If you care about Colorado River Basin water, it behooves you to pay attention to the snowpack in California’s Sierra Nevada. It’s an entirely different watershed, but 2015 demonstrated how the interconnections in California’s plumbing have left the two inextricably linked.

The tl;dr version of two interrelated points below:

- California’s drought has put pressure on the Colorado River, as Southern California turns east for more water to make up for shortfalls from the north.

- Despite California’s problems, the overall Colorado River Basin is holding up – able in a subpar year on the Colorado to deliver the extra water to L.A. and San Diego while ending the year with total reservoir storage unchanged from last year at this time. The system is in a tenuous but encouraging balance.

California, the Colorado, and the West’s interlocking watersheds

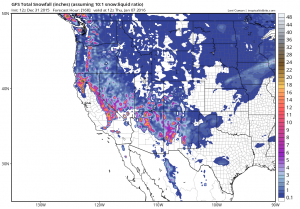

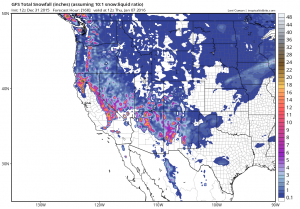

7 -day accumulated snow shows more help on the way for California’s watersheds. GFS model, courtesy Levi Cowan

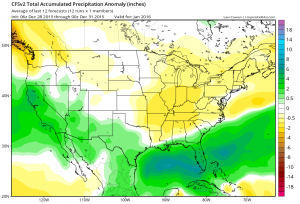

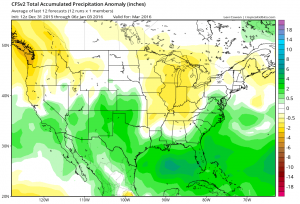

The good news in California is that, as of yesterday’s theatrical, made-for-media first measurements of the year, the Sierra snowpack is near normal for this time of year. That’s essentially twice as much snow as last year at this time. There’s lots of snow season left to push the numbers up or down, but for now it’s good news. And the current forecasts (see map to the right) call for more of the same.

Less theatrical is the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California’s low key success in running its Colorado River Aqueduct full bore this year, ferrying extra water from Lake Mead to coastal Southern California to make up for the shortfall in 2015 Sierra-fed water supplies. In particular, in addition to Met’s flexibility in water deals within California to move ag water to meet urban demand during the drought, there is 240,333 acre feet of water moving through the aqueduct that would not otherwise be there thanks to a historic 150kaf deal to send Las Vegas water Met’s way to help during the drought, plus another 90,333 acre feet in water that Met had banked in Lake Mead in previous years.

The result is that, at 1.178 million acre feet, Met’s take on the Colorado River this year is projected to be the largest since 2002 (source: USBR water accounting reports, 2015 year-end forecast updated today).

There are two ways of looking at this.

