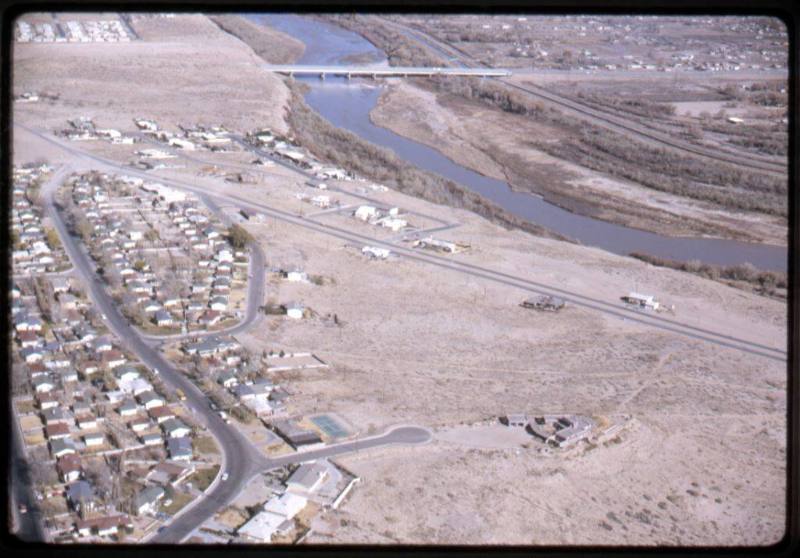

The interstate bridge being built across the Rio Grande, Albuquerque New Mexico, 1969, photo by Walter McDonald, courtesy Albuquerque Museum

Breaking out of my old “water policy writer” habits is hard.

The bridges of Albuquerque are helping.

Counting and Measuring

Prepping for an appearance on this Friday’s New Mexico In Focus on NMPBS, I’ve spent a bunch of time the last few days digging through agricultural water use data. (Spoiler alert: Ag water use has been declining in New Mexico for decades. Climate change adaptation is happening. When people have less water, they use less water.)

That’s long been a staple of my water policy writing – USDA NASS, and Cropscape, my beloved USGS Water Use in the United States data series, and on and on and on. You can’t manage what you don’t measure, amiright?

But our new book Ribbons of Green: The Rio Grande and the Making of a Modern American City, has me staring down the limitations of approaches I’ve used for so long.

Bridges

My coauthor Bob Berrens and I are deep into bridges right now. The literal physical objects that get you from one side of a river to the other. You can’t build a city on a river valley floor without confronting the collective action challenge of bridges.

Who builds (read “pays for”) them? Where do you put them?

In the 1920s, people in Albuquerque engaged in political struggles between neighborhoods that wanted bridges. Sixty-seventy years later, there were political struggles based on communities that didn’t want them.

Defining “water policy”

Bridges are not the only example of our attempt in Ribbons of Green to embrace an expansive definition. We’re writing about parks and recreation. We’re writing about evolving cultural relationships with the Rio Grande, including deep and diverse relationships with the act of irrigating and growing food. We’re writing about trees, and fish.

I’m reading Rudolfo Anaya right now. His characters go down to the river. That’s admissible evidence.

Establishing parks, and building bike trails, helps shape a community’s relationship with the river. That’s water policy.

Building fences to keep kids from drowning in irrigation canals helps shape a community’s relationship with the river. That’s water policy too.

Protecting wetlands? Water policy.

Regulating waterfront development (either encouraging it or prohibiting it)? Water policy.

Cutting down trees along an irrigation ditch to conserve water (or leaving them there as shade for the ditch walkers)? Water policy.

Fishing rules, canal trails, historic preservation and commemoration of the old canal headings at Atrisco? Water policy.

All of these things have a common characteristic: they reflect the tradeoffs we must make, the often competing and conflicting values we must articulate, things lying at the intersection of economic resources, ecological resources, and public infrastructure that define what Albuquerque has become as a modern city.