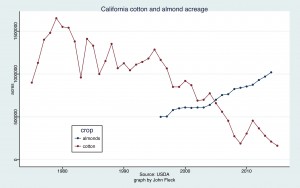

In his keynote at last week’s Law of the Colorado River conference in Las Vegas, Metropolitan Water District General Manager Jeff Kightlinger pointed out something that’s not gotten a lot of attention in discussions of California’s drought – the extraordinary decline in that state’s acreage of cotton. Cotton’s gotten a bad rap in irrigation circles, because it’s subsidized and thirsty. Despite those subsidies, as I’ve written, cotton acreage in Arizona has plummeted, which is why I don’t see the cotton subsidy as a big piece of the western water problem. But I didn’t realize the size the decline of California’s cotton industry.

Source: USDA

Last year there were 164,000 acres of cotton grown in California, just a tenth of the 1979 peak of 1.65 million acres. Given cotton’s thirstiness, that drop would seem like a good thing in water management terms. But Kightlinger pointed out that a big part of what we’ve seen is a shift away from a temporary field crop like cotton, which can be fallowed in a dry year, to permanent almonds. In the old days, when Met wanted to go out on the market and buy ag water during a dry year, farmers could fallow a field crop like cotton and take the money. But last year, Kightlinger explained, Met ended up having to bid against almond farmers with a lot of investment riding on keeping their orchards alive. As a result, there wasn’t a lot of ag water to be had in Met’s price range, and the agency ended up shifting the money to a turf grass buy-back program in Southern California – fallowing lawns, if you will.

It’s not been a one-for-one acreage switch. Since 1996 (that’s as far back as I could find the almond acreage to do the comparison), cotton acreage has dropped by nearly 900,000 acres, almost all of that in the San Joaquin Valley. (California alfalfa, the other high water, low value irrigated crop is down ~150,000 acres statewide during that period.) Almond acreage during that time is up about 500,000 acres. So the net in acreage of those big three irrigated crops is down a lot, with the almond increase more than offset by the cotton and alfalfa decrease. But while that means less total water use, Kightlinger’s argument points out the loss of flexibility in the shift to crops that you can’t fallow when the water runs short.