Will we empty Lake Mead?

Which uses more water, lettuce or bacon?

That and news from the Colorado River Water Users Association’s annual meeting in John Fleck’s water news.

And you can subscribe here.

Will we empty Lake Mead?

Which uses more water, lettuce or bacon?

That and news from the Colorado River Water Users Association’s annual meeting in John Fleck’s water news.

And you can subscribe here.

I’m not sure who came up with the “More Slices than Pie” title for the panel discussion I moderated Thursday at the annual meeting of the Colorado River Water Users Association, but it had a nice ring. A big thanks to Tom McCann from the Central Arizona Project for putting the panel together and inviting me to help out. Important audience, important messages about the risks if basin water managers can’t come to grips with the need to stop draining their reservoirs so quickly.

There’s some important signaling here. For a long time, this thing we have come to call the “structural deficit” – the reality that paper allocations on the river exceed actual water supply – was an elephant in the room. It’s not that the overallocation problem was ignored in official discussions. People both inside and outside the basin’s water management institutions have talked about this for years.

Doug Kenney, University of Colorado, December 2010

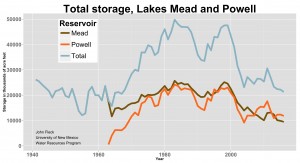

This image, for example, is from a 2010 presentation at CRWUA by the University of Colorado’s Doug Kenney pointing out that under normal water supply conditions (never mind drought or climate change) there is not enough water to keep Lake Mead from shrinking. In October of 2010, Lake Mead had dropped to historic lows, but then it got wet (Mead rose 46 feet in 2011) and the pressure was off.

There is a tension in the Colorado River management between the core group of managers operating at the basin scale who are trying to work out ways to deal with the overall shortfall, and water managers working at more local scales back home, who just want the water promised to them on paper by the deals negotiated back in the day. When it gets wet, as it did in the winter of 2010-11, it takes the pressure off of that conflict, because we can simply keep using water and sucking down the reservoirs rather than dealing with the shortfall.

But Mead is back to its record-setting lowest-it’s-been-since-it-filled ways. Thursday’s session putting the basin’s overallocation problem on the main stage at CRWUA for discussion by representatives of four of the major Colorado River Basin water agencies suggests that managing scarcity and risk rather than assuming abundance is, at least for now, the conventional narrative.

Caeser’s Palace, the annual meeting place of the Colorado River Water Users Association

CRWUA is a strange and wonderful thing, an annual gathering that brings all the disparate elements of the disaggregated Colorado River water management community – federal, state, local, farm, city, environmental, recreation – together in one spot. In a system in which no one is in charge, this ritualized annual coming together is critical for the social capital needed to deal with the basin’s tough issues. I wish I had the formal skills of an anthropologist or one of those people who studies formal and informal networks. CRWUA would make a great field study area.

There’s an odd turn of phrase that I’m increasingly hearing in the Colorado River management community in describing the risk of Lake Mead dropping in a hurry – “blowing through 1,020”. It’s an action verb, describing a reservoir in free fall if we don’t get bailed out by whatever the opposite of climate change and drought are. The problem is that as reservoir levels decline, the V-shaped profile of the big Colorado River reservoir means that there’s less water for a given amount of elevation, which means that we shift quickly from dropping five or ten or fifteen feet per year to plummeting from 1,020 to 895 in a hurry. When I started working on Colorado River issues, “895”, the level at which you can’t get water out of Lake Mead, didn’t get talked about much. But the number came up a lot at this year’s CRWUA.

Deputy Secretary of the Interior Mike Connor, in a talk yesterday, said the latest Bureau of Reclamation analyses put the risk of 1,020 in the next five years at somewhere between 11 and 30 percent. At those kinds of low reservoir levels, managing the system becomes far more difficult, and cuts needed to prevent the doomsday scenario are far more extreme.

The trick is for the basin leaders who understand this to craft a deal with the wisdom to make some water use reductions before 1,020 (or 1,030, or 1,040, or whatever) in a way that trades benefits of using that water now for a reduction in future risk.

The immediate problem now is in the Lower Basin, the states of Nevada, California, Arizona, Sonora, and Baja. The Upper Basin has its issues, involving how much water will be available to support future growth, but in the Lower Basin the question is how much water is available to support the farms and cities we’ve already got.

