Out for an early walk this morning to the Rio Grande, we found a river settling nicely back into its main channel after a couple of months during which we allowed it to play a bit. Since April, the river’s been up and out of the 600-foot wide channel dug for it in the late 1950s, a gentle frolic through the woods – our “bosque” – that flank it through Albuquerque.

But it’s July 1, so play time’s over, as the river’s managers have throttled the river’s flow. In the last week, the river’s dropped from ~4,000 cubic feet per second at Albuquerque’s Route 66 bridge to 1,240 as I write this.

Rectifying a Flood Menace

I’m playing with language here. One of things I’m thinking hard about as I write the new book about Albuquerque’s relationship with the Rio Grande is the words we use to describe our river. For a good chunk of the time we’re looking at, from the late 1800s through the mid-1900s, “flood menace” was an incredibly common phrase.

“If the river breaks north of Albuquerque, it will certainly endanger the downtown district,” Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District chief engineer Hubert Ball explained in this 1947 newspaper account of a (radio? TV?) Sunday talk show.

For decades, the Rio Grande had been slowly “aggrading”, dropping sediment and raising its channel above the growing city on the valley floor. The flood of record in the modern era, in 1941, brought water in the Rio Grande’s main channel four or five feet higher than downtown Albuquerque. The levees that year barely held.

The Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District was formed in 1925 in large measure to create a framework for Albuquerque’s collective action to fight the flood menace. But it quickly became clear that the effort was a failure. The newly built levees were not enough, and the river’s bed kept rising. (As an aside, one of the chief reasons it was failing was financial – the District was perpetually broke. Subject for another blog post, and many chapters of the book.)

In 1947 (the year the KOB speakers agreed that the Rio Grande was a “flood menace”), the Bureau of Reclamation and Army Corps of Engineers, encouraged by local communities, offered up a plan. It basically amounted to a federal takeover of management of the river, with federal $$$$ to back it up.

The language they used to describe the project is super interesting. In addition to building a network for flood control dams on the major upstream tributaries of the Middle Rio Grande, the offered a plan for what they called “channel rectification”. To rectify, per OED, is “to restore to a normal or proper condition”. Much like the agency’s name itself – “Reclamation”, to “reclaim” – the language implies a vision of nature where human engineering prowess could correct the flaws of the natural world.

Training a River

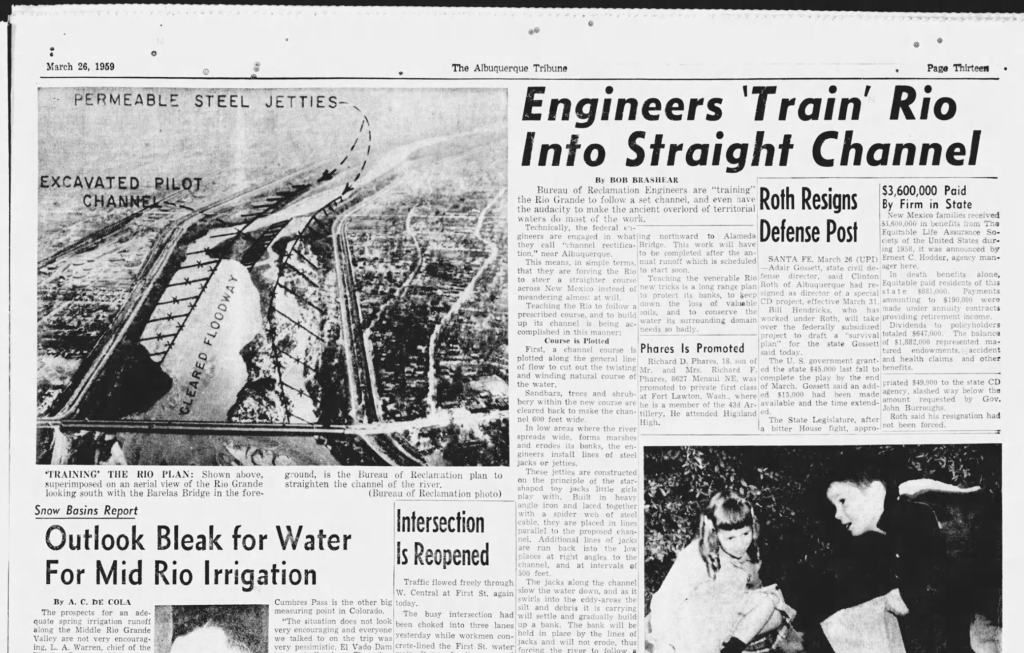

It took more than a decade of institutional wrangling for the channel rectification work to get underway (Again, subject for another blog post some time, or read our book as soon as we finish writing it! Spoiler alert: paying for it was again the key.). In trolling newspaper archives, I stumbled across this gem of an explanation, by Bob Breshear in the Albuquerque Tribune, March 26, 1959.

Engineers ‘Train’ Rio Into Straight Channel

Bureau of Reclamation Engineers are “training” the Rio Grande to follow a set channel, and even have the audacity to make the ancient overlord of territorial waters do most of the work.

The idea was to dig “pilot channels” at key locations, with “jetty jacks” along its bank lines – tangles of 16-foot steel beams so named because they look like childrens’ toy jacks – to capture sediment and anchor the river’s banks. “Sandbars, trees and shrubbery within the new course are cleared back to make the channel 600 feet wide,” Breashear explained to his Albuquerque Tribune readers.

In low areas where the river spreads wide, forms marshes and erodes its banks, the engineers install lines of steel jacks or jetties.

Can’t have that!

In the book writing, I’m wrestling with a challenge – the a desire to avoid cheap anthropomorphizing of the Rio Grande while at the same time recognizing that it’s a central character in the book. Brashear felt no such constraint. The engineers, he wrote, were “teaching the Rio”.

The Oxbow sandbars

There’s a stretch of river just downstream from where we were walking this morning, at the foot of bluffs on Albuquerque’s west side, where the Rio Grande is now doing the teaching.

It’s a spot where Reclamation dug an aggressive pilot channel in the summer of 1959, creating a new path for the river and stranding an old oxbow meander curling along the edge of the bluff, which remains as the best river-connected wetland for miles. (The story of the Oxbow gets a whole chapter in the new book.) In the low flows of 2020 vegetation, mostly willows, began growing on a sandbar adjacent to the Oxbow, pinching Reclamation’s 600 foot wide channel in half. With a couple of low flow years, the vegetation has become well established. With this year’s high flows, the water got up over the sandbar, but when we were out last Sunday, it looked like the willows we’re holding.

It’s a pattern we’ve been seeing for a while in the stretch of river south of Albuquerque, as sandbars grow and then become vegetated within Reclamation’s old 1950s-era 600 foot channel. The Rio Grande is, on a small scale, mimicking what it once did more broadly as it meandered down the valley. We’re increasingly seeing the same thing here in the Albuquerque reach. River’s gonna do river things.

I’ll head back out to the Oxbow next week now that the water’s down, and report back on the results.

The Book

The book is Ribbons of Green: The Rio Grande and the Making of a Modern American City, by John Fleck and Robert Berrens, to be published as part of UNM Press’s New Century Gardens series. As soon as we finish writing it.