I took a break today from the excitement of following a newly rejuvenated Colorado River south, across the border into Mexico, where it rarely flows, and followed “the river” west instead.

Forty-nine river miles upstream from the “Southern International Boundary” – essentially the bridge at San Luis Rio Colorado – a structure known as Imperial Dam diverts the majority of what is left in the Colorado River into the All-American Canal. The canal, which carries about 3 million acre feet of water per year to the farms of the Imperial and Coachella valleys, is far larger than the river that remains. The people standing at its edge in the picture above give a sense of the scale of this thing. It’s huge. Lined for part of its length with concrete, it’s obviously not a “river”, but it’s something like one.

Following it west, the All-American Canal splits into four giant mains that distribute water across what was once the dry desert of the Salton Sink – three canals to the Imperial Irrigation District and a fourth to the north, to the Coachella Valley. There, you can see the tradeoff we’ve made – dewatering a river in service of agricultural magic, the basic human goal of growing food. This is a geography profoundly altered by the irrigation revolution of the twentieth century. For a water nerd, it’s endlessly fascinating – a complex distribution network for the river water and an equally complex network of drains that carry waste water away from the fields and into the Salton Sea. For a water politics and policy nerd, it’s a central part of the story.

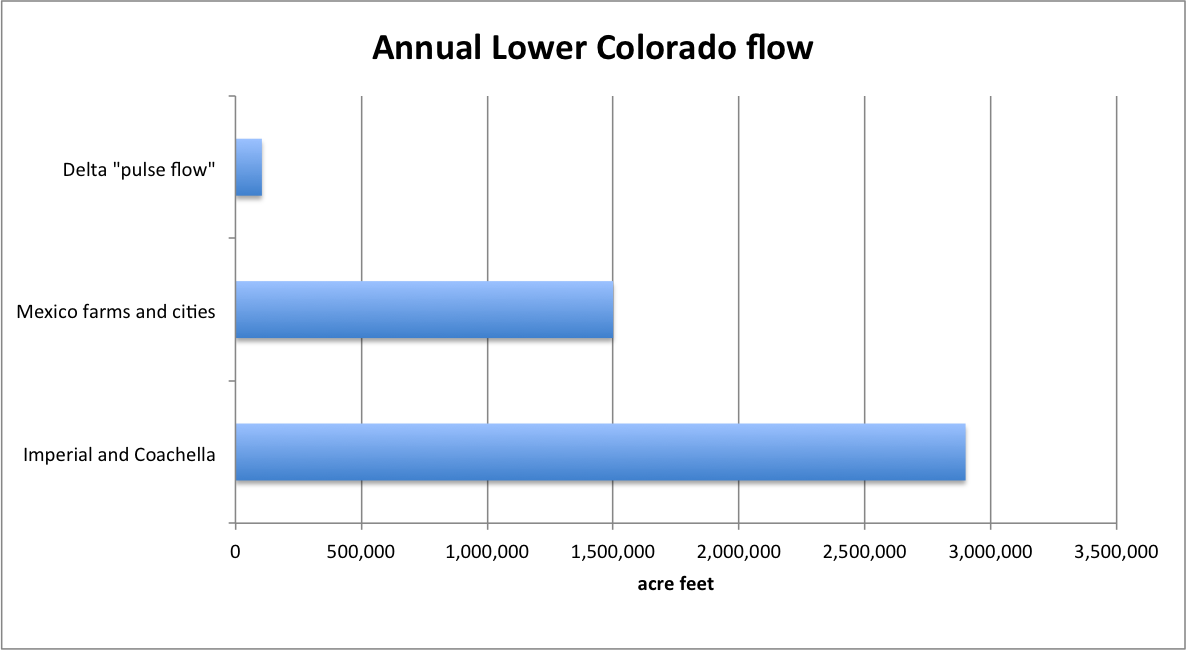

Here’s why. For all the fuss and excitement about the “pulse flow” to the delta (a fuss I think is warranted and an excitement I share), the amount of water turned to human use in this part of the river dwarfs the water we’re sending down from Morelos Dam and past San Luis:

Water is no one thing. Different groups of people value it and draw meaning from it in different ways. Farmers value it to grow food. Community members value a living river flowing through their midst. No one’s “right” here. The trick is negotiating the terrain of competing values. The size of those bars suggests the outcome of that negotiation over the 20th century. We mostly valued water for farms and cities. That’s not going to change. But if the modest flows involved in the current experiment have the desired effect, we can almost certainly find the slack in the system to meet both sets of values here. That’s what is really hopeful in all of this.

Pingback: AMACRQ: Colorado River Use Bar Graph | jfleck at inkstain