Albuquerque yesterday (Oct. 15) began pumping groundwater from an aquifer in the city’s northeast heights, the first time aquifer storage and recovery in New Mexico has reached the “recovery” phase.

New Mexico is late to this party – states around us have been doing this for years. But it’s a huge milestone in water management here.

Bear Canyon recharge, courtesy ABCWUA

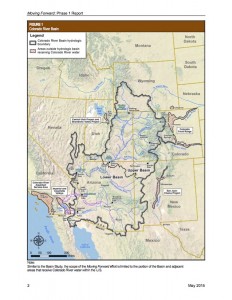

This started, I think, back in 2008 with water recharged into Bear Canyon Arroyo, a sand-and-gravel-bottomed natural arroyo that flows down alongside the Arroyo del Oso Golf Course in the midst of suburban Albuquerque. The water comes from the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority’s allocation of San Juan-Chama Project water, imported from the Colorado River Basin. In a pilot phase over a number of years, the Water Authority stored 1,073 acre feet of water, which is what is now being pumped out over the next month, according to Katherine Yuhas, who’s overseeing the project for the agency.

The pumping will be done over the next month from six wells in the area around Bear Canyon, drawing on the same area of the aquifer that has been recharged.

The experiment here is as much institutional as it is hydrologic – how do you handle the accounting, making sure the water really got to the aquifer and doing the accounting as the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority recovers it? I can’t emphasize the importance of this piece enough – it’s something we talk about a lot in the intro to contemporary issues class I’m helping teach for University of New Mexico water resources grad students. Water management is half hydrology, half law, and half institutions. (I’m primarily on the law and policy side, not super good at math, but I think I’ve got the ratios roughly right.) So you not only need to figure out the physical part of getting the water into the ground and measuring that it got where you sent it. You also have to deal with the legal and institutional part – getting the Office of State Engineer to accept your measurements, agree with how the accounting is done when you pull the water out, etc.

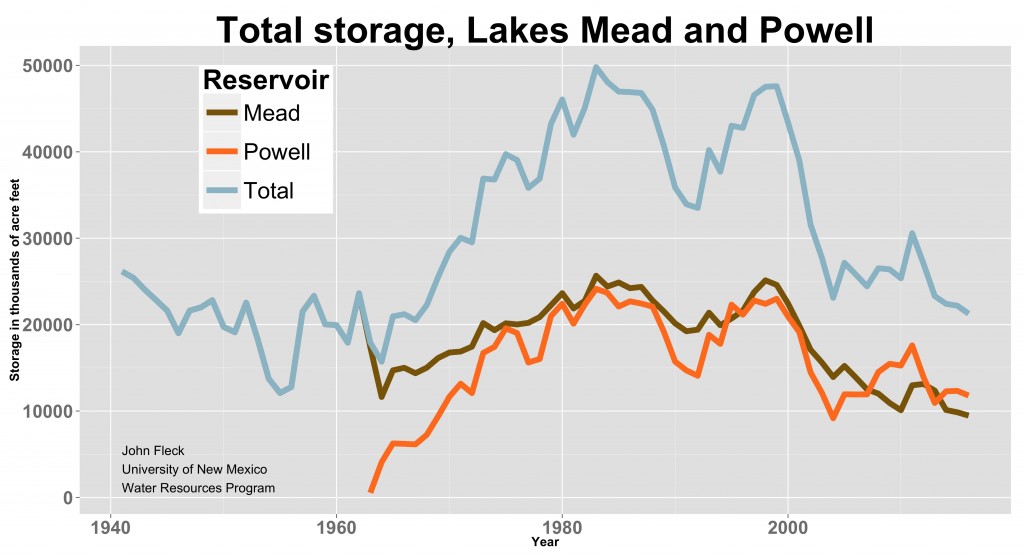

Aquifer storage and recovery allows managers to smooth out variability, putting water in the ground on the wet side of the variability curve and pulling it out on the dry side. In Albuquerque, this would provide flexibility to manage San Juan-Chama water, which is imported across the continental divide from the upper headwaters of the San Juan River, in the Colorado River Basin.

This is an area in which New Mexico water management is staggeringly far behind other states. William Blomquist, in his classic collection of Southern California groundwater management case studies Dividing the Waters , describes simple recharge operations in Pasadena’s Arroyo Seco carried out during the drought of 1895-1904. Recharge of various sorts – storm water, imported Colorado River water, treated sewage effluent – has been done in Southern California ever since. One of the critical insights in Blomquist’s book is the importance of getting the institutional pieces right.

, describes simple recharge operations in Pasadena’s Arroyo Seco carried out during the drought of 1895-1904. Recharge of various sorts – storm water, imported Colorado River water, treated sewage effluent – has been done in Southern California ever since. One of the critical insights in Blomquist’s book is the importance of getting the institutional pieces right.

In Arizona, groundwater banking of surplus Colorado River water has been standard operating procedure for decades, with 3.965 million acre feet banked as of the end of 2014 (pdf). So Albuquerque’s 1,073 acre feet is small stuff. But it’s an important start.