The Griegos Lateral, a Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District irrigation canal in Albuquerque’s North Valley. Also a lovely bike route!

I left for my Sunday morning bike ride today as early as an alarm, coffee, and breakfast would allow – to beat the heat.

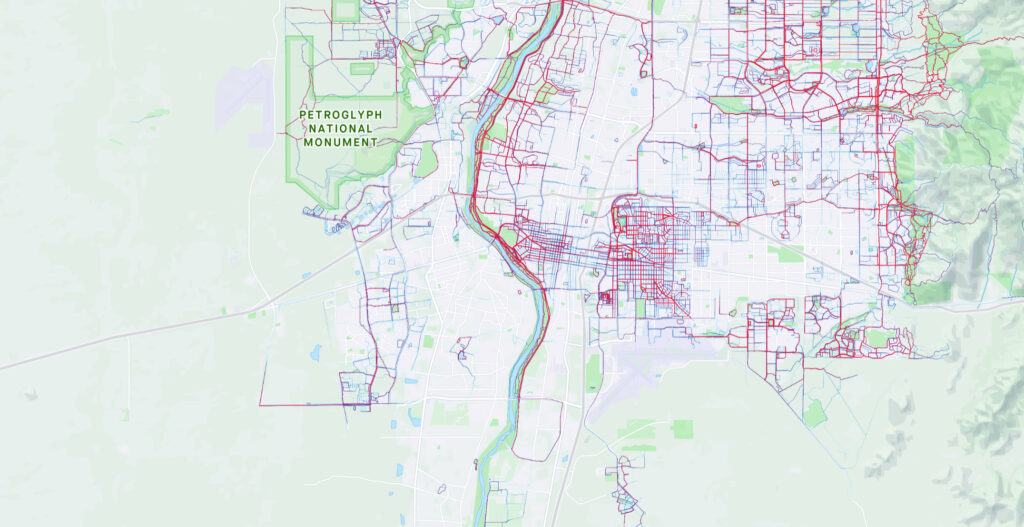

To structure the route, I set myself a puzzle: to ride from Albuquerque’s Old Town, paralleling the Rio Grande to the north, all the way up the valley to the north with a minimum – ideally zero – time spent on busy streets. There’s no way to avoid crossing busy streets, which are like alligator-filled moats. And there are a couple of quite safe routes on small main roads with good bike lanes. But – my puzzle, my rules – those were off limits.

This of course would be trivial on the riverside bike trail, but, to paraphrase Yogi Berra, nobody rides that trail any more on the weekends – it’s too crowded.

I’ve ridden the north valley many dozens of times, and had a rough idea in my mind of the puzzles pieces I needed to assemble – a handful of twisty old country lanes, interconnecting ditchbanks, crucial alligator moat crossings, the critical breakfast burrito stop. But part of the fun was assembling the pieces on the fly, so I didn’t want to over plan.

A friend and I have done this on the west side of the river – we dubbed it the “Northwest Passage.” But we’ve strangely never done it on the river’s east side. So “Northeast Passage” was the goal as I set out before sunup this morning.

This is really about the book

This is, of course, a misdirection.

We got the latest round of editorial feedback last week for Ribbons of Green, the book Bob Berrens and I are writing. The feedback was useful, in particular in showing areas where the points we are trying to make did not come through with sufficient clarity.

I’m excited to dive back in, but there is this personal temporal challenge in writing a book. You spend a bunch of time writing, fully immersed, you hand it off into an editorial process, and then you go on to thinking about other things. And then the manuscript returns, months later, in need of love and attention.

Much of what I’m thinking about overlaps with the issues in the book, but writing a book, and now revising it, are full brain activities. I need to yank my brain back into Ribbons of Green.

So I spent six hours this morning riding my bike, slow AF, through our book’s landscape.

The Old High Ground

Sunup in Old Town

I hit Old Town, the plaza where one of greater Albuquerque’s villages was founded in 1706, around sunup. Like all the key human landmarks of the old landscape, it was built on slightly higher ground, a pattern that left traces that define the modern landscape in ways that show up, again and again, in the book.

The ditches and old twisty roads follow that slightly higher ground – that feature of the landscape was central to the bike riding puzzle.

Modern Albuquerque Old Town is a wonderful combination of cheesy tourist fluff and community center. The San Felipe de Neri Catholic Church was built on its current site on the plaza’s north side in 1793, but the parish dates to the village’s founding in 1706. As I rode through the center of the plaza, people were converging for early mass. It’s still a working church.

