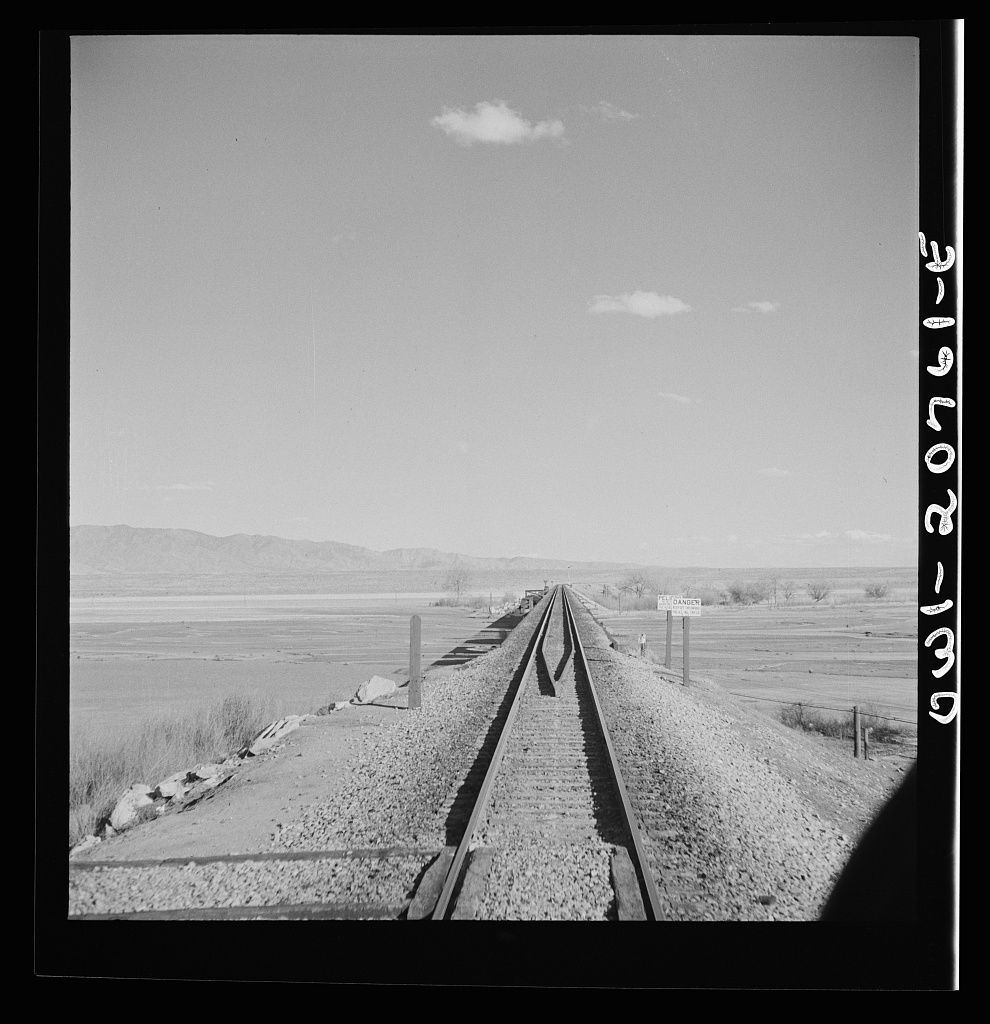

Belen AT&SF Rio Grande crossing, looking east, March, 1943. Note lack of trees. Jack Delano, courtesy Library of Congress

This Rio Grande crossing, just south of Belen, 30-plus miles downstream from Albuquerque, has changed dramatically since Jack Delano took the picture above in spring 1943.

The Bosque

I’ve stared at Delano’s picture often, because of the story it tells – a broad open river valley. It’s nothing like that today.

I pieced together some dirt roads and ditchbanks to visit the site on this morning’s bike ride. I had hopes of duplicating Delano’s picture, but the train traffic made standing in the middle of the tracks seem ill-advised. The picture to the right, facing the river looking east, should give you a feel. The Rio Grande here is now flanked by a magnificent cottonwood gallery forest, with low stands of coyote willow and salt cedar and some other stuff. We call it “the bosque.”

Looking at the picture last night as I was doing the map work to figure a sane bike route to get to the bridge, the date clicked: Spring 1943. In thinking about the modern relationship between human communities and the Rio Grande, 1941-42 is a dividing line – the last big flood years, the floods that drove the major changes in river management that created an ecological niche that the cottonwoods exploited in the second half of the twentieth century with full-throated glee.

Delano’s picture can be misleading. It wasn’t all treeless like that. The 1917-18 Rio Grande drainage survey, which is our best “before” snapshot of the valley, shows clumps of cottonwoods up and down the river. Following the 1941-42 floods, the federal Middle Rio Grande Project reengineered the main river channel with a series of sediment traps on the banks that were intended to push the river into a narrower central channel. In the process, they created ideal seed bed habitat for the cottonwoods to fill in the empty spaces.

