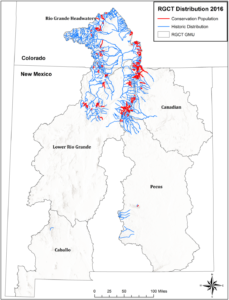

Courtesy New Mexico Department of Game and Fish

The US Fish and Wildlife Service earlier this month (December 2024) once again declined to list the Rio Grande cutthroat trout as “endangered.”

It’s a native species endangered (in the colloquial sense, not the legal sense) by both anthropogenic habitat changes (warm temperatures, less water, dams and stuff) and non-native immigrant species.

USFWS identified non-native hybridization and competition as the most significant threat, and concluded that collective action by a collaborative effort including federal, state, and tribal governments, along with NGOs, has successfully stabilized the fish’s population since discussion about possible listing first began a quarter century ago.

The 119 populations are distributed across a wide geographic area, providing sufficient redundancy to reduce the likelihood of large-scale extirpation due to a single catastrophic event. Furthermore, the Rio Grande cutthroat trout Conservation Team has a demonstrated track record of responding to negative events to protect and even expand populations in the aftermath of large-scale changes to streams. Populations cover the breadth of the historical range, ensuring retention of adaptive capacity (i.e., representation) to promote short-term adaption to environmental change. The SSA report describes the uncertainties associated with potential threats and the subspecies’ response to these potential threats, but the best available information indicates the risk of extinction is low. Therefore, we conclude that the Rio Grande cutthroat trout is not in danger of extinction throughout all of its range and does not meet the definition of an endangered species.

ESA questions

I’ve not followed the Rio Grande cutthroat trout saga closely. My primary interest is in its value in highlighting broader issues around the ESA that my Utton Center colleagues and I have been discussing of late.

Collective action

Collective action by a broad coalition of stakeholders before ESA listing seems to have been key in protecting what’s left of the species and avoiding listing.

Question: Is this driven by a societal environmental value (We love this fish and the ecosystems on which it depends, and want to protect them!) or a desire to avoid the messiness of ESA listing and the resulting land and water management craziness that would result therefrom?

In the new book, we note a clear distinction between these two types of cases in the history of Albuquerque’s relationship with the Rio Grande: environmental actions growing out of collective community values, and environmental actions driven by statutory (in this case ESA) mandates.

Charisma

Charismatic?

We know that charismatic species get more societal love. (Woe is our diminutive Rio Grande silvery minnow.) The Rio Grande cutthroat trout is charismatically beloved. Does this help explain the energetic collective action we’ve seen?

Loper Bright for the “foreseeable future”

Reading the USFW federal register notice in light of the Supreme Court’s Loper Bright decision, is interesting. IANAL, but my shorthand for the decision is that the courts no longer must defer to an implementing agency’s interpretation of ambiguous statutory provisions. Here’s USFWS in the cutthroat trout decision:

The Act does not define the term “foreseeable future,” which appears in the statutory definition of “threatened species.” Our implementing regulations … set forth a framework for evaluating the foreseeable future on a case-by-case basis…. The foreseeable future extends as far into the future as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service (hereafter, the Services) can make reasonably reliable predictions about the threats to the species and the species’ responses to those threats. We need not identify the foreseeable future in terms of a specific period of time. We will describe the foreseeable future on a case-by-case basis, using the best available data and taking into account considerations such as the species’ life-history characteristics, threat projection timeframes, and environmental variability. In other words, the foreseeable future is the period of time over which we can make reasonably reliable predictions. “Reliable” does not mean “certain”; it means sufficient to provide a reasonable degree of confidence in the prediction, in light of the conservation purposes of the Act.

Maybe language like that was always included in USFW Federal register notices? I expect a lot more post-Loper Bright debates about what Congress intended.

In October 2023 I was a part of a Sierra Club service team doing a fish survey with the Park Service biologists in the Valles Caldera above Jemez. It was a wonderful experience that I would recommend to anyone who’s not afraid of hard work. We sure pulled a lot of trout out of those streams but mostly Browns and Rainbows that are strictly speaking invasive. I recall a few Cutthroats but not many. Where I’m originally from in Wisconsin any day you catch a trout is a good day whether it’s invasive or not 🙂

Thanks for this, John. Interesting, but not surprising that USFWS doesn’t consider climate change and wildfire as principle threats. Hybridization threats have been significantly reduced by agency efforts. The Rio Grande cutthroat trout is a sport fish with considerable backing from the diverse crowd of supporters, and NMDGF. This decision is likely for USFWS to acquiesce to NMDGF and has little to do with species conservation. For the native Gila trout in SW NM, wildfire threats to isolated populations is paramount and it’s still listed. Under the ESA. Rio Grande cutthroat trout should receive the same consideration.