With fall semester over yesterday, I called “faculty prerogative” and went out with Lissa for a weekday afternoon walk by the Rio Grande. I’m just an adjunct, but I’m trying to model the behaviors of my more distinguished university colleagues, and one of them is the rhythm of the academic calendar. Finals week is still underway, and the real faculty members still have to deal with grading and the bureaucracy of the end of the semester, but I’m just an adjunct, right? So my semester’s over. A walk by the river it was.

Rio Grande water flowing through Albuquerque, on its way to Texas, Dec. 9, 2015, by John Fleck

The grad students in our Water Resources Program “Contemporary Issues” class, the introduction to their masters degree curriculum, gave their final project presentations yesterday afternoon, and I couldn’t have been more pleased. One group studied New Mexico’s state and regional water planning process, one worked on direct potable reuse (“Don’t call it ‘toilet to tap’!”), and one reviewed the institutional framework in New Mexico for instream flows, as compared to other western states. All three groups showed me things I didn’t already know, and all three really wrestled with the deep difficulties of the water management problems they were studying.

Water management is hard.

The Rio Grande was booming today (at least relatively speaking – it’s a desert river), and it’s worth pondering why, in the context of what our students have been thinking about over the semester. Our curriculum puts a lot of emphasis on institutions, those formal and informal rule systems that govern the allocation, distribution, and management of our water. There’s a plain language meaning of the word that’s narrow, where “institution” == “government agency”. But one of the critical points we work on in class is understanding institutions more broadly, as the set of rules, both formal and informal, that govern repeated interactions among people. Government agencies are a piece of this, but it’s really the rules (and critically, both formal and informal, the guiding norms) that matter.

The rules that govern flow in the Rio Grande are complex and interlocking but one of the most important is the Rio Grande Compact, a contract among the three U.S. states that share the river (and the federal government – the feds are always part of compacts). The most important rules right now, as the Rio Grande flows through Albuquerque this warm December, involve the calendar. The compact sets out how much water New Mexico can use as the river flows through the state, and how much must be passed on to Texas. The accounting is done on a calendar year basis. So at the end of December, everyone’s gotta try to make the books balance.

Source: USGS

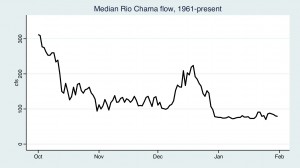

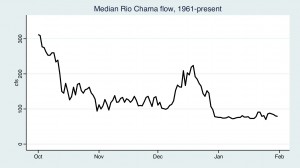

The implications for river flow through Albuquerque are fascinating. One of the basic tools of water management is the “hydrograph”, a graph of water flow relative to time. I’ve plotted up the winter hydrograph of median daily flow on the Rio Chama below Abiquiu Dam, the main regulatory structure upstream of Albuquerque. Every year in October, as the irrigation season winds down, releases from the dam steadily drop. And then in December, they tend to rise again for a few weeks. What’s up with that? There’s no phenomenon in the weather than might explain it, is there? December rainstorms?

No. It’s accounting. Frequently at this time of year, water that had been held in storage is moved downstream through Albuquerque and into Elephant Butte Reservoir, which is essentially the Texas compact bank account. It’s an accounting transfer, to make the books balance by the end of December.

One could imagine different sorts of institutional arrangements that might find advantages to moving that water at a different time of year. Perhaps (just speaking hypothetically) one might find advantage to moving it in the spring, for example, when additional water to support spring spawning of an endangered fish of some sort might be of value. But the institutions are what they are, and the calendar is what it is, and the water’s moving now. Check it out, it’s really nice down by our river right now.

You see these “institutional hydrographs” all over. My favorite is the Grand Canyon, where the Colorado River rises and falls in a diurnal cycle that’s linked to the use of Glen Canyon Dam to generate peaking power during times of high electricity demand. Big dams are great for that.

This year the Rio Grande accountants are unusually busy, with a lot more water flowing through Albuquerque than usual and a lot more interesting accounting. The institutional stuff gets complicated in a hurry. Right now there are three different accounting systems being balanced with a lot of water moving as a result. But the thing to watch is that January dropoff. If you’re in Albuquerque and enjoy a bit of water in your river, check it out now. The accountants should have their books balanced by the end of December, and the river will settle back into the quiet of winter.