I was talking the other day about California’s struggle to solve its Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta problems with a friend who grows food with Colorado River water in California’s southeastern desert. The delta’s more than five hundred miles and three or four watersheds away as the crow flies from his farm. Why such a keen interest?

Courtesy California Department of Water Resources

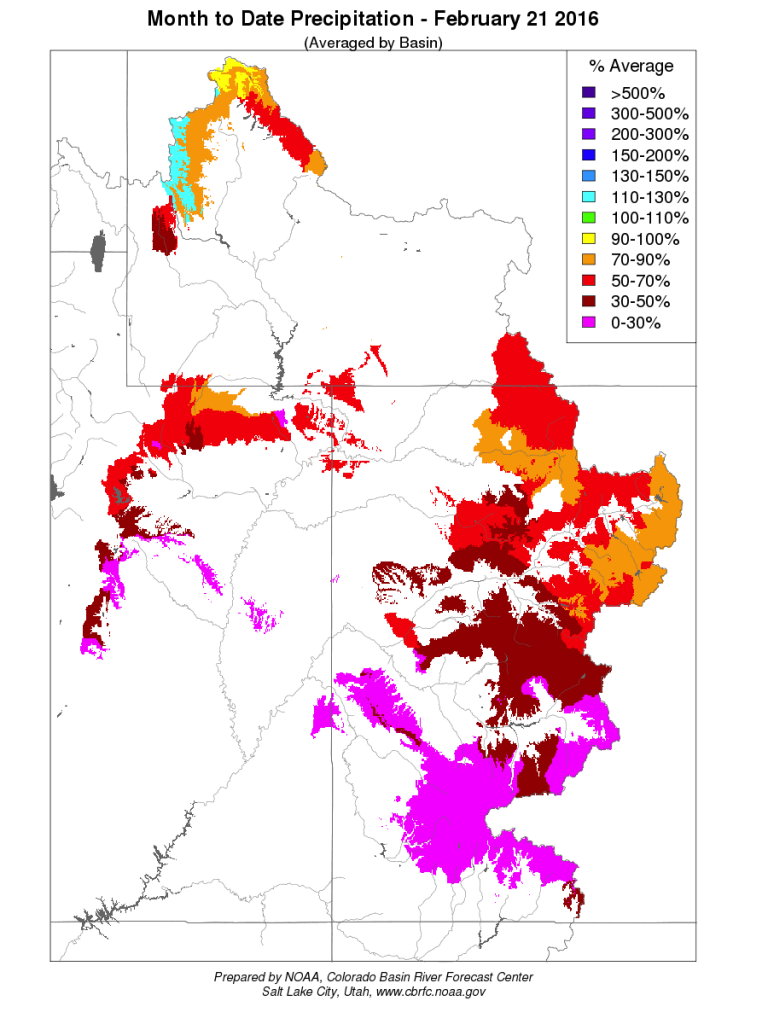

Here’s the map. My friend’s farm is near the Colorado River in the appropriately colored brown blob down in the bottom right corner. The Sacramento Delta is in the green bit in the center left, near the coast.

The problem lies in the political geography of California water. The Los Angeles-San Diego metro area (the lower green coastal blob on the map) gets large supplies of imported water from both places – the Sacramento Delta and the Colorado River. To the extent that supplies from one of those two places become smaller or less reliable, it places enormous pressure on Southern California to trade that problem off against increased supply and/or reliability from the other. (Both variables, supply size and reliability, are crucial.)

The Sacramento Delta is a mess, both in the plain English sense of the word (“a state of affairs that is confused or full of difficulties”) and in the more subtle framework of Berkeley policy scholar Emery Roe in which policy messes are things not to be cleaned up so much as managed. The Sacramento Delta mess involves a plumbing system that needs to pump vast quantities of water through an ad hoc network of old sloughs and channels ill-suited to the task, completely rejiggering the natural and human environment in a way that creates all sorts of reliability problems along conflicting dimensions – distant human water needs, local human water needs, environmental water needs, local and distant cultural values and needs. Building the big plumbing systems of the 20th century has created interconnections across social and governance boundaries that our 21st century institutions remain poorly equipped to handle.

AroundDeltaWaterGo

One proposed solution is to build ginormous tunnels beneath the damn thing, bypassing the water. California keeps changing the name of this project – it was once a Peripheral Canal rather than a tunnel system, it was the Bay-Delta Conservation Plan, I tried to name it Peripheral Thingie but failed, it’s now California WaterFix, my favorite new name is OtPR’s AroundDeltaWaterGo. More importantly, California keeps not quite deciding to build it, but also not deciding to not build it.

Water behind Imperial Dam is currently headed for desert farms. But will L.A. need it? photo by John Fleck

I am agnostic about whether AroundDeltaWaterGo is a good idea or not. I haven’t spent the time to form an informed opinion (do jump into the comments and explain what an idiot I am for not seeing the obvious merits of your argument for/against). But sitting out here in the Colorado River Basin I am acutely aware of the regional implications of how California handles this mess.

Jeff Kightlinger, head of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, has been on a public tear lately arguing the merits of the tunnel scheme:

California WaterFix proposes to build three new intakes in the northern Delta that are outside of the typical migrating range of adult delta smelt. The intakes since January could have been capturing as much as 9,000 cubic feet per second of supplies in addition to what we have been diverting from the existing south Delta facilities.

How much water are we talking about? Every day we cannot capture 9,000 cfs in supplies because we don’t have California WaterFix on line, the lost supply is roughly six times the daily demands of the cities of Los Angeles, San Diego and San Francisco combined.

To the extent that Met can’t grab that water from Northern California, it increases the pressure to look elsewhere. And my farmer friend and his neighbors in the agricultural communities of the deserts of southeastern California – the Imperial Irrigation District, Bard, the Palo Verde Irrigation District – are that “elsewhere”. The ag districts have Colorado River water rights, and Met has an aqueduct that could bring some of that water to the vast metro areas of the coast.

Met right now looks like it has to play a zero sum game. I can see why a farmer in California’s eastern deserts might have some enthusiasm for construction of giant tunnels 500 miles away that will bring him zero water.