Sen. Jeff Flake, R-Ariz., had a go at Deputy Interior Secretary Mike Connor during a Senate hearing last week, looking for assurances that if his state left unused water in Lake Mead as part of a Colorado River Basin conservation effort, the Interior Department wouldn’t just kype it and give it to someone else (mumble mumble California something mumble mumble):

The number one priority in Arizona is to make sure that when Arizona, or any other state, voluntarily contributes their water to the health of the Colorado system the contributed water actually stays in the system and doesn’t disappear along somebody else’s canals.

“system water” behind Hoover Dam – the “paracommons”, wet water style

This is the latest manifestation of something I’ve written about before, Arizona’s deep-seated paranoia that others (mumble mumble California something mumble mumble) have designs on their scarce water supplies. But it also gets to a really interesting issue that I think needs to be articulated carefully as we go about the project of using less water: where does conserved water go?

Bruce Lankford of the University of East Anglia, in his recent book Resource Efficiency Complexity and the Commons: The Paracommons and Paradoxes of Natural Resource Losses, Wastes and Wastages , coins a new term to try to get his arms around the issue – paracommons:

, coins a new term to try to get his arms around the issue – paracommons:

In a scarce world, society is increasingly interested in the efficiency of resource use; how to get more from less. Yet if you ‘save’ a resource, what does that mean and who gets the ‘saved’ resource? In other words who gets the gain of an efficiency gain?

Consider a few examples:

