On my penultimate bike ride of 2023 Friday, I turned west on Bobby Foster Road in Albuquerque’s southwest valley, wandering past junk yards and Ace Metals: “THE BEST PRICES IN ALBUQUERQUE For: Steel, Iron, Junk Cars, Tin, Appliances, Aluminum, Copper, Brass, Batteries, Stainless Radiators, and Catalytic Converters”.

With my current loosey-goosey career, it’s easier for me to ride on weekdays, but it was the first time I’ve ridden the junkyard neighborhood on a weekday. Totally different. Groups standing around old wrecked cars talking parts, a crane picking and stirring the junk pile at Ace, a mail truck making the rounds. Human stuff, people living their lives.

My “geography by bike” is mostly a self-indulgent hobby, loosely linked to “exercise” and “goofing.” But the occupational hazard arising from a life as a writer is that I’m always writing, always seeing the things around me through the mental exercise of imagining how I might write about them.

I’m always writing.

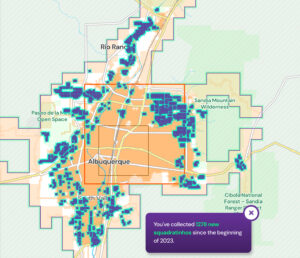

Blue-green squares are places I rode this year that I’ve never ridden before (at least since I started GPSing my rides 15 years ago), as measured by a grid of squares about 1/6th of a mile on a side.

This came in handy over the last year as Bob Berrens and I were writing the manuscript for our forthcoming book Ribbons of Green, about the history of Albuquerque’s relationship with the Rio Grande. Everywhere we were writing about, I have ridden. I ride everywhere, by which I mean trying to find new places that I’ve not visited before. I have old standards, rides I love to return to again and again. But my favorite thing is to ride down a street, or ditchbank, that I’ve never ridden down before. (GPS and mapping software help in this regard. Did I mention that it’s a self-indulgent hobby?)

The thing about riding a bike is that you largely are riding through human-created spaces. It’s a window into what the French philosopher and sociologist Henry Lefebvre called the social production of space, and the joy for me in visiting places like the junkyards off Bobby Foster Road is thinking about the structure of the human lives that are forever producing these spaces.

My pursuit of new places to ride – it’s a bit hard core, see the map on the right – has encouraged an increasingly complicated grappling with what we might call “the commons,” or what, in a much more broad sense, the political scientist Bonnie Honig has called “public things.” My interest in the commons is longstanding. It’s at the heart of my book Water is For Fighting Over, which drew heavily on the ideas in Elinor Ostrom’s Governing the Commons for its conceptual superstructure.

Ostrom and those bouncing around her were/are focused – properly! – on the commons in the context of “common pool resources” – stuff that we all need, that we all kinda share, but if I use too much there’s not gonna be enough for you, etc. Such as water, which is what got me invited to this party.

“Public things” is a broader category. In her book, Honig is careful not to define it, preferring to work the question through by way of example:

For example, a public thing may not be publicly owned but is public insofar as it is subject to public oversight or secured for public use.

So public streets are, for sure, a public thing. But how do we know which streets are “public?”

Lagunitas Lane and a place to pee

I stumbled onto Honig’s book via a link in an essay by Shannon Mattern about public drinking fountains. If you ride your bike a lot, as I do, you think about public drinking fountains and public toilets. There are few, which is why the glorious public infrastructure at the new Valle do Oro National Wildlife Refuge in Albuquerque’s Mountain View neighborhood stands out.

This is the broader sense of “public things” as the stuff that provides what Amartya Sen defines as “capability” – the underpinnings of our ability to live the lives we choose, meeting our preferred goals and desires.

Albuquerque’s new International District Library – the library Lissa and I have chosen as ours, a regular Saturday outing – is a great example here of a public thing. Not only is its architecture, like the Valle de Oro visitors center, gloriously enabling, but it has public computers and public bathrooms. This is a pretty flimsy floor for the Sen-style “capability” of our unhoused neighbors clustered in the neighborhood around the library, but anyone can use the computers to access the things on the (“quasi-public”?) Internet you need to engage in Sen-capability stuff, and there is a steady flow of people going to the special desk the librarians have set up in the library’s back corner to manage the bathroom key.

