It's time to stop calling them wastewater treatment plants. Henceforth they shall be known as #water recovery plants

— Peter Gleick (@PeterGleick) September 23, 2015

Met eyeing sewage recycling for Southern California supply

Southern California water policy is looking like a game of speed chess right now. Amid the moves to supplement its Colorado River flow with extra water from Las Vegas and Imperial (agenda pdf), Met’s board also is considering spending money on cleaning up and reusing more of the sewage effluent Southern California currently dumps in the ocean. Here’s Matt Stevens’ take:

The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California is in talks with Los Angeles County sanitation districts about developing what could be one of the largest recycled water programs in the world.

In a committee meeting Monday, the agency’s staff presented the framework of a plan to purify and reuse as much as 168,000 acre-feet of water a year – enough to serve about twice that number of households for a year.

Doing so would require MWD to build a treatment plant and delivery facilities and comply with various environmental regulations. Officials say similar projects have cost about $1 billion.

Sewage recycling a shift?

Stevens and one of the board members he quotes call this a shift away from water importation for Met, but I’d argue that shift has been underway for nearly 20 years, since the development of Met’s “Integrated Resources Plan” in the mid-1990s. It was the IRP’s emphasis on more reuse, conjunctive groundwater management, and similar measures that positioned Met to successfully cope with the 2003 Department of the Interior decision to slash the agency’s Colorado River Aqueduct supplies. (Buy my book! As soon as I finish writing it! I’m almost done!)

But Southern California still dumps a lot of treated effluent into the ocean, so this option still leaves the region more room yet to move on the recycling front.

That time Lawrence Ferlinghetti visited the Salton Sea

From the Paris Review, poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s journal of his 1961 visit to El Centro and the Salton Sea:

Even at the Salton Sea, the face of death has its smile. In the morning the wind is still blowing but the sun is bright, and life is stirring. Even at the bottom of a well, there’s life.

He took a bus, and seems to have left as quickly as he could, headed for San Diego. It does not sound as though he enjoyed San Diego either.

Fleck’s water news, Vegas edition

I broke the first rule of something or another by reading the comments on this week’s Las Vegas water news stories. Yowza. More in my latest water newsletter.

As always, you can subscribe to the newsletter here.

Western Colorado has some pretty

Despite drought, California farm employment rising

I sometimes think that, in trying to understand the impacts of drought, we pay too much attention to the water numbers. It’s not that it doesn’t matter how much is in the reservoir, or is being pumped from the ground, but it’s only the first link in the chain of impacts.

California economist Jeff Michael points us to the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, which provides a relatively reliable and quick measure of employment impacts in the agricultural sectors, which is one area we would expect to see a societal response to drought. Here’s Jeff’s latest on the data, showing continued employment growth in California farm sector in spite of four years of horrendous drought:

For a number of years, the largest growth in farm jobs has been in the winter months rather than the peak summer months. It suggests there is some restructuring going on in the seasonal patterns of the labor market, probably caused by the increasing number of permanent crops. It could also reflect a tighter labor market which makes employers (in all industries) less willing to layoff workers during slack times.

What adaptive capacity looks like.

