The book’s going well, thanks for asking. See below.

What motivates me

In my new gig as a university lecturer, my colleague and co-teacher Bob Berrens has the gray old faculty members (there are three of us) talk to the students on the opening day of class about what motivates us. It is the first in a series of courses in the University of New Mexico’s Water Resources Program that, when combined with more technical work scattered across campus (hydrology, engineering, earth science, computer modeling and simulation, public policy, and the like) we hope will provide a foundation for these young people to go forth in the world and fix the messes our generation and those who came before us have created.

Here is the story I tell.

Pumping groundwater on the limotrophe: citrus farming on the U.S.-Mexico border between Yuma and San Luis, March 2014, by John Fleck

Whenever I go to a place, I invariably end up going down to the water. As humans, we drape our communities around the water, building cities at the point where the river can be crossed, or where we can draw water to drink and irrigate our crops, or flush our waste water back into the river to be carried away. For much of humanity’s history, boats were the most important means of transportation, so we clustered around the ocean, ports, and navigable rivers. And then, as we do, we outgrew those early decisions, with sometimes indelicate results. London’s “great stink” of the summer of 1858 showed the limitations of the Thames as a place to dump the growing city’s shit. San Luis Río Colorado, on the Arizona-Sonora border, shows what happens when we run a river dry. Outside Kettleman City in California, almond farmers are pumping so much water that the ground is sinking.

If you look at the water long enough, you can start to see, in the things that have grown up around it, a marvelously intricate set of feedback loops between the water and the people. In his book City Water, City Life , Carl Smith shows how our very notions of modern municipal governance and community in some sense grew out of the need to get clean water to city people, and safely carry away their shit.

, Carl Smith shows how our very notions of modern municipal governance and community in some sense grew out of the need to get clean water to city people, and safely carry away their shit.

And so I go down to the water, because of my belief that we can always begin to understand the human geography and history of a place by starting with the water.

Getting down to the water

Seven months ago I left a thirty year career as a newspaper journalist to write this book thing y’all keep hearing me yammer about. I’ve been working on it off and on for years, but I realized last December that the only way I could do it right was to remodel my life in such a way that Writing a Book was my only job.

Colorado River flowing beneath the I-10 bridge at Blythe, February 2015

And thus I found myself in the fading light of a February afternoon, after devouring a fast food burger and checking into a cheap motel in Blythe, California, driving east out of town to find my way down to the Colorado River.

This is metaphor, and a clumsy one. I literally have spent many years trying to get down to the water of the Colorado River – beneath the old railroad bridge in Yuma, on the rapids of the Grand Canyon, along the waterskiing mecca of Parker, beside the canals of Phoenix, in the farm fields of Wellton Mohawk, at the intakes of the San Juan-Chama Drinking Water Project here in my home town of Albuquerque. You see in my list the fundamental conceit of my notion of “the water” – the Colorado River as human construct. Fradkin was right when he called it a “a river no more” , if you grant his meaning of “river”. Fradkin, like me, put into the Colorado River at Blythe in a canoe. I called it “little more than a slow-moving lake”. Fradkin had harsher words. But viewed expansively, the Colorado River is a vast human construct today, as much about taking water out of the old river channel and doing new things with it, and for me “getting down to the water” requires embracing and trying to understand it in that way.

, if you grant his meaning of “river”. Fradkin, like me, put into the Colorado River at Blythe in a canoe. I called it “little more than a slow-moving lake”. Fradkin had harsher words. But viewed expansively, the Colorado River is a vast human construct today, as much about taking water out of the old river channel and doing new things with it, and for me “getting down to the water” requires embracing and trying to understand it in that way.

The last seven months have been a glorious opportunity to “get down to the water”, both literally in the chance to visit my beloved Colorado River in all its messy glory, and also metaphorically in the chance to talk to smart people and read more deeply than I ever had the chance to as I tried to digest and then share knowledge one newspaper story at a time. I’ve never had so much fun in my life, which is a high bar. I pride myself on being very good at having fun.

Blah, blah, blah, but how’s the book going?