Some years ago, when Valle de Oro was still in the early phases of its transition from former dairy farm to wildlife refuge, my riding buddy and I had occasion to try to wander into the newly “public” (that word again!) property from the neighborhood on its northwestern edge. We turned down Lagunitas Lane and, when the pavement ended and turned to dirt, kept riding past the “County Maintenance Ends” sign.

As we noodled south looking for a way to get into the wildlife refuge, a car approached slowly, the driver rolling down the window. “You know this is a private road,” they said, snippy. We smiled politely, thanked them for telling us, and kept going in search of a permeable gate to get onto the refuge.

In the five years since that encounter, I have always assumed the driver knew whereof they spoke. It has not stopped us from from riding down Lagunitas Lane, because the gate remains permeable, it’s a great place to get into Valle de Oro, and exploring the boundaries between “public” and “private”, the slippery notion of “trespassing”, is a big part of the exercise. But I was always wary of another encounter with Snippy Driver. “Trespassing” carries both social and legal costs.

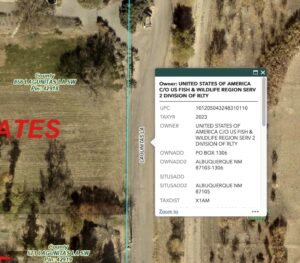

But a look at the county property maps this morning suggests that this stretch of Lagunitas Lane is, in fact, public property, by which I mean owned by the federal government, so me! And you, too (some terms and conditions may apply).

I do not mean to equate my need for easy access to a wildlife refuge for purpose of bike riding escapades to the needs of our unhoused neighbors to apply for a job or pee. One is clearly more foundational to what Sen is talking about than the other, but it’s a continuum worth exploring.

The junkyards off of Bobby Foster Road

The Ace Metals road (I know, it’s been a while, we’re back to the bike ride I started this post with 1,100 words ago) is part of an area marked off in red on the maps I use for bike ride planning. They’re based on Open Street Map, a Wikipedia-like mapping site. (Open Street Map is a public thing.) Red means “industrial area”, and it also usually means “John can’t ride his bike there.” It’s also not on Google Street View, another “can’t go there” ride mapping clue. But I thought I remembered my riding buddy saying he’d done it, and I was in the neighborhood because I’d been riding in the neighboring flood control channel (Public! But maybe not for bike riding?), so I gave it a look.

It was a weekday, and the first thing I saw was a mail truck heading down the road. The U.S. Mail, a public thing if ever there was one! So off I went. A couple of guys standing talking by the side of the road outside one of the junkyards smiled and waved a “Hi”, which always feels so very public, a shared space thing.

At the far end, the road dead-ended with a gate into the last business. I eyed, as one does, the fences looking for a way through to the neighboring railroad tracks (railroad tracks regularly pose the “public or not” dilemma, these I decided “not”).

I rode back, got the obligatory Strava mobile phone picture of Ace, and rode on out of the neighborhood past the angry pit bull guard dog behind the fence of the last junkyard on the left (angry pit bulls a definite “not public” signifier).

Here’s the thing. A look at the county maps shows the whole road, from the pit bull to the gate a half mile down, is private property. I’m not savvy enough with the available maps to know about easements and maintenance agreements and the like, but it was a fun place to ride my bike.

A year on the bike

Much of my mental focus in 2023 was finishing the manuscript of Ribbons of Green, which was (and remains) an all-brain activity. So when I rode, which I do (373 hours on the bike, an average of a shade more than an hour a day, 3,173 delightfully slow old guy miles), I toured the landscape of our book.

