Falling behind.

I was talking to Eric Kuhn Thursday (write a book together – bonded for life) who pointed out that the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center has started running its models for 2025 runoff. They don’t look good.

It’s way too early to think of this as a “forecast.” But they provide a feel for where we’re at now: Do we have a good head start? Are we already behind? The error bars are still huge, with a lot of upside potential, but we are already behind – 1.4 million acre feet below median for Lake Powell inflow.

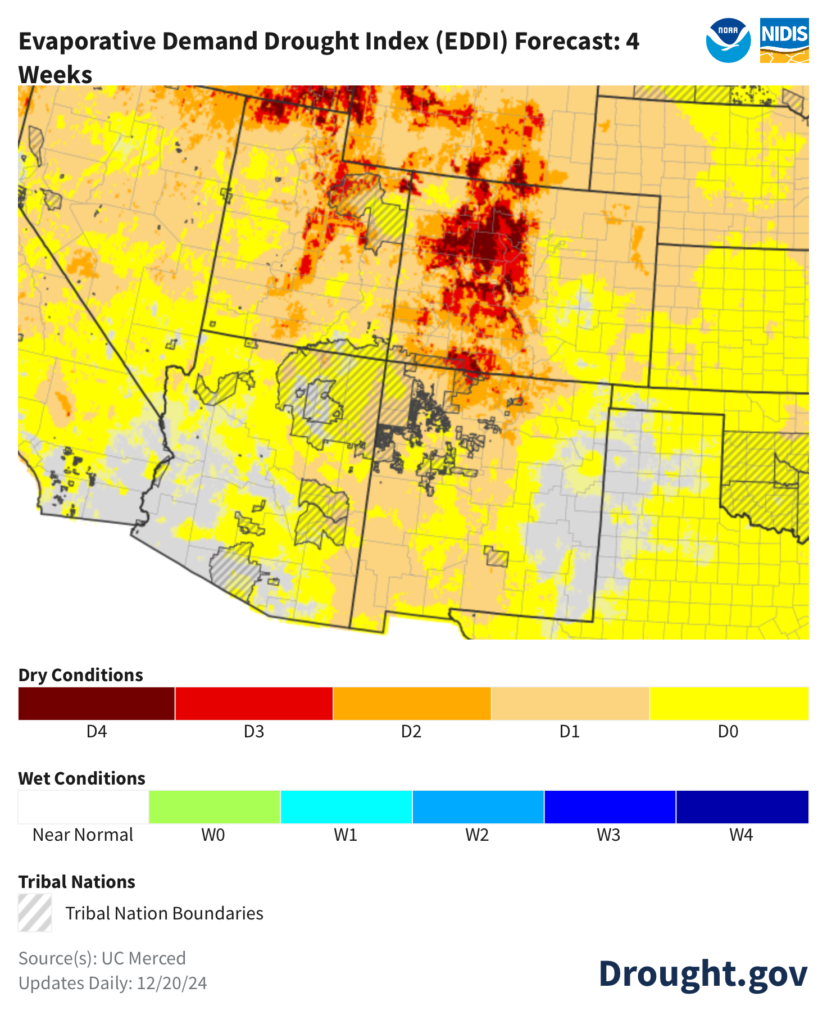

The current climate forecast headlights, which can at least dimly illuminate the next month for us, don’t look good. The US Drought Monitor folks publish an experimental forecast tool called the Evaporative Demand Drought Index (EDDI).

EDDI uses the federal Climate Forecast System model, an operational model to help gauge conditions over the coming months. CFS is then coupled with tools to estimate evaporative demand – not simply how much snow we’re going to get, but how rain and snow interact with temperature and atmospheric moisture, all of which play roles in the system that sends water from the snowpack in the Rockies to headgates and kitchen taps across the West.

EDDI says that over the next month, we should expect the CBRFC’s runoff forecast to go down, not up. We’re falling behind.

Why this matters

The obvious reason this matters is its direct relationship with this year’s water management. Will Powell and Mead go up or down? What does that mean for near term water supply?

But we’re also all playing multiple games of four-dimensional chess trying to anticipate how the near term runoff scenarios influence long term negotiations over Post-26 river management. One of my little projects right now is to step back from my normative angst (where “normative angst” == John’s super pissed off about the negotiators’ abject failure) to think about the deeper negotiation theory stuff going on.

John,

Tell me what you expect from negotiators’. Arizona seems to think that keeping Blue Mesa Reservoir empty will produce abundant CAP water. Colorado is saying what you are. There is no water to give. There is no mega drought, there is mega drying. The steady downward trend in the Basin will continue with the normal wet and dry year variability. The only hope for Phoenix and Tucson is to buy and dry some of the Imperial Valley.