Palo Verde Irrigation District canal, of Blythe, by John Fleck

The occasion for all this self-indulgent thumb sucking is a milestone today, completion of the first draft of my book, Beyond the Water Wars. I’m a day early in hitting a self-imposed deadline. The manuscript’s not due until the end of the year, but I set myself this deadline – draft by the end of August – to give myself lots of time to clean things up. I met the milestone in part by cutting myself some serious slack – my definition of “completion” and “first draft” are loose. There are holes left that require more reporting, research, and thought, but they’re now clearly constrained. There’s a lot of muddy thinking yet to be clarified. And a lot of what I’m written bears some resemblance to the Thames of 1858, if you know what I mean.

But I can finally see the whole thing.

Writing a book turns out to be harder than I thought, because of the way my understanding has deepened and shifted as I worked. It is especially hard because one of my central premises, what I’ve called the “no one’s in charge-ness” of the Colorado River and the West’s water management, does not lend itself to narrative. The properties of emergence in complex adaptive systems, of which this is one, lack storylines in the same way that hierarchies and linear dynamics do. William Blomquist, in his superb (and frustratingly hard-to-find – thank you UNM interlibrary loan!) work on Southern California water management Dividing the Waters , bids us look closely as we think about contemporary water management at the question of whether we are seeing “diverse order” or merely chaos.

, bids us look closely as we think about contemporary water management at the question of whether we are seeing “diverse order” or merely chaos.

