People board a city bus in downtown Albuquerque. Walter McDonald, 1969, courtesy Albuquerque Museum, object number PA1996.006.036

I have devoted an inordinate amount of time over these last few months thinking about two things: finishing the book, and dreaming about the dreamy freedom of my life after we handed over the manuscript to the University of New Mexico Press.

The book work, finishing the manuscript of Ribbons of Green: The Rio Grande and the Making of a Modern American City, which Bob Berrens and I have been working on for the last three years, has been a joy, but an intense one. We’ve been burning pretty hot. It’s the most ambitious project I’ve ever attempted, out at the edge of my skills.

My dream for The Time After was to dive into Robert Caro’s The Power Broker, a doorstop of a non-fiction tome. I still have to finish my semester’s teaching, and then Lissa and I booked a cottage for a few days in a remote, undisclosed location. My thinking was that Caro’s book – the subtitle is Robert Moses and the Fall of New York – would sweep me away to a new place and a different set of ideas.

Oh, John, you sweet, sweet child.

A water book? A city book?

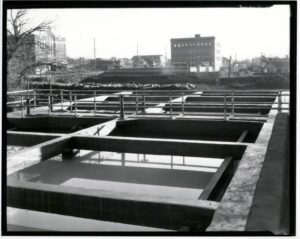

Water basins at the water treatment plant near downtown Albuquerque. Brooks Studio, 1930. Courtesy Albuquerque Museum, object number PA1978.152.373

A friend who’s been living with my yammering about Ribbons of Green for those three years asked me over the weekend when I realized it was a city book. “I dunno, three weeks ago?” I replied.

It was reasonable to think I was writing a water book. That’s what I do. My friend, who’s been listening to me talk about it week after week, month after month, year after year, as we rode our bikes across the greater Albuquerque metropolitan area’s vast river valley, had known long before I had. Bob and I have written a city book.

This is, in retrospect, unsurprising, a return to my roots.

My first paid writing gig, in the spring of 1981, involved (among other things) sitting in Walla Walla, Washington, city council meetings trying to understand the functioning of a municipal government. I read proposed ordinances and talked to the mayor and listened as traffic engineers explained the decision process for installing stop signs and traffic lights.

I was trying to figure out how a city worked.

A couple of stops down the career track, I was sitting in the Pasadena, California, city hall, still trying to figure out how a city worked. Pasadena had a water agency. What’s up with that? In understanding a community, I came to realize, I could start with its water.

Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses

Chatting at a pub a couple of years ago with two water/planning students, I inadvertently won brownie points with a casual reference to “eyes on the street.” It’s a catch phrase from Jane Jacobs, who wrote The Death and Life of Great American Cities. I wasn’t trying to show off! Jacobs is in the water I’ve been swimming in my whole career, the idea that cities need to be treated as complex, emergent things. Moses, Jacobs’ bête noire, carried with him the Progressive Era optimism for rational planning by smart men. Moses built expressways. He didn’t give a shit about eyes on the street.

Ribbons of Green didn’t start out as an attempt to grapple with the contradictions and conflicts between Progressive Era enthusiasm for central planning and the messy realities of the evolution of a city, but that’s where we ended up.

Albuquerque emerged from the same early 20th century Progressive Era thinking that spawned Moses. To build a city, the Progressives needed to solve the problems posed by building that city on a river valley floor.

“Flood control, drainage, and irrigation” is a leitmotif in the book – the driving motivations behind the project needed to build a city here. But the smart men of Albuquerque’s Progressive Era management never accumulated the power Moses did, instead crashing headlong into the messy realities of emergent city-making Jacobs described. Those messy realities are the subject of Ribbons of Green.

Crucially for our book, it was always water management in service of city-making. My old realization that to understand a community, I could start with its water, seems to fit. So definitely a city book?

Definitely a water book

Yeah, but the city – a linked urban/surbuban/peri-urban/rural collection of communities stretching 160 miles along the Rio Grande Valley – is built now. It is, à la Jacobs, forever emerging, never done. But as climate change saps the Rio Grande’s flows, throwing into ever sharper relief the community values both shared and conflicting, what shall we do?

The water management institutions we built to create a city, the ones we describe in the book, remain the ones we have available to answer that question.

So definitely a water book.

Nice story. About the town in the river valley, what now? And the rest of the southwest?

I believe that city bus is the same (or perhaps slightly newer) model as the one Rosa Parks was arrested on. Regardless it’s an iconic photo for that time period.

Ah-ha moments happen when they are least expected.

I enjoyed the telling of your realization. As always, I learn from your posts.

Get the book done. I want to read it.

Rhea

Love the bus. My son Adam did a short file about 20 years ago called Drive in which he used an ancient bus that we found at Rip Griffin’s in Moriarty. There is also one at the east end of Tiguez Park on the west side of the 120+ year old terrone house .

Great story, and thanks for commenting, and for sharing a great story. The busses used in Montgomery, AL, at the time Rosa Parks sat down for justice were purchased as surplus busses from the City of Terre Haute, IN.