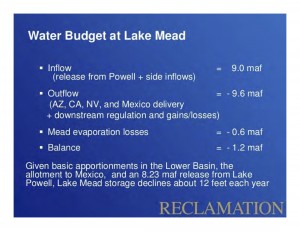

But despite that “bonus water”, the Bureau of Reclamation’s latest monthly water management planning report (the “24-month study”, pdf) shows Lake Mead is likely to just keep dropping.

How could that be?

The Lower Colorado “structural deficit”

Water managers call it the “structural deficit” – the hydrologic reality that under the current water allocation rules, there is more water allocated on paper flowing out of Lake Mead than can reliably be expected to flow into Lake Mead. The table describes what happens if Mead gets the legal minimum required, 8.23 million acre feet. With those levels of inflow, the “structural deficit” is 1.2 million acre feet per year. With the “bonus water” of a 9 million acre foot inflow from Lake Powell, the structural deficit shrinks to a few hundred thousand acre feet, give or take some math.

So to reiterate, even with a dollop of extra water flowing in, Lake Mead keeps dropping, as it will continue to do until the water management community comes up with a scheme to reduce allocations and consumption below current levels. As I said above, this is not a crisis. But neither is it a good thing.

I know, I know, y’all are working on it. I’ll quit nagging.