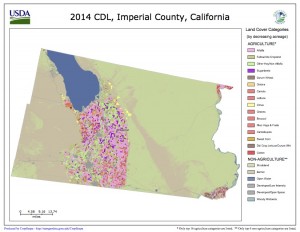

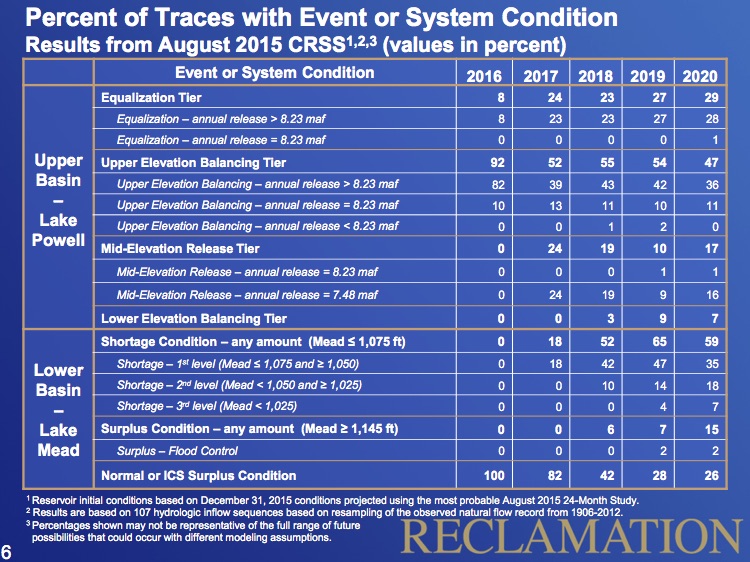

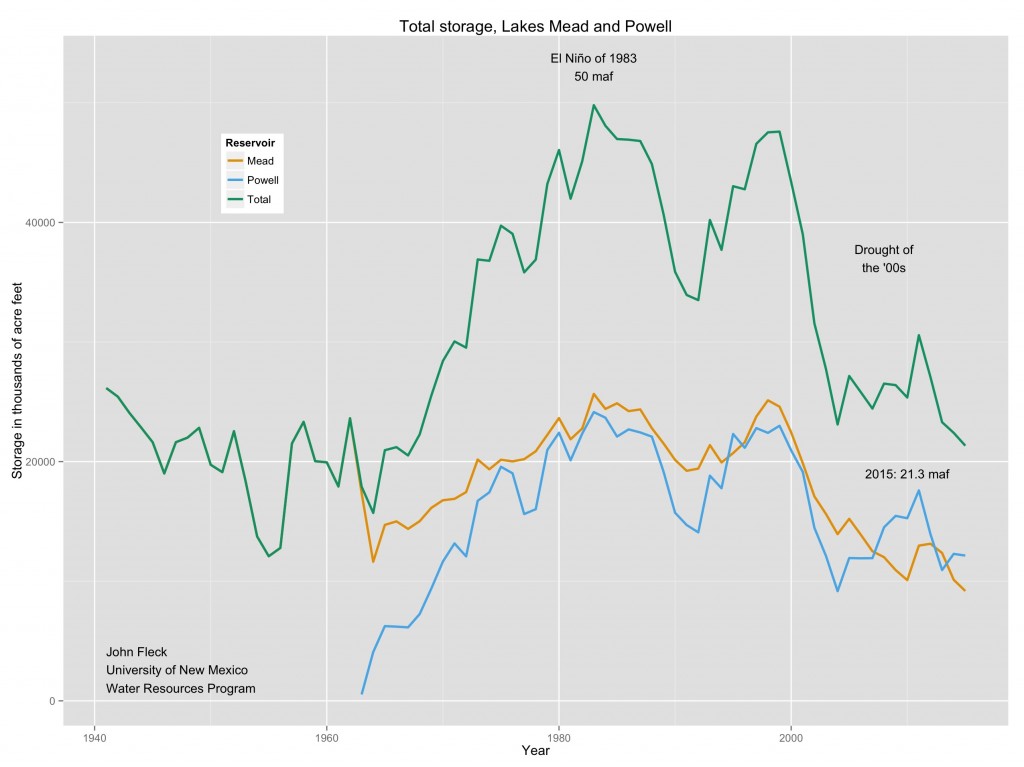

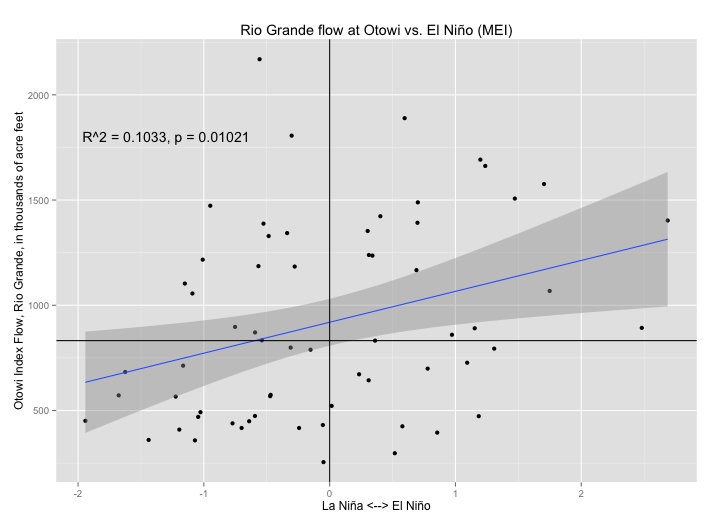

My book’s central premise draws on the definition of “resilience” I learned from my UNM colleague Melinda Harm Benson: the ability of a system to absorb a shock while retaining its basic structure and function. Here, this means the communities that have draped themselves around the Colorado River, and it poses a central dilemma. If the risk is that we have built too much of everything – too much Phoenix, Las Vegas, and Albuquerque, too much Imperial, Maricopa County, and Yuma agriculture – for the water available, how might we retain those basic structures under the shock of drought and climate change and, therefore, less water?

As it slowly emerges from the muck, my book makes a narrative argument for “diverse order”, an adaptive capacity found in the messy, flexible governance that will allow us to get by on less water, and share. Wallace Stegner said it better:

said it better:

One cannot be pessimistic about the West. This is the native home of hope. When it fully learns that cooperation, not rugged individualism, is the quality that most characterizes and preserves it, then it will have achieved itself and outlived its origins. Then it has a chance to create a society to match its scenery.

It’s also telling stories about the river in its many forms. As the sage of the Lower Colorado once said, “We all have our stories about the river.”