Lake Mead from the air, flying into Las Vegas

It’s pretty clear what a Lower Basin deal has to look like in general terms. It’s all about Arizona and California, which are by far the biggest users. Unless each state is willing to reduce its take on Lake Mead, it would be easy to blow through 1,020 in a hurry, as Connor’s numbers suggest. I’m confident (this is a lot of what my book is about) that both states have the capacity to continue to thrive on substantially less less water, both agriculture and cities, if we do it right. My forthcoming book spends a lot of time on what this adaptive capacity already looks like. But if Arizona and California don’t move soon and we blow through 1,020 with the resulting need for cuts that are deep and fast, my confidence about the grace with which we can adapt goes down.

Talks have been underway on this for a while, under the label “drought contingency planning”. (I hate that word – it’s not a drought! This is what normal looks like!) Connor and others suggested at CRWUA that agreement is near. There will be nuances to the deal, in terms of who takes how much reduction at what reservoir levels. The idea, as one of the senior federal officials explained, is a series of voluntary agreements (“At reservoir level X, we agree to take this much less water”) developed within the framework of the basin’s 2007 shortage sharing rules, but with larger reductions to slow the reservoir’s fall. The trick now will be for the negotiators to head back home and convince local water users that those paper water entitlements written into laws over the last hundred years are not real, and that for the health of the system they’ll have to adapt to the reality that there’s less water to go around.

This is the phase of the process I worry about most. There are tensions betweens states, and also among water users within states. Bad water politics back home (“Why are we giving up water just so Arizona/California/Phoenix/LA/Imperial/Yuma can have it!”) could scupper a deal. At that point, we could blow through 1,020 in a hurry.

CRWUA is a good place for that conversation to happen, because it’s a mix of both kinds of water managers – those who work at the basin scale, and those who have to deliver the water to farm gates and shower heads back home.

Anyone who flies in an airplane and doesn’t spend most of his time looking out the window wastes his money.

– Marc Reisner, Cadillac Desert

Lake Mead from the air, flying into Las Vegas

My Southwest flight into Las Vegas was nearly empty (a rarity these days), so I had my choice of window seats on either side of the plane and the chance to move back and forth. But the pilot’s descent into Las Vegas was literally directly over Hoover Dam, so we couldn’t see it.

Nice view of all the Lower Basin’s water in Lake Mead, though, just waiting for someone at the Bureau of Reclamation to turn the spigot and send it downstream to grow lettuce or water a golf course. Looks like plenty of water to me!

Ocotillo in the snow

It snowed overnight in Albuquerque.

Total water use in Albuquerque for the first 11 months of 2015 is down 6 percent from the same period in 2014, according to the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority’s latest pumping and diversions report. Indoor use (as measured indirectly by comparing this year’s sewage treatment plant outfall to last year’s) is essentially unchanged, suggesting that the bulk of the savings are in outdoor watering.

Since the sewage treatment outfall is being returned to the system for full use downstream (ecosystem, agriculture, downstream communities, and Rio Grande Compact deliveries to Texas), that means an estimated decrease in consumptive use (the outdoor use that really matters because the water cannot be returned to the system for reuse by others) is down a remarkable 13.5 percent.

Weather is clearly a factor here. Albuquerque precipitation is 15 percent above average for the calendar year. But also worth noting is that we have seen year after year of decrease, in both wet years and dry years, so community water users are doing something more complicated here than simply watering less when it’s raining.

Fortunately, the L.A. Department of Water and Power has come a long way in the last 20 years. For a time, says McQuilken, managers balked at the idea that conservation and recycling could replace the Mono Basin losses. But since then, the utility has become one of the country’s most progressive. Take water conservation. Simple measures like encouraging customers to rip out lawns and install low-flow toilets have made a stunning difference. Despite the addition of a million residents, Los Angeles uses less water today than it did nearly half a century ago. (emphasis added)

A paper out yesterday adds new detail to the picture provided by satellite groundwater observations of the Colorado River Basin, arguing that groundwater depletions from human pumping are not as large as suggested by previous research.

The paper, Hydrologic implications of GRACE satellite data in the Colorado River Basin published in Water Resources Research (behind paywall, sorry), points to large changes in soil moisture as a result of drought, rather than human groundwater pumping, as the explanation for a significant portion of water losses identified by NASA GRACE satellite observations. This is especially true in the Upper Colorado River Basin. In the Lower Basin, the picture is more complex, with some groundwater losses in parts of rural Arizona, balanced by stable or rising aquifers in the state’s heavily populated and heavily farmed central valleys.