A couple of alleys to the west led me to Gabaldon Road, which turns north at what was once the edge of the river’s flood plain. The Rio Grande’s main channel, pinned between levees, is now nearly half a mile to the west, and this part of former flood plain is filled with houses. The road passes what was once Palmer’s Slough, where city kids in the early 20th century would go swimmin’, and sometimes drownin’, until they filled it in because of pestilence and whatnot and built houses on top of it.

Gabaldon met my “country lane” puzzle rule, but the Duranes ditch, which for over 300 years has been spreading water across the flood plain for human use, was even better. It jogs north through a modern subdivision called Thomas Village, built on an old swamp. Modern subdivisions are often built atop old swamps, land that was available as the swamps were drained.

The Duranes does significant work in our narrative – a centuries-old irrigation ditch that serves as a modern urban amenity, irrigating a bit, and shading the ditch walkers. And bicyclists!

Guadalupe Trail

After a couple of ditchbank miles to the heading of the Duranes, I switched over to the Griegos Lateral (“before 1800” in my 19th century guide to the ditches of Albuquerque) until I hit one of the modern drains. “Modern” is a relative term here. In a landscape threaded with ditches dating to the 1700s, the Griegos Drain is a youngster at 90-plus years old. The drains were crucial to the making of modern Albuquerque, lowering the water table and allowing a city to emerge from the swamps.

The drains are also crucial to low-stress cycling, with big wide service roads. They’re not always rideable – they can get sandy, and drainside riding can lead to a good deal of walk-a-bike through the sandiest bits. And they’re mostly not nearly as shady as the irrigation ditches. But the Griegos Drain is special to Bob and I, because it’s where we first dug down into the old maps in detail to understand the relationship between the old swamps and the modern city. Crossing the alligator moat at Montaño Boulevard, I followed the ditchbank past what was labeled a “lake” in the 1920s map, a swampy piece of land owned by Melquiades Montaño now home to a city-owned expanse of farmland.

With the water table lowered by more than a half century of urban groundwater pumping, the drain doesn’t have a lot to do these days, and its northern reaches have been abandoned, so I jogged east to a lovely street called Guadalupe Trail. It’s one of the old ones, twisting and starting and stopping, pavement laid down on an old wagon route through the North Valley. When I first started riding in Albuquerque a quarter century ago, a friend gifted me Guadalupe Trail, and I’ve always treasured it.

Water in the desert.

Guadalupe Trail is home to some of Albuquerque’s most ostentatious, well-irrigated wealth. This raises questions about equity in the allocation of water under conditions of scarcity, which are a big part of what I’m thinking about lately, but which are largely beyond the scope of the book. But it’s hard to look away when you’re rolling slowly by on a bike and see the sprinklers. This sort of thing is why I assigned myself the bike ride puzzle.

Lately I’ve been taking my morning rides through some of Albuquerque’s poorest neighborhoods. They are noticeably less green, both to a dude wandering around on a bike and also to a dude who spends an inordinate amount of time poking at the satellite data to try to better understand, quantitatively, where Albuquerque’s water conservation success is most noticeable. A subject for another bike ride essay on another day. As I said, beyond the scope of the book. Pay attention to the book, John!

Brunch

The closest thing to a busy street came at the upper end of this section, where I diverted into the urban busy-car landscape for a breakfast burrito. It was still early, but breakfast burritos are key for umpty-hour bike rides. Properly packaged, they fit in a cycling jersey back pocket. Or today I was riding with a pannier. Five or so bites every few miles, and I can ride for hours.

The Albuquerque Main

I refilled the water bottles, and turned back to the Chamisal Lateral, another of the old twisty ditches that follows the high ground the rest of the way north, all the way to the Sandia Pueblo, the indigenous community on Albuquerque’s northern border. Looking back at my old bike ride GPS traces, I see a few rides on bits of the Chamisal, but I’d never ridden the whole thing, which is a shame. Now I know.

At its northern end, the Chamisal’s heading draws from the Albuquerque Main Canal, a larger canal that is mostly big and straight, built in the 1930s as the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District’s early works were consolidating irrigation in the valley, in pursuit of the development of commercial agriculture here.

It’s the “straight” part that’s the clue to the socio-hydrologic history. The old ditches are twisty. The modern ones are straight. The old roads are twisty. The modern ones are straight. Or when they curve, it’s a planned, drafting-tool curve, not the wander of a foot path turned into a horse path turned into a wagon path turned into a street.

This is why I ride.

“Now I can ride all day!”