All the cool kids seem to be buying up real estate in the Palo Verde Irrigation District. First it was the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, which has upped its stake in the Colorado River farming valley to 22,000 acres. Now comes news that Almarai, a dairy company, bought 1,790 acres to grow food for its cows. I have no idea whether $18,000 an acre is a good price for California farmland with senior water rights. I do know that, based on the Law of the River, is there’s any water at all leaking through Hoover Dam, Palo Verde is among the first in line to get it, so Almarai’s lucky cows will be first in line to be fed while all those loser cows with junior water rights will be off to the hamburger grinder.

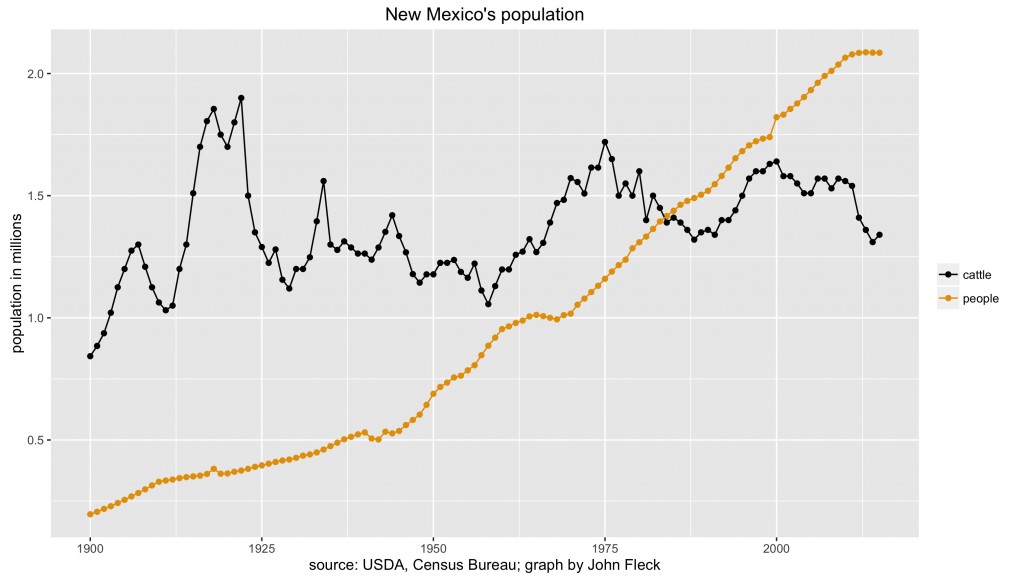

alfalfa exports

Palo Verde Irrigation District alfalfa, Blythe Calif., February 2015, photo copyright John Fleck

Almarai’s dairies are in Saudi Arabia, which does complicate the already complicated conversations we have about the use of Colorado River Basin water. Concerned about the overuse of water there, they are essentially buying virtual water here. How much? In 2014, consumptive water use in PVID average about 4 1/2 feet (4.5 af/acre), meaning this is the equivalent of ~8,000 acre feet of water, or about 1/10th of one percent of the U.S. water use on the Lower Colorado.

I don’t worry much about the export part. We use water to produce all sorts of things in our economy that we then export (computer chips in Chandler and Albuquerque, to pick the low-hanging fruit). We also import all sorts of “virtual water” from other countries in the form of food grown and products made there. It remains the case that the vast majority of the alfalfa grown in this country (97 percent by my calculation) is eaten by domestic critters, so it’s not like the export market, whether to China or Japan or Saudi Arabia, is a major driver at this point in the use of water on alfalfa fields in the United States.

the future of Palo Verde

The more interesting thing, it seems to me, is the future of farming in the Palo Verde Valley. As we head into a Water Knife future of armed helicopters defending the Law of the River, the attractiveness of Palo Verde land for its water rights is becoming an increasingly edgy topic for the community around Blythe, California. Met has tried to provide assurances that it plans to keep its PVID land in production, and I take the agency at its word. Clearly other folks were in line to try to buy the land when MWD swooped in and grabbed it. Those other buyers seem to have had other ideas, which apparently pointed toward shutting down farming and moving the water elsewhere. Nervous or not, Met seems preferable to the alternatives. To now have another couple of thousand acres bought up by Almarai, which seems to be committed to growing food on it rather than selling off the water seems to be to Blythe’s benefit.

But if I was in Blythe, I’d be nervous too.