Crews monitoring New Mexico’s Middle Rio Grande reported yesterday (April 14, 2025) that the river’s still flowing past the San Marcial railroad bridge. Just downstream of the bridge, the USGS gage dropped to zero flow yesterday morning. We’re at the pivotal moment when the fact that you have to go out and look, and finding a ribbon of continuous water, however hard to measure with a gage – the river is still flowing – counts as news.

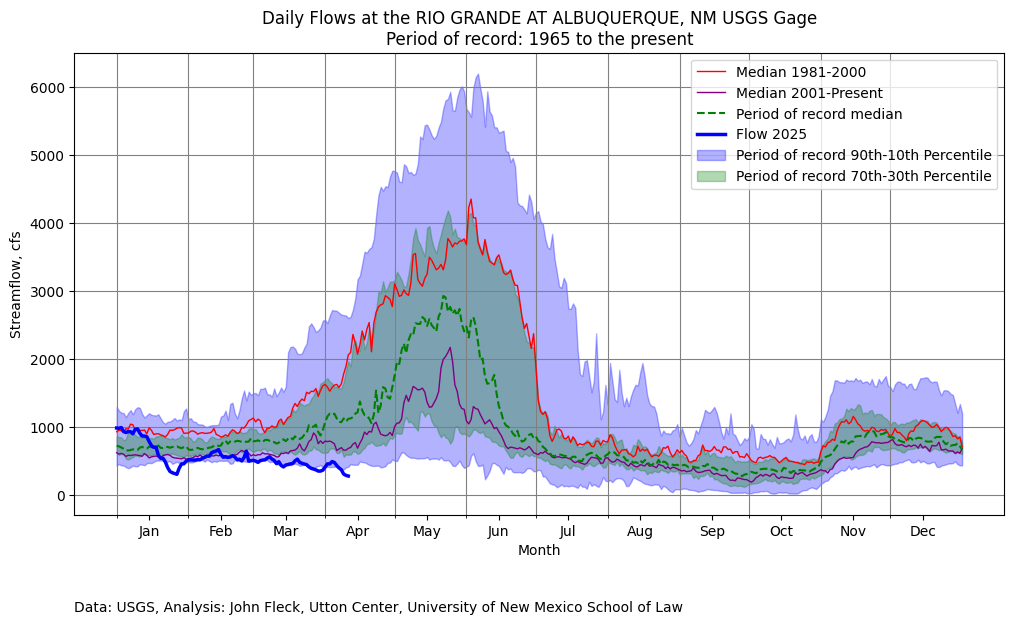

The Rio Grande through central New Mexico will begin drying soon from the bottom up, as the meager flows coming in from upstream disappear:

The Rio Grande through central New Mexico will begin drying soon from the bottom up, as the meager flows coming in from upstream disappear:

- into a web of canals that distribute the water across its former flood plain

- into the ground to fill the space left behind by groundwater pumping by cities and domestic well users

- into the air as the trees along its length suck up its moisture

- and then into the desert sands around San Marcial.

River drying in May is rare and bad. The fact that the river’s on the brink of beginning to dry in mid-April is worse.

Water for irrigators

Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District water operations manager Anne Marken reported at yesterday’s board meeting on the crazy institutional hydrograph we’re now seeing. Flows are up for now on the Rio Chama, but that extra water won’t be making its way down to the Middle Valley right away. Instead, it’s being stored for use later in the year by the Middle Rio Grande Pueblos, which have senior rights under the 1928 legislation that provided federal funding to create the District works. There’s continuing tension over this, because storing more water to meet legal obligations to the Pueblos (which have senior water rights) means less water for non-Indian irrigators. Lots of cryptic signalling about this debate at yesterday’s MRGCD meeting, but little explicit discussion of the hydrologic, economic, social and cultural tradeoffs involved. This is the kind of tough stuff that has to be dealt with in coping with dry years.

Storage in Abiquiu is going up, and the Bureau of Reclamation is adding a little bit of water to El Vado, the busted dam on the Rio Chama that can hold a little bit of water despite its shortcomings. I’m not privy to the internal accounting, but this appears to be Pueblo “prior and paramount” water.

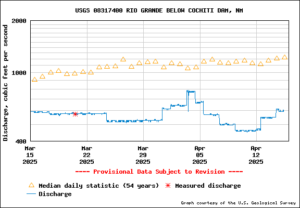

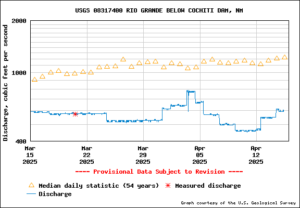

Cochiti releases

Also at yesterday’s meeting, MRGCD leadership was unusually vocal about frustration with the way the Corps of Engineers has been managing Cochiti Dam releases – lots of ups and downs that have made it hard to manage diversions for irrigators, as district chief Jason Casuga explained in unusually blunt terms.

As I said, this is the kind of tough stuff that has to be dealt with in coping with dry years.

The Bureau of Reclamation has money for some supplemental environmental flow water water this year, imported San Juan-Chama Project water. But there’s very little of that. (The e-flow water helps the irrigators – the fish don’t consume it!)

With no water in storage from previous years, Middle Valley irrigators, as we’ve said before, will have a very water-short year this year. What we’re seeing right now may be the most we see this year.

Marken:

So I wish I had better news, but I I think this could be one of the most challenging irrigation seasons the Middle Valley has experienced in recent history. And you know, as always, I encourage everyone to pray for rain.