The result is a linear cottonwood gallery forest more than 150 miles long. I’ve always called it “continuous,” but I just scanned the whole length using satellite imagery and found two short gaps. So “nearly continuous,” to add precision.

The bosque is often treated as one of the Middle Valley’s great natural treasures, and I don’t disagree. But “natural” may not be quite the right word.

Pecans

Belen High Line Canal, feeding pecan orchards in New Mexico’s Middle Rio Grande Valley. John Fleck, January 2024

Next stop: one of the most interesting climate change adaptation experiments underway in Middle Valley agriculture.

Past the railroad bridge, I found a ditch crossing and peeled away from the river toward the sand hills to the east, winding through the small farms of Jarales that make this stretch of the valley a lovely exemplar of the “ribbons of green” we talk about in the new book. Nearly all the farms were less than 10 acres – non-commercial, “custom and culture” agriculture, mostly alfalfa or other forage crops, lots of horses. Dodging the one busy highway the best I could, I veered into a neighborhood and under the interstate, where the road kicked up to a geomorphic bench in the sand hills maybe 30 feet in elevation above the nearby valley floor.

The pecans are in the distance in the picture to the right, though you can’t really see them. I was on relatively unfamiliar ground, and was cautious in my interpretation of the “No Trespassing” signs on the ditchbank road. It’s land that was once scrubland just like the land in the foreground. Now it’s irrigated with water from the ditch in the picture, to the tune of more than 1,000 acre feet per year. (We don’t know exactly. We don’t meter this use of water here.) There was a lot of controversy nearly 20 years ago when the land was brought into production. Critics (included regular Inkstain commenter Bill Turner, who was on the MRGCD board at the time) argued it wasn’t entitled to irrigation water from the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District’s ditches. I’m not going to relitigate that argument here. Those objecting to serving the land with MRGCD irrigation water lost. Now the land is home to a fascinating experiment in climate change adaptation.

With a warming climate, the optimal range for pecans has moved north. (UNM Water Resources Program grad Tylee Griego took a deep dive into the pecans’ migration here.)

We have seen a century of failed efforts to foster a commercially successful crop in the valley – wheat, tomatoes, sugar beats, pinto beans, tobacco (!). Pecans are the latest, and rather than climate change making it harder to grow stuff, in this case it has made it easier. By increasing irrigated acreage in the valley. We usually think of agricultural climate change adaptation as “crop switching,” not “crop adding.” In addition to the big orchards by the river, the latest USDA CroplandCROS dataset, which uses satellite data and algorithms to identify crop types, is showing more pecans in small patches across the valley. I don’t full trust CroplandCROS – it gets a lot of pixels wrong ’round here, unfortunately. But this just means more bike rides needed to “ground truth” my blog posts. This is a part of the valley I don’t know as well, so fun ahead!

As I was riding through Jarales this morning and writing this post in my head, I was playing with the theme suggested by the two forests – each spread across a niche created by human alteration of the hydrologic system. Not sure it quite works, but I’ll leave it here.

A note on Jack Delano

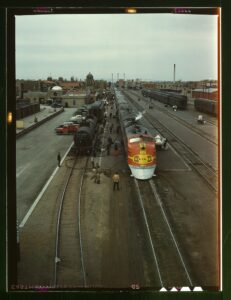

“Santa Fe R.R. streamliner, the “Super Chief,” being serviced at the depot, Albuquerque, NM. Servicing these diesel streamliners takes five minutes”. Jack Delano’s original caption. Courtesy Library of Congress

Jack Delano’s 1943 trip through New Mexico is worthy of note.

Delano, born Jacob Ovcharov in Ukraine, was one of the Farm Service Administration/Office of War Information photographers whose work dominates our visual understanding of the 1930s and early ’40s in the United States. His photographs of the AT&SF rail yard in Albuquerque, taken on the same spring 1943 trip that he took the Belen railroad bridge above, represent a remarkable documentation of a moment in time, as freight bustled through Albuquerque in service of the war effort.

We tend to think of the classic FSA photography as “documentary” work of the highest order – which it was. But it also was government propaganda – artists paid by the government to tell particular kinds of stories, and share particular kinds of messages.

Much of the classic visual vocabulary of the FSA pictures – think Dorothea Lange – is very much black and white. But with the development of Kodachrome in the 1930s, photographers of the period were beginning to shoot in color too. Most of Delano’s Albuuquerque pictures are in black and white, but his color picture of the Albuquerque rail yard, taken from the Lead Avenue orverpass circa 1943, is a classic.

John

Governor of Isleta showed me a photo of Rio Grande Valley view west from Laguna from 1880s. Not a tree in sight.

John, I’m Cullen Woods from Manzano del Sol. Retired and living in eastern OK.

I have always enjoyed our visits over the years. And your article has brought so many memories back. Thank you.

In the 90’s I did a lot of mountain biking in the Bosque in Socorro. And while we were in ABQ found trails from Sandia to Isleta. Great memories. Thank you for sharing your mom and dad with me.