Las Vegas

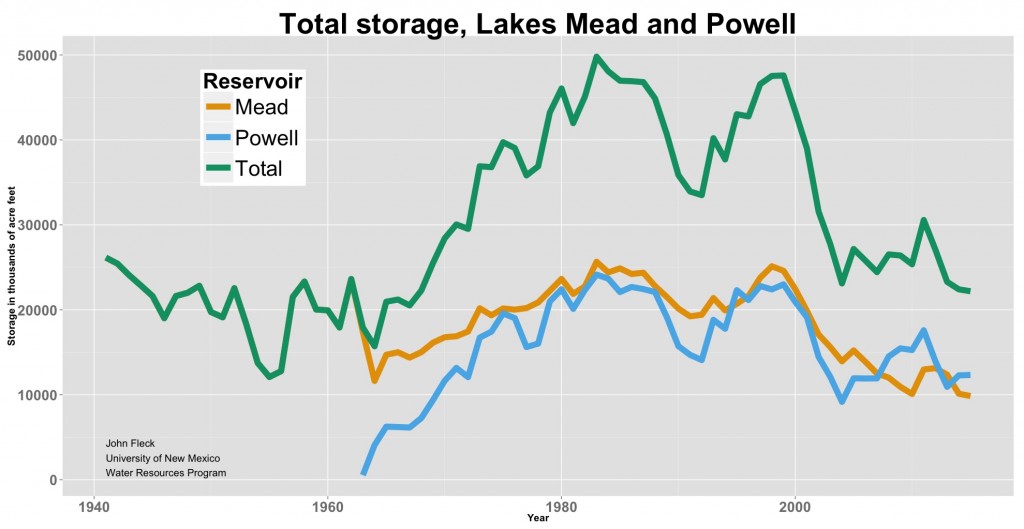

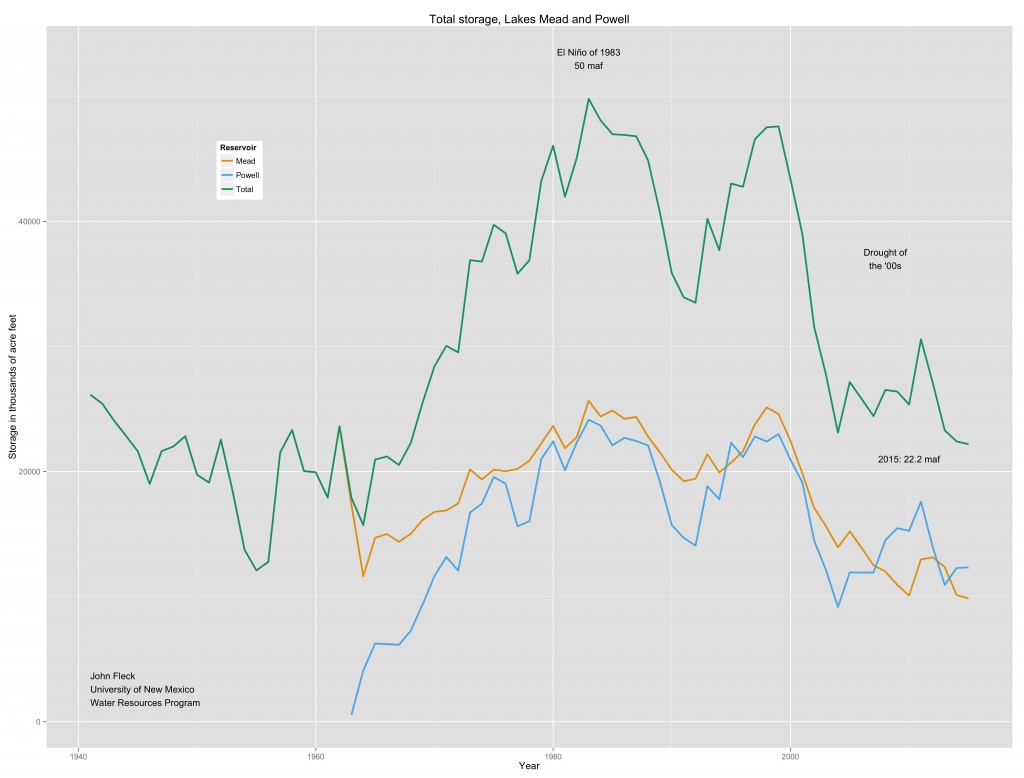

As a result of its extraordinary water conservation success, Las Vegas reduced its use of Colorado River water by more than 30 percent over the last decade. That saved water remains Las Vegas’s. It has banked lots of water in aquifers around the West with the idea that it could withdraw that water for its own later use.

Phoenix

Phoenix also is not using its full Colorado River allocation, but the rules around its Colorado River water use are different. Any “saved” Colorado River water that might result from Phoenix’s conservation efforts reverts to other users. (see here and here for an explanation of the rules)

Yuma

red lettuce, Yuma County Arizona

Farmers in Yuma County (they’re the ones growing a big fraction of your lettuce in the winter) have reduced their water use by more than 30 percent in the last three decades as they have shifted to more efficient irrigation techniques. Like Phoenix, they have seen their water revert to other Arizona water users who are behind them in that state’s water allocation queue. They haven’t gotten a dime for the water.

Imperial

Farmers in the Imperial Valley of southeastern California have reduced their water use by 22 percent in the last decade. They have been compensated for this by other water users in California, with saved water going to Coachella Valley, San Diego, and the Los Angeles area. Some of the saved water is providing environmental flows to the Salton Sea.

Mexico

System improvements and operational changes in Mexico in recent years have saved water for a variety of reasons and purposes. Some of that water was used last year for an environmental pulse flow through the desiccated Colorado River Delta.

the paracommons

So we’ve got four different types of cases above:

