A flurry of public discussion over the last week about a possible water conservation deal on the Lower Colorado River illustrates the central dilemma in the river basin’s water use problems.

tl;dr This is a very important agreement. Modeling suggests that, if implemented, it could slow the steep decline in Lake Mead. The water conservation goals are achievable without crashing the West’s economy, but politics back home, in the individual states, remains the most important stumbling block.

The longer version:

The dilemma is this:

random picture of Hoover Dam and Lake Mead, meant to make it look really empty

At the scale of the basin as a whole (seven US states and two in Mexico), the river’s waters are overallocated. Members of the formal and informal governance network of water managers working at that scale all know that everyone needs to take less water.

The question of who takes how much less, and when, is a staggeringly difficult negotiation. But then – and this is the far harder part, the dilemma – the representatives of each state have to go back home and sell that deal to political constituencies who don’t work and think at the basin scale, people who are skeptical of any deal to give up water to which the feel they are entitled.

This is one of the central arguments in my upcoming book (preorder now if your opportunity cost of money is low and you’re willing to wait four months to actually read it) – the difference between basin-facing politics and the domestic-facing politics of water management back home. There is a great deal of evidence that across all water use classes and geographies, communities are capable of using less water without suffering significant harm. But folks don’t always realize this, and at the local level tend to cling to the security of their old paper Colorado River water allocations, even if there isn’t enough wet water to meet them all.

At the individual community level, this is rational. Voluntarily giving up water absent a broad water use reduction deal just means that other users will take more and the system can still crash. Collectively, if everyone acts on this local-level rationale, we’re screwed.

The Deal

As first reported by Tony Davis and then ably followed up by Ian James, Caitlin McGlade, and Henry Brean, The Deal calls for Arizona and Nevada to take larger reductions in their annual Colorado River allocation than are required under the current rules, and brings California into the allocation reduction scheme as well at some point in the future if the bigger Arizona and Nevada cuts aren’t enough to slow the decline in Lake Mead.

Water in the desert – the Colorado River’s Parker Strip

When I was finishing up the final draft of the book’s manuscript last December, the basic shape of the deal was emerging, looking a lot like what we see today. What wasn’t clear (and still isn’t) was whether it could be packaged in such a way that it could be sold to skeptical water users back home in the states. (As a newspaper reporter by training and inclination, this was a tricky problem. We’re used to having the next day’s paper to revise and extend our remarks as things change. How to write something in December, with this uncertainty hanging over the system, that will hold up next September? Buy my book! See how I did!)

It’s still not clear whether this deal can be sold back home, and there remain some subtle unresolved bits: “There are still significant issues that we need to keep working through. So we’re going to keep at it, and it may take several months. It may take another year,” California’s Tanya Trujillo told James.

Selling it in Arizona

It’s emerged into public view now because Arizona’s leadership decided it needs to get on with the task of lining up the political support it will need back home. As I’ve written elsewhere and as I argue in my book (On the shelves Sept. 1! Preorder now!), Arizona’s domestic water politics, especially its hostility toward California, is one of the biggest stumbling blocks to a deal.

Arizona has a long history of hating on California over water, but the biggest sting is the 1968 deal that allowed construction of the Central Arizona Project. The canal was necessary to get Arizona’s share of the river’s water to the people in the Phoenix-Tucson corridor who needed it, but it came with a price. To get federal legislation needed to build it, Arizona had to agree to junior priority, standing behind California in the water line should supplies run short. That means that in theory California could dig in its legal heels and force Arizona to take huge cuts without losing a drop. You can see that importance of that historic sting in Arizona Department of Water Resources chief Tom Buschatzke’s op-ed on The Deal. It is crucial for Buschatzke to convince Arizonans on this point:

California would take reductions as well, but not before the lake has fallen to still lower levels. Current law states that California does not take reductions in deliveries until the Central Arizona Project completely dries up. Equity and fairness demand a different outcome.

California’s water leaders have made clear, often in private and increasingly in public, that they realize that brinksmanship, clinging to their 1968 politically won senior priority even as supplies to Phoenix are cut to zero, defies a sense of rightness and equity about sharing the river’s water. This echoes a point Brad Udall made in a series of talks in the summer of 2013 that had a significant impact on my thinking. It always seemed clear to me that any deal would inevitably require California to take cuts too. California agreeing to this in a formal, legally enforceable way, would be a huge deal.

What does California get in return?

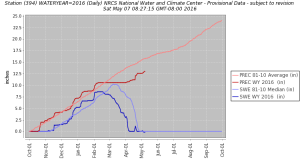

In terms of what is now publicly known about the deal, what California gets is an agreement by Arizona and Nevada to take deeper cuts, sooner, than the current Lake Mead operating rules allow. Modeling runs implementing the terms of the deal suggest that may be enough. Under a set of dry years they call the “stress test”, there’s a 50-50 chance that with the additional Arizona and Nevada cuts Lake Mead will never drop low enough to require California to take its first tier of cuts. But the model also shows a worst case (a one in ten chance) under the stress test that California might have to take cuts as soon as 2019. (The “stress test” models a set of dry years with flows 16 percent below the long term median of the system’s historic performance, to give a feel for operations under climate change/drought conditions).

I have a bunch more thoughts and questions (blogger’s prerogative, it’s the end of the semester and I’m focused right now on helping our UNM Water Resources Program students). I’m especially curious about the current state of domestic politics among California water agencies, and also some of the more arcane terms of the deal, like what’s up with Intentionally Created Surplus below 1,075 under the agreement?