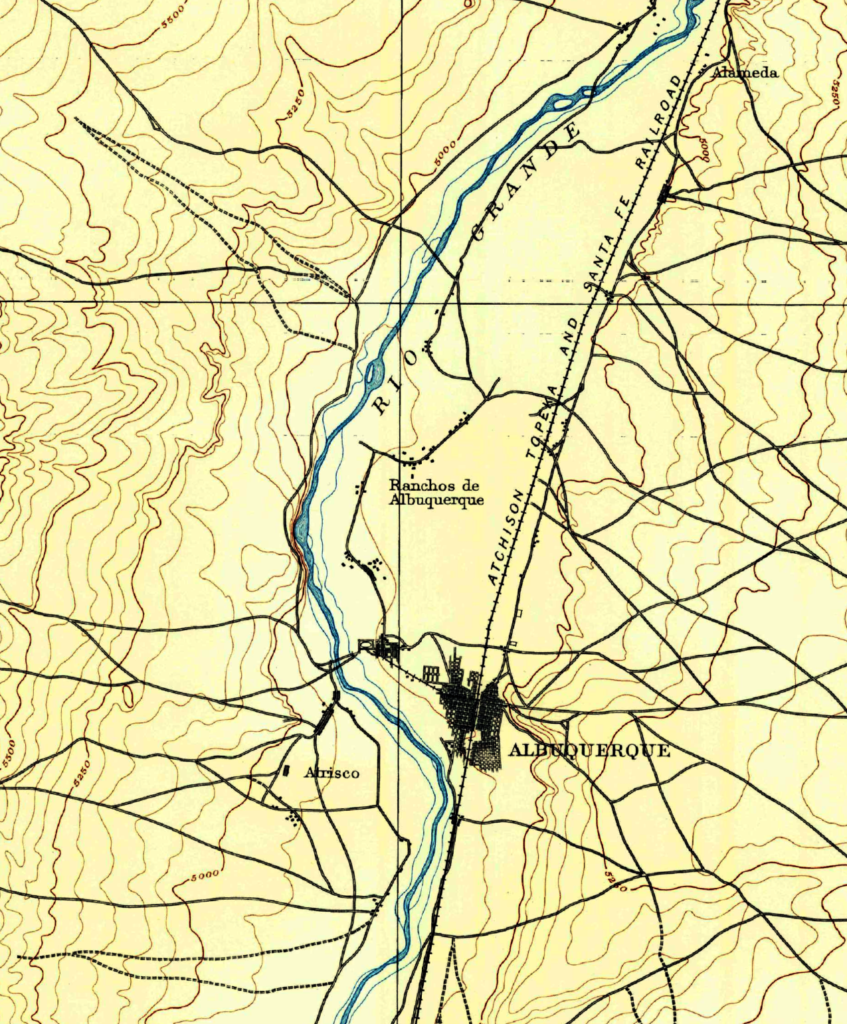

I’ve been fiddling with some of the maps we’ll be using for our book Ribbons of Green: The Rio Grande and the Making of a Modern American City, trying to think about how to use this 1888 topographical map of Albuquerque and its surroundings.

It may work best unadorned – a river, a railroad, and a city in the making.

They came in that order, each creating the conditions that enabled the next. The Rio Grande has been here since time immemorial. We (the “we” of this book is complicated, but grant me the word for now, we can debate its applicability later) built villages around it, and the AT&SF drove west until it hit the river, then turned left to follow its amiable grade south before lunging west again toward the riches of California.

Spandrels of Duranes

With the end clearly in sight (the two authors and our fearless reader doing final read-throughs and redlines over the last week), we’re wrestling with one final disagreement.

It’s a writerly bit of business in the book’s conclusion that I wrote early on (you have to have some sense of where you’re headed), invoking “the spandrels of San Marco”, a literary flourish from the evolutionary biologists Stephen J. Gould and Richard Lewontin.

Their metaphor was architectural – the “spandrels of San Marco,” gorgeous mosaics found in the ceilings of St. Mark’s Cathedral in Venice. The mosaics are purposeful, they argued in 1979 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. But the spaces in which the artists place them, curved corners filling spaces between architectural arches, are not.

“The design is so elaborate, harmonious, and purposeful that we are tempted to view it as the starting point of any analysis,” they wrote. “But this would invert the proper path of analysis. The system begins with an architectural constraint: the necessary four spandrels and their tapering triangular form. They provide a space in which the mosaicists worked.”

It’s in the midst of a passage on the Duranes Ditch, a lovely bit of green flowing through neighborhoods of Albuquerque’s North Valley. It would be hard to imagine designing a more elegant city park – long and lean, shaded with walking paths along a brook through 21st century neighborhoods, flowing green and cool during the hot desert summers.

Like the spandrels of Gould and Lewontin, the Duranes seems so elaborate, harmonius, and purposeful that it’s tempting to view it as the starting point for our analysis. But that would be wrong.

The Duranes, laid down in the 1700s and preserved as the community chose to create a Conservancy District to build levees, drain the swampy valley floor around Duranes, and consolidate the Middle Rio Grande Valley’s irrigation ditches, is one of our spandrels.

Consider Philip Harroun’s 1895 description of the Duranes: “Duranes ditch heads 3 miles above the old town of Albuquerque, passes below the town, and tails about 1 mile further down…. It has a common brush dam diverting about 11 cubic feet per second when at full capacity.”

Hidden behind the simple hydrologic description from Harroun, a U.S. Geologic Survey scientist who surveyed the valley’s irrigation works in the 1890s, is a rich, complex, and enduring water institution.

Hidden behind the simple hydrologic description from Harroun, a U.S. Geologic Survey scientist who surveyed the valley’s irrigation works in the 1890s, is a rich, complex, and enduring water institution.

It is a book about a community’s relationship with its river – Rio Grande shaping Albuquerque, and Albuqeurque shaping Rio Grande in return. In much the same way you cannot understand evolutionary biology other than a complex and ongoing interaction among organisms and their environment, we cannot understand Albuquerque absent an understanding of this complex, ongoing relationship of river and people. Our spandrels, the Duranes and the like, seem so purposeful, so meant to be, that it is hard to step back and understand the mix of path dependence and contingency that got us here.

The argument against the spandrels passage is that it may be a bridge too far, too much of a diversion at a crucial point in the narrative. It’s a tricky detour from the narrative flow, a test at the edge of my writerly chops. I can see this argument. The argument in favor of spandrels is that it’s an incredibly useful metaphor for what we’re trying to accomplish. I can see this argument, too. I wrote it!

We’ve got a couple more days until we hand the manuscript over to the University of New Mexico Press, and one last problem to solve.