On my way home from Boulder Saturday, I diverted off the interstate and up over a low pass into the San Luis Valley of southern Colorado, where the Rio Grande (or its Mexican name, the Río Bravo) starts its long, frequently interrupted journey to the sea.

It’s a broad, flat, high desert valley, 7,500 feet (2,300 meters) in elevation, less than 10 inches of precipitation a year on the valley floor. But between groundwater and the river, it’s become a robust agricultural region. According to the new basin plan (pdf, a part of Colorado’s water planning effort), farmers in the valley have 523,000* acres under irrigation, which is comparable to the vast acreage of the Imperial Valley in southern California. But it’s a different kind of farming. With a shorter growing season, San Luis Valley alfalfa growers, for example, get a yield of 3.15 to 4.5 tons per acre. In desert climates of the lower Colorado River, where there is nothing one might call “winter” to get in the way of crop production, you can get something close to twice as much alfalfa per acre. But there’s a relationship between the consumptive use of water and the amount of crop grown. To first order the farmers in San Luis both use less water per acre and make less money per acre than the farmers in Imperial. (I don’t know of any dollars/crop per unit of water comparisons – that would be interesting.)

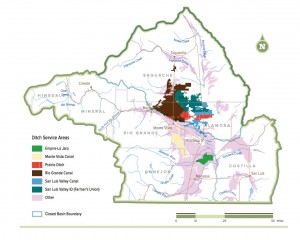

The governance structures also are different. In headwaters regions, you have many diversions from the many tributaries that gather the water. You have many governance structures to match that. So in the San Luis Valley, you have six major ditches, each with its own governance structure, and many more small ones. In the lower reaches all the waters have collected into a single river and you have more centralized diversions, and more centralized governance structures to match – in Imperial, for example, the Imperial Irrigation District. The Rio Grande is a lot like the Colorado in this regard.

The other thing about the San Luis Valley that’s different from Imperial is that the high mountain valley, as you can see from the picture, is gorgeous. It’s been wet this spring, and the Rio Grande was big when I crossed it at Alamoso, but the gauges suggest it was a lot bigger upstream, before the farm ditches snagged their share. I’ve a fondness for the low desert farm valleys like Yuma and Imperial, but I realize that is not universally shared. It’s an acquired taste.

* The Census of Agriculture puts the acreage at 387,000 acres (pdf), illustrating the maddening difficulty of figuring out how much land is under irrigation in the West. In putting together this post I reread the methodological bits in Mike Cohen’s invaluable Pacific Institute report on Colorado Basin ag, which would be hilarious if the process he describes were not so painful.

** Thanks to Matt Hildner who covers the San Luis Valley for the Pueblo Chieftain for helping me understand a bit about how valley plumbing works.

Nice chatting this morning. Think the census figure of 300,000 acres is the outlier. 523,000 acres is closer to all the ones I’ve seen, although irrigated acreage is likely to shrink in the next 5 to 10 years as state groundwater rules and voluntary pay to pump schemes come into play.

Generally when I travel through the San Luis Valley (US285 is a beautiful drive to metro Denver) there is visible surface water. I’m told that the water table is very high in the area.

Some years ago there was a plan by out-of-state corporate entities to buy up water rights and pipe it west. Valley residents sounded an alarm, and that plan never was developed.