“A garden in Giverny that used to be owned by Claude Monet, where he did many of his paintings. The famous Monet bridge (as used in his paintings). Not sure if it is a new bridge or the original one.” Photo by Elliott Brown, 2009, licensed under Creative Commons

Utopian text

Every garden is a utopian text, expressing the desire for a more perfect world as well as an implicit critique of the less-lovely world in which it is located.

– Naomi Jacobs, Consuming Beauty: The Urban Garden as Ambiguous Utopia

Claude Monet, no doubt speaking in French and so shared here translated prosaically into English, is quoted as having described his garden as “my most beautiful masterpiece” – perhaps this, if not accurate, is at least more poetic: “Mon plus beau chef-d’oeuvre, c’est mon jardin.”?

Which is quite saying something, though you don’t have to look far to find the convergence between his garden and the other works for which he is justifiably well known.

During the “Great War” (Monet would have been broken when we had to start numbering them) a numbed Monet retreated into his garden at Giverny. From Royal Academy curator Ann Dumas, setting the scene for a 2015 exhibition of what the RA called “garden painters”:

Monet’s monumental canvases of his water garden painted in the last decade of his life – the Grandes Décorations (1914–26) – are the ultimate expression of the symbiosis between his garden and his art. They would seem to offer a retreat into a world of tranquil beauty, an aesthetic immersion in the garden that obsessed him for the last 30 or so years of his life. Yet, for Monet these works carried another layer of meaning, beyond the garden. They were his very personal response to the mass tragedy of the First World War. “Yesterday I resumed work,” he wrote on 1 December 1914. “It’s the best way to avoid thinking of these sad times. All the same, I feel ashamed to think about my little researches into form and colour while so many people are suffering and dying for us.”

From the garden, Monet could hear the guns, the “less-lovely world” beyond his garden walls.

The Duranes ditch

The Duranes ditch in Albuquerque’s North Valley, March 2023, photo by John Fleck

Our Sunday bike ride (it’s book research! totally counts!) looped and wandered with a vague destination of the Duranes ditch in Albuquerque’s North Valley. It’s the setting for what I think will be a critical scene in the conclusion of the book Bob Berrens and I are writing. Here’s the key bit:

As a terrifying pandemic fog enveloped the world in the warming late spring of 2020, the Duranes Ditch in Albuquerque’s North Valley was transformed.

Treelined and cool, the Duranes has the quasi-geologic structure of a traditional New Mexico acequia, berms on either side created by centuries of spring cleanings to keep the slow, cool water flowing. Ditchbank berms have become walking paths through the neighborhoods on the Albuquerque metropolitan area’s valley floor, tree-lined and cool against the summer heat.

In the spring and summer of 2020, the Duranes became a pandemic lifeline, the normal trickle of ditch walkers turned into a flood.

When I read Dumas’s story of Monet in his garden painting with the sound of shells in the distance, I was struck by the parallels with the pandemic ditchbanks of the valley – the desire for a more perfect world, existing precisely because of the tension with the staggeringly “less-lovely” world beyond.

And gardens.

I’m writing on the edge of my comfort zone here with this garden stuff. There is a rich literary tradition around the idea, a line that starts with the Old Testament. (I realize it has issues, but the King James of my childhood will always be poetry to my atheist ears – it is at the heart of both my rebellion against organized religion and my learning to write.)

And the lord God planted a garden eastward in Eden; and there he put the man whom he had formed….

And the lord God took the man, and put him into the garden of Eden to dress it and to keep it.

But the story of Eden, crucially, only stands in contrast to that which lies outside of it, our “mortal coil”.

I am not a “rich literary tradition” kind of writer, more comfortable in my wonkish policy realm. But our story demands it, so I’m taking a dive into the ideas of gardens.

“gardens of the new West”

Testifying before the House Committee on Irrigation and Reclamation in December 1930 on S. 4123, “An act to provide for the aiding of farmers in any state by the making of loans to drainage districts, levee districts, levee and drainage districts, counties, boards of supervisors, and/or other political subdivisions and legal entities, and for other purposes,” Mr. J. Rupert Mason of San Francisco, Calif., sung the praises of reclamation and gardens:

these epoch -making achievements have gone steadily forward, under fair and foul economic conditions during periods of high mortality for railways, industries, banks, and commercial institutions, and to-day irrigated agriculture stands in the front ranks in annual earnings and total assets on the capital investment which changed the old deserts into gardens of the new West.

Mason (I have no idea who he is, I just ran across the garden reference while I was hunting through congressional testimony for some other stuff) is drawing a contrast here, between the “mortal coil” of the great depression and the Edenic “gardens of the new West”.

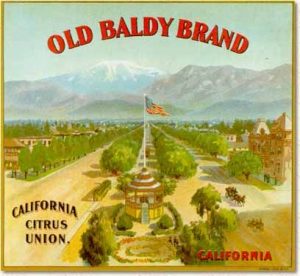

Old Baldy Brand oranges

Whoever he was, Mason is doing something crucial for the narrative Bob and I are crafting: His “gardens of the new West” stretch beyond the crop revenue-producing agricultural lands.

One writer, referring to the part irrigation and drainage have taken in building up a great western city and contrasting the irrigated areas with the unirrigated, says, when referring to that city:

“Its broad avenues are embowered in luxuriant foliage and the adjacent orange

groves and fine fruit gardens present a marked contrast to the vast barren unirrigated

regions thereabout not yet touched by the magic wand – water.”

I have no idea where Mason’s “one writer” is talking about, but I grew up there. The town of my birth, Upland, California, was richly green with the luxuriant foliage left behind when its fine citrus groves slowly handed the future off to suburbia.

This is the crucial point of the book. When we make irrigation canals and drainage ditches, we are not merely bringing the land into a crop export economy. We are building gardens in which to live.

Monet’s turnout

Look closely at Elliott Brown’s photo at the top of the post. Through the bridge (almost certainly rebuilt since Monet’s time) you can see the handle of the turnout used to control the flow of water into Monet’s lily ponds.

Gardens need tending.