A “long lot” in Albuquerque’s Duranes neighorhood

Sunday’s bike ride book research took us up along the old Duranes ditch, through Albuquerque’s near north valley. The landscape is still wearing its winter coat, but it’s clearly dusting off its leaf-growing apparatus and getting ready for spring.

We stopped to get a look at one of my favorite old farm fields, on Los Luceros Road. If you don’t count parks, it’s likely the largest irrigated parcel left in Duranes, about an acre in size. But look at the picture. Look at its weird shape – 600 feet long, maybe 75 feet wide

Long lots and “partible inheritance”

A guiding theme of our new book is the notion that institutions shape landscapes. By “institutions” here, we mean rules. The government agencies, the more common thing we talk about when we talk about “institutions”, are relegated to an important but secondary role – they are the tools we build to carry out the rules. So you’ve got to start with the rules.

The rule that drives the shape of this long narrow lot on Los Luceros is “partible inheritance”, a practice rooted in Spanish law of dividing land up equally among heirs to a piece of property. You can’t write Johnny out of the will because he joined the circus to pursue his dream of becoming a clown. Johnny still gets his share of the land when Mom and Dad are gone. And, importantly, because its value is connected to his ability to irrigated, Johnny and his siblings each get a narrow piece of land, connected on one end to the ditch.

Partible inheritance – “partición de bienes” – inevitably led to a bunch of “long lots” in the midst of urban Albuquerque.

Long lots and Albuquerque’s urban form

The urban development of Albuquerque was passed through the institutional funnel of partible inheritance.

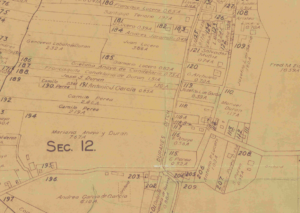

You can see it in the map to the right (click to blow it up), showing the land ownership structure of the old village of Los Duranes circa 1927.

Long lots helped to establish a distinct agricultural landscape, as small family-owned subsistence farms gave way to work in the wage economy after the arrival of the railroad in 1880.

The long lots and the ditches influenced the layout of roads and paths, and which mostly (as in Duranes) run parallel to the ditches, sharing the high ground path the ditch builders chose for the first and most crucial piece of Albuquerque’s urban infrastructure.

Partible inheritance also resulted in fragmented land ownership, which shaped the urban growth and development patterns of Albuquerque.

The primary large parcels available to the early 20th century city-builders were the ones not subject to the “long lot” phenomenon. (Reader warning, I’m getting arm wavy here, but this is the hypothesis.) These big chunks of non-long lot land were mostly swamps and riverside woods, and that’s where you find the wave of suburban home building in the middle third of the 20th century. I think.

John: You need to understand the historical and cultural significance of long lots. They are virtually ubiquitous the world over. They are proof of agricultural use of the land. They are universally sloped with a high end and a low end. The high end is always on a source of water and the bottom end of the long lot is always on a road leading to a mill. Water is distributed with the aid of gravity as is harvesting. The early Dutch maps of Manhattan and Long Island show the farms were long lots. See also the shape of lots in the vicinity of Three Rivers, Canada. The lots along the Ayia Marina – Pomos Coastal Plain aquifer of Western Cyprus are all long lots. I did the hydrology of this coastal plan aquifer. In New Mexico, a former Frontier Colony of Spain the long lots are referred to as minifundio lots. The long lots developed out of necessity and efficiency. It was easier, used less energy, and more efficient to plow longer furrows with less turns of the plow train. The plow train comprising several draft animals, the stick or old moldboard plow and the farmers could be 30 feet long and unwieldy to turn to plow another furrow. The plow path was a broad “S” in form. The plow train was always turned in “headland” of the lot. Each lot has a headland at each end of the minifundio. The moldboard plow wast patented in the United States in 1803 by Thomas Jefferson and his original plow is in the Monticello Museum, though not well displayed. The minifundio was a fortuitous shape because it also allowed for the easy division of property upon death of the farmers.