The paper provides a significantly different picture than a widely publicized paper by Stephanie Castle, Jay Famiglietti and colleagues at UC Irvine and NASA last year that attributed the changes in water balance in the Colorado River Basin to unmanaged groundwater pumping by human water users.

The new analysis, from a team led by Bridget R. Scanlon at UT Austin and the USGS, uses new methodology for analyzing the GRACE satellite data in an attempt to better characterize the spatial detail of the missing water. GRACE, which infers changes in the mass of water above and below the earth’s surface by measuring changes in the gravitational tug on overflying satellites, has become a powerful tool for measuring groundwater depletion, especially in areas where the pumping is huge,

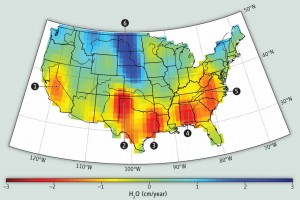

Data from the German-NASA GRACE satellites highlights groundwater depletion hotspots in the United States. CREDIT: CAROLINE DE LINAGE/UNIV. OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE, Science magazine

like California’s Central Valley and the Ogallala Aquifer in the U.S. midwest. But in areas where groundwater pumping is smaller, like the Colorado River Basin, the problem is trickier. GRACE provides an overall estimate of the change in the water mass balance, and then secondary calculations are needed to apportion how much of that change is groundwater, surface water, and the thin layer of soil moisture in between. Those secondary calculations introduce significant uncertainties into the results.

The Scanlon et al. paper is an attempt to resolve contradictions between the Castle et al. paper and work by other researchers. In particular, the new paper notes, the rates of depletion in the earlier paper were significantly larger in the Upper Basin than could be accounted for by known areas of groundwater pumping as identified by the U.S. Geological Survey’s exhaustive Water Use in the United States surveys. In the Lower Basin, the Castle et al. paper showed declines in groundwater levels at a time when analysis based on groundwater well data showed aquifers rising across a substantial part of the area in question.

Scanlon concluded that in the Colorado River’s Upper Basin, the loss of water identified by GRACE came in part from a reduction in reservoir storage, with the rest of the loss of water attributable to the natural loss of soil moisture that occurs across large areas during drought – not groundwater pumping.

In the lower basin, the new paper concludes that aquifer levels are stable or rising beneath the most populated parts of the state – the Phoenix-Tucson corridor – and that the groundwater losses seen by the satellite data are primarily in outlying areas where groundwater is less well regulated (something that is a hot topic of discussion in Arizona right now).

Some back story on why I was so interested in the new paper…. I was enthusiastic about the Castle paper when it came out, but when I went looking to “storyize” it for my book, it left me scratching my head. The original work was a groundbreaking attempt to apply the GRACE tools to the Colorado River Basin, but the data was too coarse to say where in the Basin the overpumping was happening. The paper argued that policy action was needed, but where? Beyond anecdotes, when I dug into the numbers looking for a way to tell a story that demonstrated the scale of overpumping the Castle paper argued was happening – enough farm acreage or municipal water use to match up with the groundwater use the Castle paper claimed – I was stumped. The numbers didn’t seem to pencil out, creating one of those “danger, journalist doing math!” moments I’m so prone to. I looked at USGS groundwater pumping data, and remote sensing data of ag acreage, and none of it added up. I’ve spent a lot of time in the last year trying to understand what can be said about who’s using water how and where in the Colorado River Basin, and I just couldn’t find where all this pumping could be. There literally weren’t enough farms and cities, especially in the upper basin, to account for the pumping the Castle paper said was happening. (“Danger, journalist doing math!”) I never ran across Scanlon or any of the authors of this new paper, but other scientists I talked to who work on groundwater and Colorado River Basin issues raised some of the same questions addressed in this new paper, describing methodological uncertainties could have led to an overstatement of the amount of groundwater being pumped. A paper by Bill Alley and Leonard Konikow discusses these methodological issues. One of my groundwater tutors, Michael Campana, (whose old University of New Mexico office I now occupy!) also raised questions early on. For my book, I just moved on, but I worried that the missing water was out there, and that I was just missing it. If that makes any sense. The Scanlon paper helped me sort out the discrepancy.

Sorry for the ramble, but this has been a nagging loose end. And a huge thanks to both groups of researchers. This is hard, cutting edge science, which is very relevant to water management policy.