El Niño/Colorado River Basin update

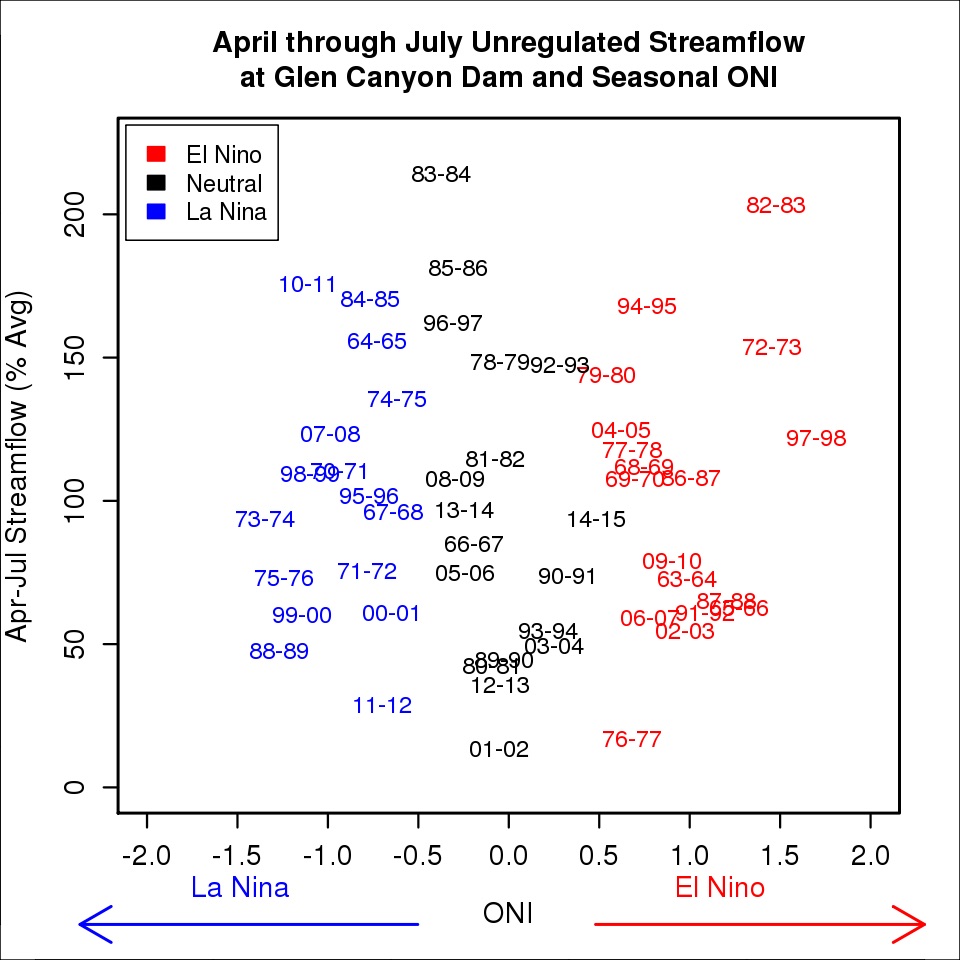

Since I wrote last month about the impact (or lack of impact) of El Niño on Colorado River flows, Paul Miller at the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center has done a new, more detailed analysis than the one I showed (which I had attributed to the Central Arizona Project folks, but which originally came from CBRFC):

The basic message is the same: the three strongest El Niño years have been wet, but that’s such a small statistical sample, and when you expand the universe to all El Niño years (the red ones on the graph above) you can see all kinds of scatter and pretty much zero statistical significance.