- conserved water retained by the entity doing the conserving for later use

- conserved water going into the common pool for use by others

- one group of water users paying for the water conserved by another

- conserved water used for environmental benefit

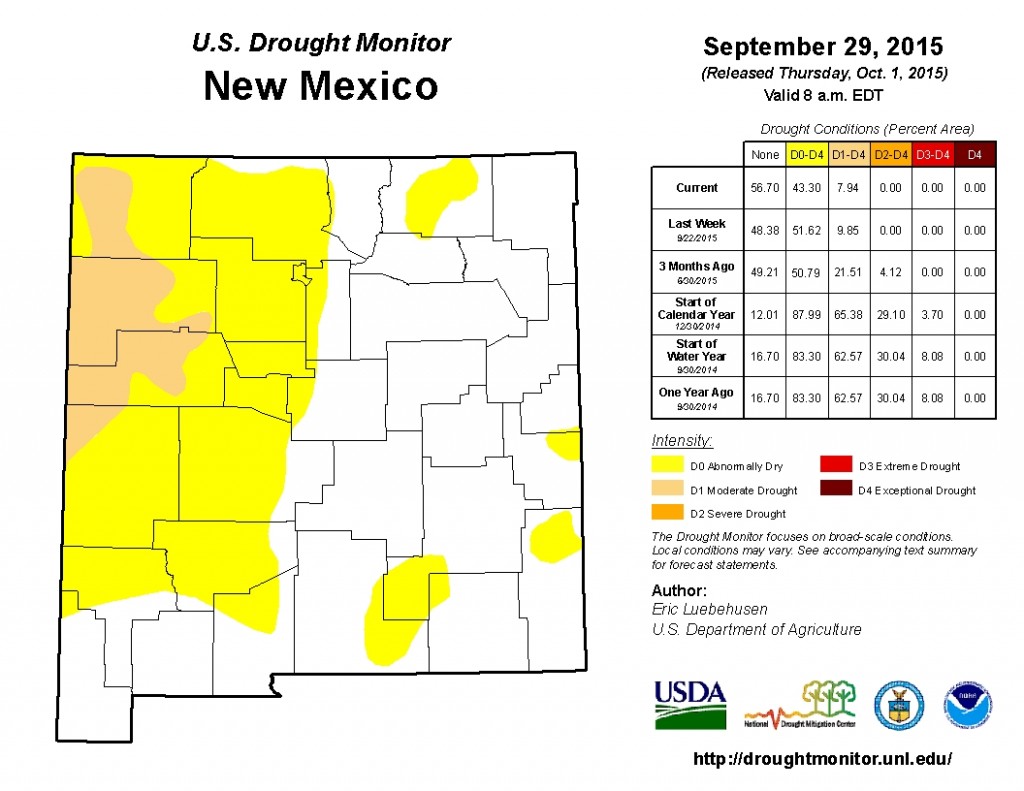

The differences in the above cases illustrate the range of rules governing water management. The rules are crazy complicated, and importantly they generally weren’t written with this sort of “How can we best manage conserved water?” question in mind.

I hate the word “paracommons”, but Lankford is careful and deliberate in defending the need to coin a new word to deal with a resource category that, because it is poorly labeled, also has been poorly conceptualized. And strange word or not, as a conceptual category I find the paracommons quite useful. Lankford’s basic argument is essentially that efficiency yields something (in this case saved water) that has a lot of the basic characteristics of a common pool resource. Do we leave that water in the river to reduce the environmental damage our diversions have caused? Do we save it in a reservoir for future use? Do we just hand it off to another water user who’s come up short this year? This raises a whole bunch of institutional challenges that we’re only beginning to grapple with as we transition from water management under surplus to scarcity.

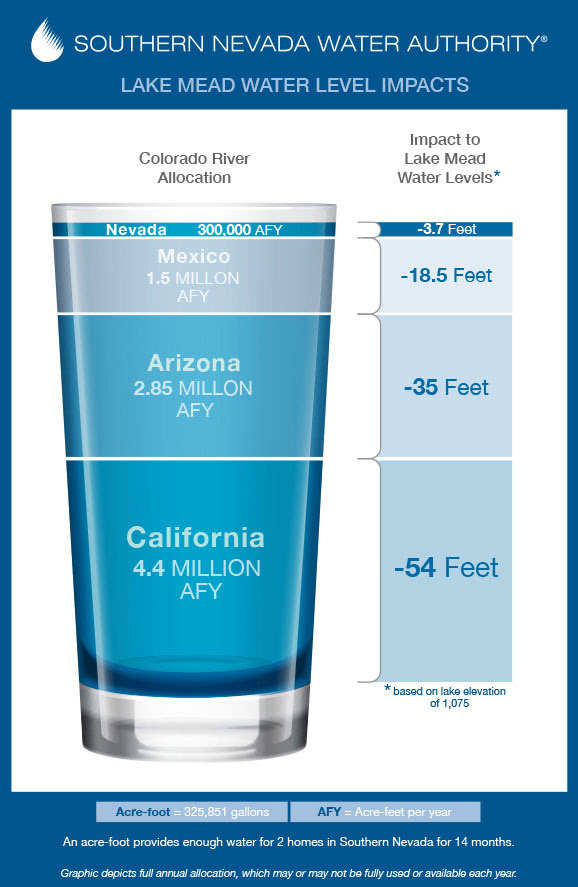

Flake’s grandstanding in the Senate hearing was annoying (can you Grand Canyon staters chill already about the “California’s gonna steal our water” meme? increasingly sounding to me like fingers on a blackboard). But his political play to the home crowd is enabled by confusion on this issue. The water in question is what Colorado River Basin managers are calling “system water”, by which they mean water that is intentionally conserved and just left in the common pool, with no one’s name attached and no purpose delineated for its use. All the cool kids are trying to pull off system conservation deals right now as a way of reducing the decline in Lake Mead (see here and here). Ambiguity about the status of that saved water as it enters the common pool is exactly the problem Lankford is writing about. And it is precisely that ambiguity that leaves the door open for Arizona’s old fears that someone’s trying to screw them in a water deal.