The JAWRA blog had a post Friday on something that I’ve found maddeningly difficult to explain to newspaper readers: the cases where water conservation efforts don’t really save the water one intuitively thinks they do:

Lining a canal, for example, may seem like “saving” water, but not if the leakage is replenishing a stressed aquifer.

For example, low-flow toilets in a place like Albuquerque, where return flows from the sewage treatment plant re-enter New Mexico’s water inventory via the Rio Grande, don’t generate the savings one might assume. To be clear, they’re probably a good idea for a variety of reasons, but a gallon saved at the toilet tank does not translate to a full gallon saved for the overall New Mexico water system.

At a water conference I attended several years ago, water historian, lawyer and judge Gregory Hobbs of Colorado explained how difficult a point this has been to get across in his state. Irrigators want to line canals to “save” water, but Colorado’s water law recognizes that the seepage replenishing groundwater is really water benefiting other water system users.

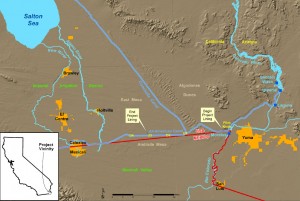

The most intriguing example of this right now here in the western United States is the lining of the All-American Canal, which diverts Colorado River water at Imperial Dam to provide irrigation and municipal water for the Imperial Valley. California water managers, desperate to squeeze every last drop from their Colorado River allotment, have turned to a concrete lining on 23 miles of the historic canal, which was built as a simple dirt channel. (OK, not so “simple”, it’s huge, one of the largest structures for moving water ever built, but you get the idea.)

The move will save an estimated 67,700 acre feet (84.5 million cubic meters) of water each year. But “save” here is a relative term. That water is soaking into the ground, where it replenishes an aquifer used by residents of the Mexicali Valley, across the U.S.-Mexico border. The attitude of U.S. officials toward the Mexicans’ loss is that it is not the United States water users’ problem. From a 2005 letter from U.S. Interior Secretary Gale A. Norton to Secretary Jose Luis Luege Tamargo, Secretary of Environment and Natural Resources of Mexico:

This important project was authorized by Congress in order to conserve Colorado River water reserved to the United States under the 1944 Treaty between our nations regarding, among other provisions, the allotment of the waters of the Colorado River for any and all sources. . . . As these ongoing discussions between our nations are coordinated through the State Department and [the International Boundary and Water Commission], our efforts will continue to reflect our view that the United States does not have an obligation to mitigate for any potential effects in Mexico of lining the All American Canal and that each nation must continue to explore and develop mechanisms to improve the efficient use of the limited water supplies of the Colorado River.

The U.S. government also concluded that our nation’s environmental laws, including the Endangered Species Act, do not apply to effects caused by the project in Mexico.

More reading:

I couldn’t agree more. “Save” is a relative term I spend much of my time balancing irrigation supply with growing urban and environmental water demand. Nevertheless, flood irrigation has long been touted as an inefficient means of water use. Although, this tends to be a double edged sword:

Edge 1. Flood irrigation dries streams and diverts much more water than is consumptively used by the crop.

Edge 2. Flood irrigation recharges aquifers, increases return flows, and supplies less consumptive use than sprinkler irrigation.

Here is the link for a brochure we wrote that that gets right to the root of this issue, written specific for Colorado but useful for understanding the matter elsewhere too. http://www.cwi.colostate.edu/other_files/Colorado_Ag_Water_Conservation_Brochure.pdf

MaryLou Smith

Colorado Water Institute