We’ve had a healthy freakout over the last couple of weeks about the fact that Lake Mead, the nation’s largest and iconic water supply reservoir, is (again) at its lowest point in history (meaning the lowest since they built it in the 1930s). Brad Plumer has a good summary of what’s what. It’s an important symbolic milestone, suggesting that we’re heading into unsustainable water use territory by taking more water from the system each year than is returned by rain and snow upstream.

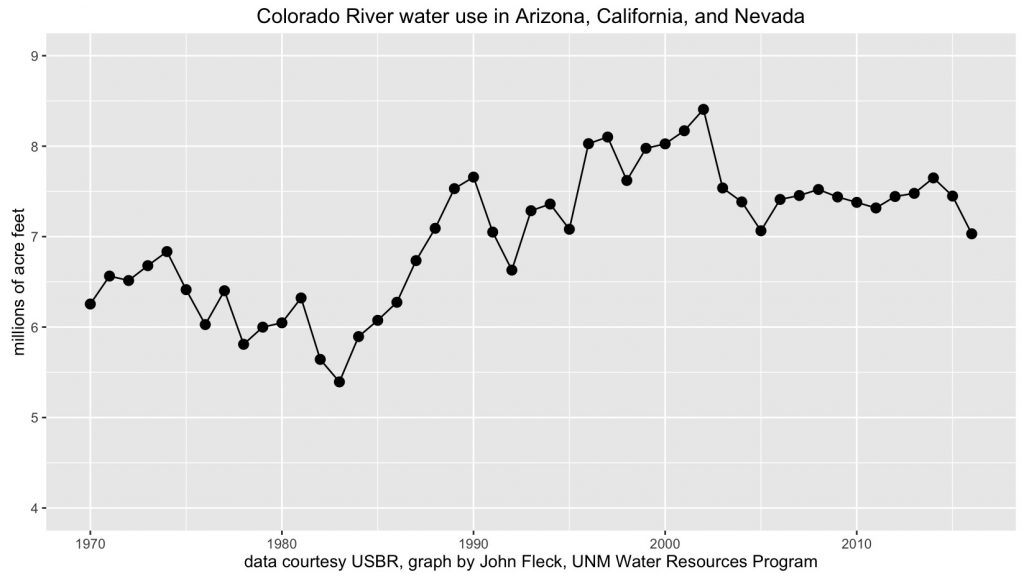

But in the midst of the freakout, there’s an important point that’s worth attention. The latest forecast for 2016 shows Colorado River water use in Nevada, Arizona, and California on track to be the lowest since the early 1990s. (I’ve plotted this back to 1970 because that’s a good starting point for the “modern era” of Colorado River water management.)

Colorado River water use

Under the current Law of the River framework, the three Lower Basin states are in theory entitled to 7.5 million acre feet of water. They’re only forecast to take 7.031 maf (data pdf here). What’s going on? A series of voluntary agreements aimed at slowing the decline of Lake Mead – an actual reckoning in on-the-ground water management of the reality that there is not enough water in the system for business as usual. Arizona, with the greatest risk because of its large take on the river and junior priority, is forecast to take 93 percent of its 2.8 maf allotment. California is taking 94 percent of its 4.4 maf allotment, and Nevada is forecast to take just 87 percent.

These cuts are not enough. Lake Mead is still forecast to drop another 2 feet in 2016. But the conservation measures being implemented in the Lower Basin states are unquestionably slowing Mead’s decline, demonstrating the institutional learning necessary for the Colorado River-dependent states to figure out how to survive on less water, and most importantly demonstrating that there can be a way to avoid the “tragedy of the commons” conflict path.