Data source: USBR. 2016 projection based on USBR October 2015 24-Month Study

Preparing to moderate a panel at next week’s Colorado River Water Users Association annual meeting, I’m struck by the mix of good news and bad news on the river. 2015 water use across some major user groups is at record lows for the modern era, something that I don’t think gets enough attention. But Lake Mead keeps dropping.

As we near the end of 2015, this morning’s Bureau of Reclamation year end water forecast (source pdf) includes some encouraging numbers:

This clearly shows some significant “use less water” adaptive capacity in the system. And yet….

Total reservoir storage on the Colorado River system as of Monday was just 50 percent (source pdf). Lake Mead ended November with a surface elevation of 1,078.23 feet above sea level, the lowest for that date since it was filling in 1938.

This is the balancing act – a need for a recognition of the seriousness of the problem (Lake Mead keeps dropping!) while simultaneously also recognizing that significant progress has been made in using less water, and learning the lessons offered by that progress.

Let me know if you’re going to CRWUA, track me down, say “hi”.

Jon Christensen makes a great point:

Christensen says experts learned lessons about the “stickiness” of behaviour change during California’s drought.

“When there’s a lot of messaging about conserving water, when there are incentives to conserve water, people do conserve water, they use less water,” Christensen says.

“And when the drought is over there’s some rebound, but those conservation measures do tend to stick at the municipal level and at the household level. You learn new patterns and then those patterns can stick.”

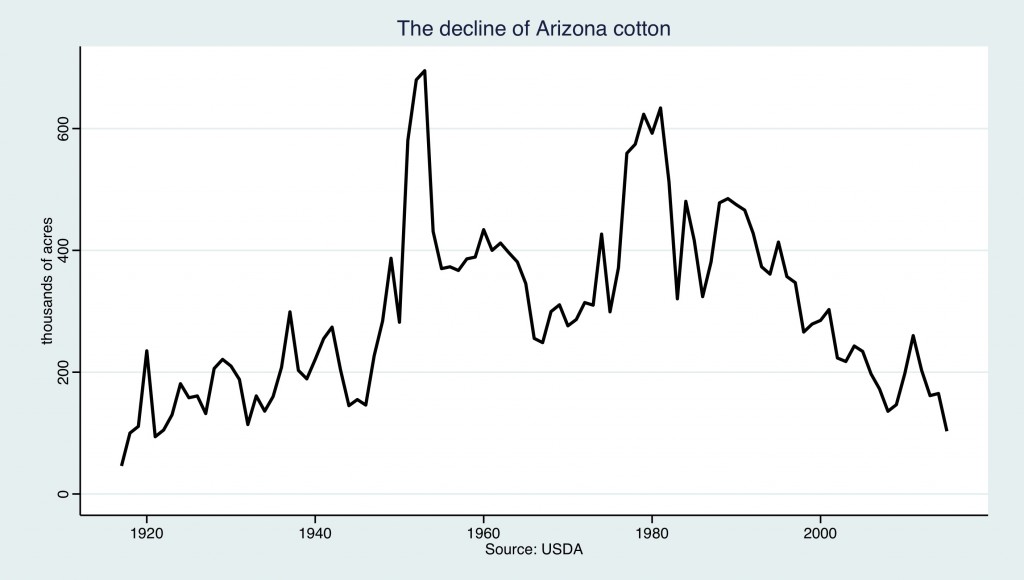

Arizona cotton acreage this year is the lowest it has been in nearly a century.

Cotton is incredibly important in the evolution of western water policy, in Arizona in particular and therefore in the Colorado River Basin in general. In Arizona, it was one of the “Three C’s” that dominated the state’s economy – cattle, copper, and cotton. The need for water to irrigate a cotton empire was foremost in the minds of state leaders when they asked the U.S. Supreme Court to intervene in Arizona’s dispute with California over Colorado River water. State leaders grasped earlier than most that their aquifers couldn’t sustain the 1950s-era groundwater pumping that was fueling the cotton boom.

In 1953, there was 695,000 acres of irrigated cotton in Arizona. In data released today by the USDA, that was down to 101,000 acres:

Arizona cotton

That is the lowest Arizona cotton acreage since 1921, according to the USDA. There are a lot of factors at play here. Water is just one of them. But Arizonans are using less of their scarce water growing cotton than they used to.