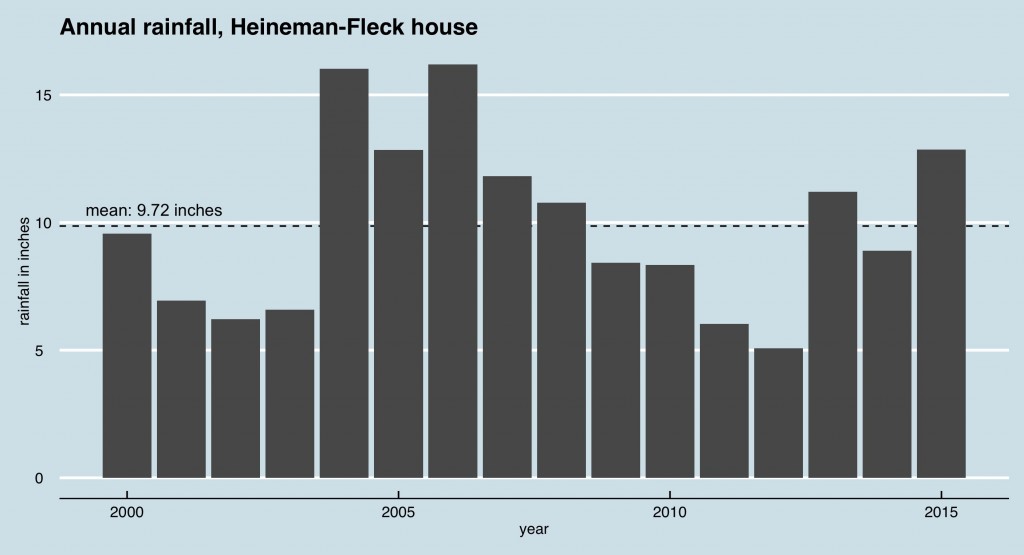

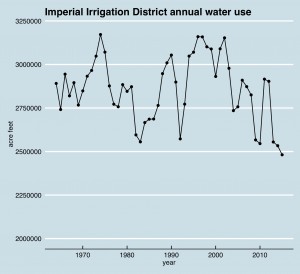

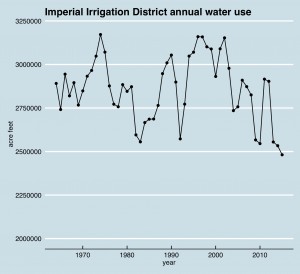

Water use by the Imperial Irrigation District. Data: USBR, graph by John Fleck

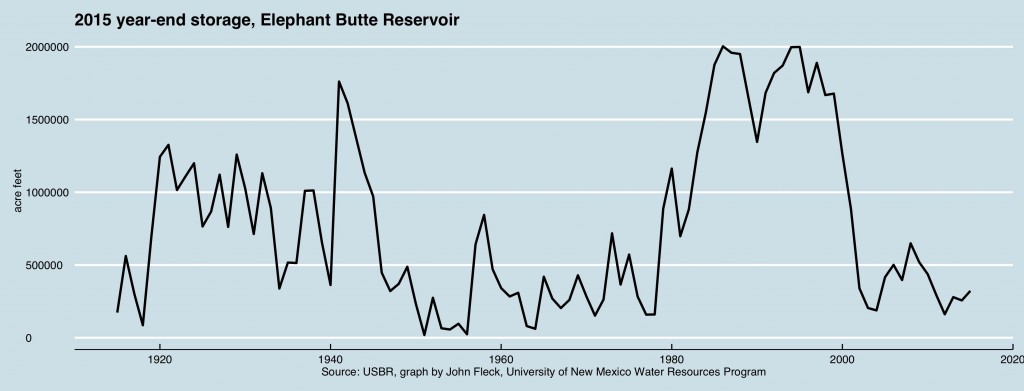

The foresight of Southern California’s water management community created diverse sources of supply that have allowed it to weather the unprecedented California drought. One purpose of big multi-year reservoirs is to store water in wet times so that it is available in dry times. Lake Mead has fulfilled that role, dramatically, during California’s current drought. That is a good thing. What good is a reservoir full of water if you can’t tap it when you’re faced with an event as extreme as California’s current drought?

California also has been building increasingly sophisticated water-sharing/transfer deals, including between the Imperial Irrigation District (where water use in 2015 was at record low levels) and metro water agencies.

But risk in California now poses risk in the rest of the Colorado River Basin, because of the interconnections we’ve built. My water supply here in Albuquerque, beyond the eastern boundary of the hydrologic Colorado River Basin, is now linked to snow that falls in California’s Sierra Nevada nearly 1,000 miles (600 1600 km) away.

Why 2015 nevertheless leaves me optimistic about about the Colorado

When I sat down this morning to look at 2015 Colorado River data with an eye toward a year end post, here is what struck me.

- The last water year was a bit below average (94 percent at Lake Powell).

- Current total system storage of 29.7 million acre feet is essentially exactly the same as last year at this time. (source)

So in a slightly sub-par year, and with California taking extra water in response to a historic drought, the Colorado River system remained, in 2015, roughly in balance. Absent California’s problems, net storage would have been up this year.

Importantly, with just 94 percent river flow, Lake Powell is up ~300,000 acre feet from a year ago, suggesting that Upper Colorado River Basin water users consumed less water than nature provided. Mead is down, Powell is up.

Of course, “absent California’s problems” invokes a useless hypothetical, because California did have problems. I could just as easily pose a hypothetical in the opposite direction: What if we hadn’t had that “miracle May” that bailed out an otherwise dismal year in the basin?