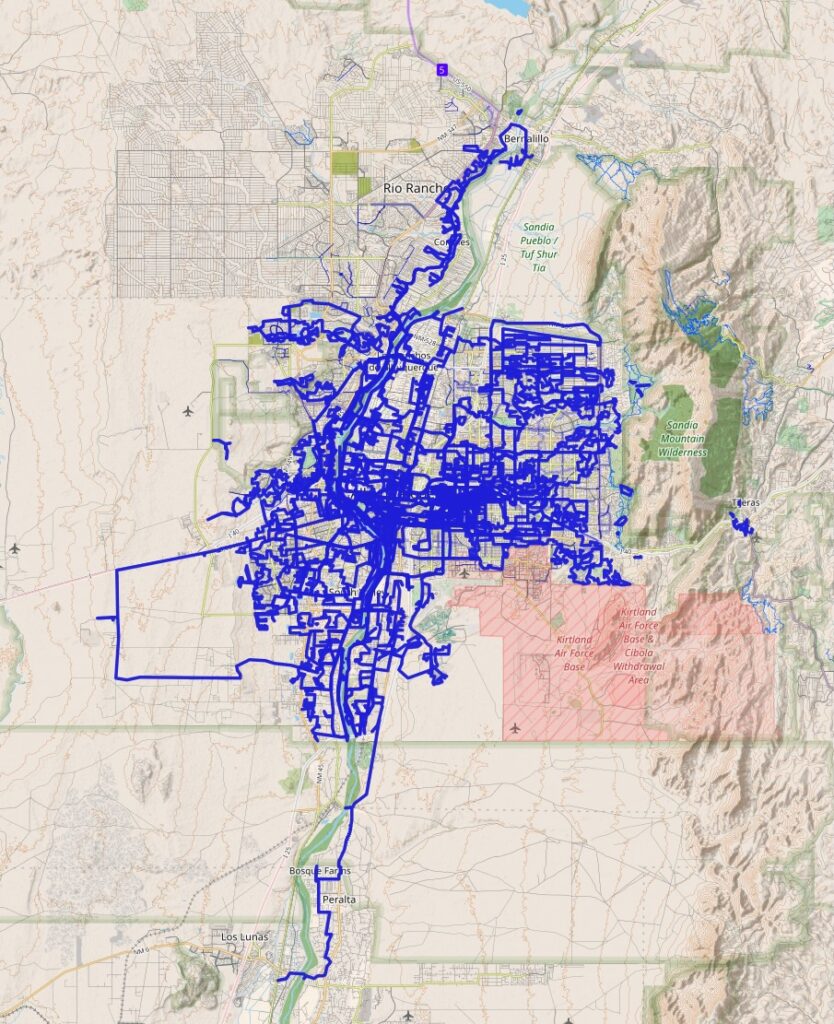

My 2023 bike rides, h/t to the amazing Stan Ansems at Statshunters

I covered the whole Rio Grande Valley floor, from Bernalillo in the north to Los Lunas in the south, excepting the land of the indigenous Pueblo communities, which bear profound public/not public implications. I basically rode the entire “study area” for the book, which is about the interplay between the Rio Grande and the greater Albuquerque community.

I also spent a good deal of time exploring up out of the valley, parts of the city I’d not yet ridden. My goal is to ride everywhere, where “everywhere” involves a map grid of the greater metro area, squares that are about 1/6th a mile on side. Some of these neighborhoods are frankly not as interesting as the crazy spiderweb of river, levees, ditches, and flood control channels that define the hydraulic infrastructure I mostly write about.

But it’s all interesting! No place is uninteresting, junk yards least of all.

If I’m reading your last map correctly, you haven’t riden NM-313 from Alameda to Bernalillo or farther north (though maybe the route number is different farther north.) Hard to believe. Ah, when I double-checked I now see this is only your 2023 rides, so no doubt you’ve ridden that public highway in earlier years. There’s a (mostly) wide shoulder south of Bernalillo. A very nice ride through the fields of the pueblos.

WOW! These rides are an accomplishment in-and-of itself! I’m sure this will be an equally immersive read.