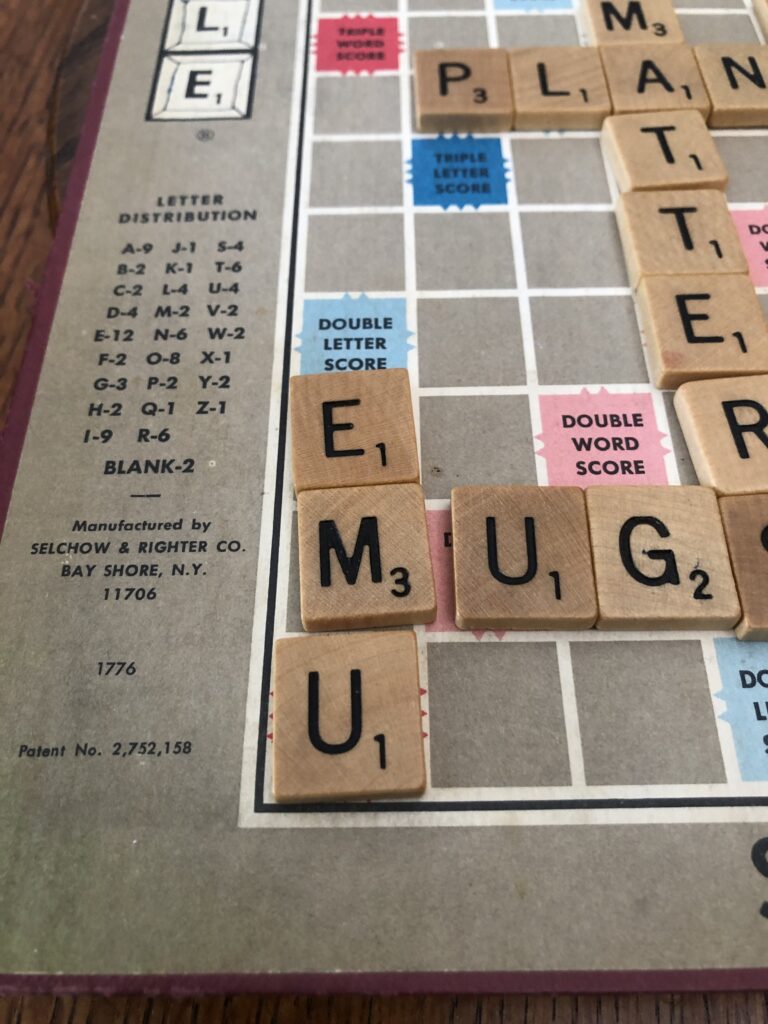

A fine word.

We had a round of holiday Scrabble this afternoon after first feast. I got “emu,” which is a fine word.

I never really got Ludwig Wittgenstein when I was studying philosophy in college. A lost opportunity. I’ve always been interested in words as objects, since I was a kid scribbling in notebooks, before my first typewriter.

Magical – written words on a page, objects, little vessels of meaning.

Ed Ruscha

It might have been the Spam.

In 2003, the Gagosian Gallery in Los Angeles showed a group of photographs taken in 1961 by the artist Ed Ruscha. Among them was a photograph of a can of Spam. Here is the Ruscha scholar Lisa Turvey:

Each Product Still Life features a single consumer item-Oxydol bleach, Sherwin-Williams turpentine, Wax Seal car polish-on what appears to be a shelf, shot frontally in black and white against a solid backdrop. As exhibited, these works foretold the photographic practice treated in the rest of the small show: Ruscha went on to use such artless viewpoints to picture vernacular subjects, stripped of affect, in artist’s books such as Twentysix Gasoline Stations(1962) and Some Los Angeles Apartments (1965).

Among the pictures at the Gagosian in 2003 was a photograph of a can of spam. It was a sketch of sorts of Ruscha’s later painting Actual Size, which has “SPAM” in big type, the typeface from the can, and an actual size can of spam flying through space. It’s hilarious. It’s hard for me to place what I first saw when and where, but I likely saw Ruscha’s Spam can at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in the 1970s as a teenager, along with other artists who were playing with words and type – Jasper Johns I’m pretty sure among them. (I would normally give you an image, but I haven’t found any that I’m confident are freely shareable.)

I’m done with revisions to the new book, so I’ve let my brain off leash for the first time in a while and it’s been over sniffing at the art.

Ruscha’s L.A., so my roots, and also a goofball. In 1966 he mounted a camera in the bed of a pickup truck, photographed every building on the Sunset Strip, and published them all as a 25-foot-long foldout book. “Pop” or maybe “conceptual artist,” whatever, I’m not here to pick a fight. It’s his words that interest me.

Ruscha, who worked briefly in advertising (a handy explanation?) plucked words out of language and hung them on gallery walls.

Spam.

Later Wittgenstein

The key to later Wittgenstein (there were sorta two of him) is his oft-quoted linguistic bon mot – “The meaning of a word is its use in the language.” I love this, because it recognizes language as a fundamentally social thing – it’s us, in conversation, iterating as we sort out meaning, a rejection of an “essentialist” notion of meaning in favor of looking at how we actually use language.

This is what’s so intriguing about Ruscha’s use of words in his art. He would make these big paintings of a word – “OOF,” “SPAM,” “HONK,” or his later work when he expanded to whole sentences! “ALL WE HAVE IS NOW.”

I stand there. I look. I bring my language to the exchange, and try to understand Ruscha’s. Is it an exchange? Does it matter what the artist *meant* when he picked *that* word?

Wittgenstein defines the meaning concept with something he calls “language-games” – the contextual frame around the type of communication we’re involved in when we’re using words in a particular way. Ruscha made a new language-game, and treated it like an actual *game*. Rip a word out of its context and hang it on a gallery wall!

This is the magic of Scrabble. It’s like an afternoon at a Ruscha retrospective, words ripped one at a time from their context, an aesthetic built around game play but also the intricate relationships of text and meaning. “Emu!”

That is as quite a weave, and you pulled it off well

Thanks so much, Gerridh. I wasn’t quite sure I had it, but I’m trying to remember (to mix metaphors) that the blog is a sketchbook, and the only way to build the muscles is to push them.

Wittgenstein’s Tractactus was written in the context of logical positivism in the same vein as Whitehead and Russell’s Principia, based on the picture theory that language could directly represent the world. Korzybski in Science and Sanity, (General Semantics) refuted that with simple examples about how the map is not the territory. (Something good for Colorado River negotiators to remember). Wittgenstein was highly critical of his first work and later saw that language is a marvel-ous form of life itself and consists of numerous language games with meanings of words, phrases, propostions, having something like family resemblances to each other.

One of the most impressive insights I learned in phonology was that phonemes are abstractions, and that even babies early on pick up on those meaningful abstractions and no longer attend to actual phonetic signals. Think of the various acoustic signals that we immediately interpret as /t/ when in fact the “sounds” are actually quite distinct. carefully listen to the “t” sounds in top, stop, mat, little. Add the Cockney accent with the glottal stop on “little” for one more sound that literate people will call “t”. For most of us, the medial sounds of ladder and batter are the same. But once a child is literate, they hear two different “sounds,” meaning that they almost instantly convert a sound into the writing system. (on a side note, ask any English speak how many vowels English has, and they nearly all say 5, when English has at least twelve and in some dialects up to 14. Because vowels are sounds, not letters.) A wondrous talent, we humans have, in language.