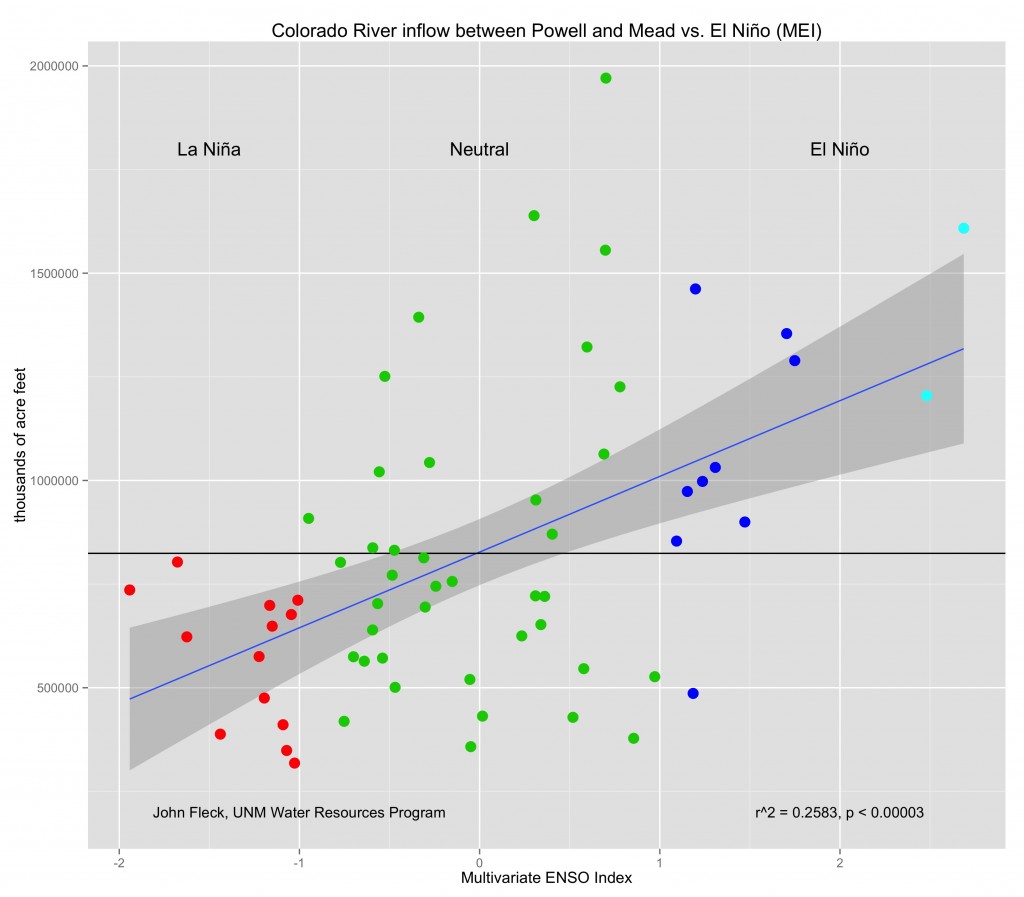

This is flow measured at Lee’s Ferry, the dividing line between the Upper Basin and the Lower Basin for purpose of Colorado River Compact administration. But Paul’s data got me curious. What about downstream of that point? Lee’s Ferry is the most important measurement point on the river, and the standard for this sort of thing. But flows below that point also are interesting, because the inflows downstream from Lee’s Ferry – especially the Virgin River and Little Colorado – are essentially “free water” for the Lower Basin when they are high and problem when they are low. And, in fact, El Niño years do show higher flows on this stretch of the river (warning: journalist doing his own math):

This makes sense. The impact of El Niño is weaker as you go north, into the main part of the basin. But in the lower basin, especially Arizona, El Niño does tend to be wetter to the tune of about 170,000 acre feet per year compared to the long term average for the period I looked at. I only calculated flows between Lee’s Ferry and Lake Mead, but river management folks say they also expect this downstream from Lake Mead, especially on the Bill Williams River. On average, this is enough to add a foot or two to Lake Mead during El Niño years. Not enough to make El Niño a drought mitigation tool, but a bit of potential good news for the Lower Basin.

(Note on data sources: El Niño comes from Klaus Wolter’s Multivariate ENSO Index, Colorado River flows from the USBR’s natural flow dataset. Period calculated: 1950-2012, because that’s the period for which the two datasets overlap.)

A promising seasonal forecast for the Colorado River Basin

The federal Climate Prediction Center’s seasonal forecast, out this morning, looks promising for the Colorado River Basin:

These forecast maps can be visually deceptive. The greens mean a shift of odds toward wetter weather, not a forecast that we should expect wetter weather. Dice, loaded slightly in our favor. You can see all the precip maps here, which are showing odds tipped toward wet well into the spring across most of the basin, with especially strong odds of wetter weather in the southern part of the basin.

Just beware the risk (reality?) of warmer temperatures, which pose the risk of sapping river flows once the water hits the ground.

Cynthia Barnett’s “Rain” a National Book Award finalist

So excited for my friend Cynthia Barnett, whose book Rain: A Natural and Cultural History is a nonfiction finalist for the National Book Award (pdf). It’s a great book. You should read it.

Las Vegas to help out Southern California with 150,000 acre feet of Colorado River water

The Southern Nevada Water Authority’s board will take up a proposal this Thursday to ship 150,000 acre feet of Las Vegas’s unused Colorado River water to Southern California to help out during California’s epic drought.

The water will help the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California make up for shortfalls in its supplies from Northern California, where drought has dramatically reduced the amount of water available for shipment through California’s State Water Project. Met is basically desperate, and Las Vegas has been so successful at water conservation that it is only using 75 percent of its Colorado River allocation these days.

If I was trying to explain this in the simplest possible terms, I would put it this way: Las Vegas is selling L.A. and San Diego 150,000 acre feet of water at a price tag of $295.83 cents per acre foot. But language here matters, so let’s be careful about the legal terminology. It would be wrong to call this a “sale” of water. More like a loan, or a banking agreement? The agreement between SNWA and MWD calls for Met to pay Vegas $44.375 million, and Vegas in turn will “store” 150,000 acre feet of water in Met’s system, that might be paid back (water and money) some day maybe sorta. But “store” really means Met can just use it to meet drought needs now.

Storage and Interstate Release Agreement

This is made possible by a “Storage and Interstate Release Agreement“, which provides the states of the Lower Colorado River Basin the flexibility to do water deals across state lines without calling them water transfers. Met and Southern Nevada have had such an agreement in place since 2004, and Southern Nevada already has 205,225 acre feet of water “stored” in Met’s system. (Nevada has another 601,041 acre feet stored in Arizona.)

Matt Jenkins in his High Country News profile of Pat Mulroy earlier this year had a great bit of business explaining the linguistic care with which these deals must be handled:

[T]ransfers, even within the Lower Basin, are … politically charged. “Don’t ever call it a transfer,” (Mulroy) scolded during a 2008 interview. “It’s a banking agreement. That thing will disappear on us tomorrow if we call it a transfer.”

So this is definitely not a transfer. If and when Las Vegas needs the water back, it’ll pay Met “a proportional amount of its costs” and grab the water from Lake Mead via an accounting swap. (It’s not like it makes sense to literally pump the water back uphill from Diamond Valley Lake to Vegas.) So maybe this is more like a “loan” of water?

Whatever we call it, it’s an important example of the sort of adaptive capacity Colorado River water managers have been developing in recent years to overcome the legal strictures that tie up water management flexibility under the cumbersome Law of the River.