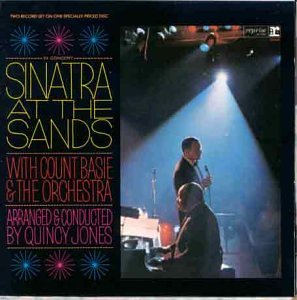

Sinatra, Basie, and Quincy Jones

I don’t remember how I stumbled onto Ernie Smith’s Tedium. All you need to know is that he wrote the definitive guide to why Butterfinger candy bars break so easily:

I’m always drawn to the structural integrity of candy bars. On the surface, they are often stacked, solid, as thick as a smartphone. (It must be the nougat.) But they break down easily, with only a minimum of outward pressure. Which is why it’s not a bad thing to put a smartphone in your pocket, but maybe not a Snickers.

One of the reasons I abandoned newspapering as soon as I saw a clear path was the stress – there was no silence. By this I do not mean the absence of sound – perhaps “silence” is not quite the right word – as the absence of freighted, weighty noise.

Smith had a piece this morning about the value writing about ideas that can “take up space… offer up points of conversation as alternatives to talking about the noise that constantly fills up our eardrums.”

If I had the writing chops, here’s where I’d go with this….

Your Moment of Zen

One of my favorite pop music tricks is a meandering misdirection in a song’s introduction, circling the main narrative before converging on it, the musical structure emerging slowly. Derek Trucks’ quiet wander into Midnight in Harlem on the band’s Everybody’s Talkin’ album is a current favorite. It makes me stop and listen. It drowns out the noise with a special quiet, commanding patience and attention.

The creaking door, the sinister footsteps, the wolf’s howl, before a ticking clock sets up the rhythm in Michael Jackson’s Thriller is canon here. I am riveted, peering from the first few bars into the song’s future, knowing what’s coming.

Sinatra at the Sands in 1966, the patter, the quiet Count Basie piano luring us into a drunk song.

Quincy Jones, amiright?

Sixteen years separate Sinatra at the Sands from Thriller, two of the towering works of American pop culture, both made possible by the towering talent of Quincy Jones, who died yesterday at the age of 91. I am listening to both this morning, and the musical structure Jones built to showcase the talent of both Jackson and Sinatra is a joy.

When I was a kid in L.A., learning how to write, I took repeated stabs at writing about pop culture and art, and I often wonder what might have happened if that path had more clearly opened up before me. I don’t regret the path I ended up on. It gave me a life of meaningful work. But it sure was noisy.

Look, I get that both Frank Sinatra and Michael Jackson are troubling characters. If I had the writing chops, that would add a richness to the narrative, another layer beyond the noise. Or perhaps that is the noise? The story of Frank Sinatra and Michael Jackson and Quincy Jones is deeply entwined with our nation’s troubled history of race. If I had the chops, I’d write about that, too. Maybe there is no way to avoid the noise.

For now, I’ll just play Thriller one more time before getting back to work.

Thanks for this piece. Quincy was a leader in the field. To add a little bit, Quincy and Jimi Hendrix went to my high school in Seattle. Quincy about 13 years ahead of me and Jimi about 4. Quincy donated a very large addition to the school for a gym and auditorium. The school has long been known for its music department that has won numerous competitions in city, state and national. Not including me. The largest ethnic group in the school is African American. Jimi killed it in Woodstock. A signature event in music and American history. Just watched a recap by a noted photographer of not published before photos.