A student in one of our University of New Mexico Water Resources Program classes asked last week what the magic trick was to finding water data. We’d asked the students to do some really challenging modeling of the flow of water through New Mexico’s Middle Rio Grande watersheds, and one of the biggest difficulties was finding usable data to plug into their models. My faculty colleague who’s helping teach the class (and who is one of the great data wizards of the Middle Rio Grande) didn’t have a good answer. Like all of us, he’s collected spreadsheets and bookmarks over the years that point in the right direction, but each question leads to a new data need. Water data is hard. Often it’s not collected at all, and when it is, it’s not standardized and connected up in ways that might make it accessible.

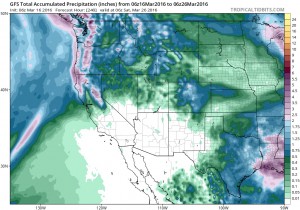

The result is that important policy questions – how might climate change impact agricultural acreage, or the need for groundwater pumping? what role might direct potable reuse of wastewater play? our students are smart, these are the kind of questions that interest them – are very hard to ask in any sort of a quantitative way.

My experience working with Western water data thus leaves me enormously sympathetic to the argument Charles Fishman made in yesterday’s New York Times about the need for better US water data:

Water may be the most important item in our lives, our economy and our landscape about which we know the least. We not only don’t tabulate our water use every hour or every day, we don’t do it every month, or even every year.

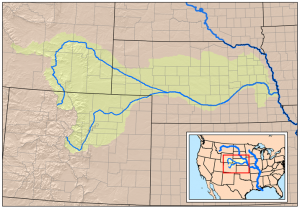

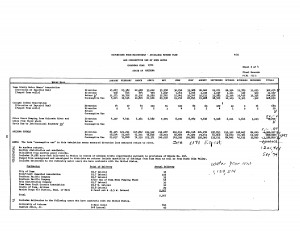

Water Data looks like this – USBR Lower Colorado Accounting, circa 1970

If you’re willing to put in the work, the problem can be tractable. On my hard drive is a precious collection of spreadsheets I collected over the last few years while working on my book – some provided by patient and helpful (and transparent! yay government sunshine!) water agency officials across the West, many built myself from old paper documents accumulated over the years. When a water district manager claims a reduction in summer irrigation, I now know where to go for the monthly totals through time to check it out. (Looking at you, Yuma County Water Users Association. And yes, the claim checked out.) But the current state of the data does not make this easy, and there are many, many geographies and categories of water use for which the data do not exist at all.

And even when the data does exist, it’s been collected in a particular way to meet a particular need, and comparisons across regions and water agencies trying to do the sort of apples-to-apples analysis that good regional<->national water policy requires is nigh impossible.

So yes, I’m in agreement with Charles – those of us trying to improve our nation’s water policies need better data to work with.

But I as I sit here in the midst of putting together a lecture for the students next week on the role of science in politics and policymaking, I am less clear than Charles about the direction the data<->policy arrows run.

Researching my book, I spent a lot of time trying to understand the places and the ways in which water governance has succeeded. My favorite example, which I spend a lot of time on in the book, is the West Basin regional aquifer in Southern California, south and west of downtown Los Angeles. (Here is the 628-page pdf of Elinor Ostrom’s PhD thesis on West Basin. Go ahead and read it, I’ll wait. It’s delightful.) There, the evolution of water governance and the provision of good water data went hand in hand. The evolving governance clarifies the need for data, and then better data feeds back into the evolution of better governance.

Simply collecting and providing good data runs the risk of what David Cash et al. call “the loading dock problem“, where science (in this case data) is collected by the sciencers and then handed to the policyers. This, they argue, is less useful than a two-way process in which those who would use the data help define the data that they need, and take ownership of and confidence in the results. What happened in West Basin very much involved the sort of “coproduction” of science Cash and colleagues describe.

Thus I am of a mixed mind about the usefulness of what Charles asks for:

Congress and President Obama should pass updated legislation creating inside the United States Geological Survey a vigorous water data agency with the explicit charge to gather and quickly release water data of every kind — what utilities provide, what fracking companies and strawberry growers use, what comes from rivers and reservoirs, the state of aquifers.

I fear that such a national effort, much as it might simplify my desire to have a better handle on the water consumed by the Colorado River Basin’s alfalfa farmers, is insufficient to spark the revolution Charles hopes for. So maybe call this “necessary but not sufficient”?