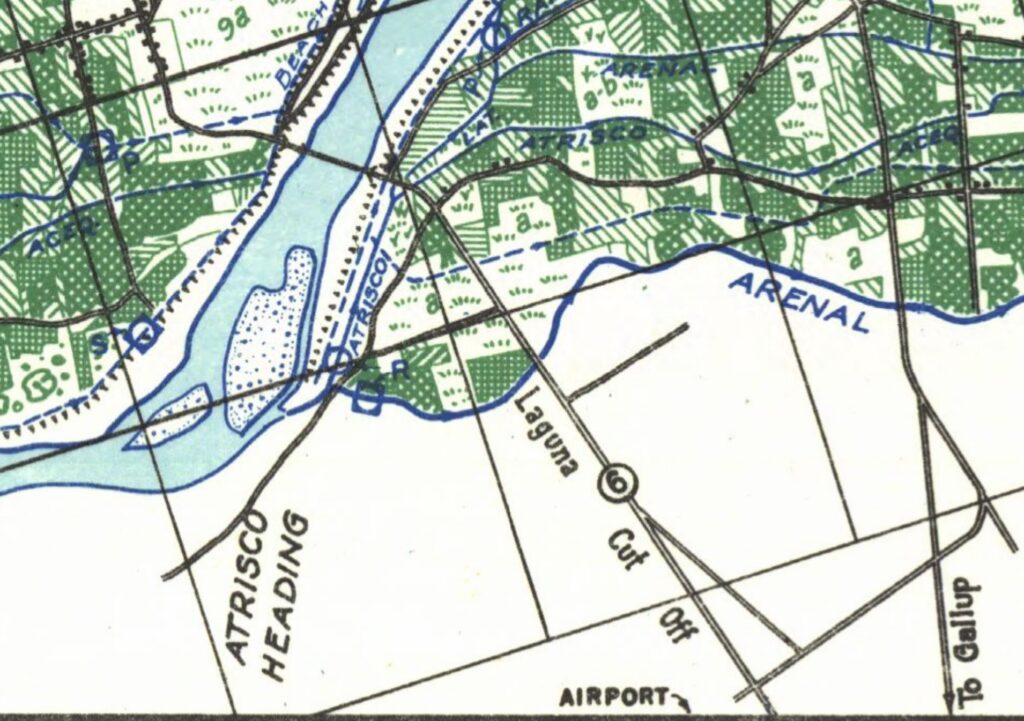

Atrisco, circa (I think?) 1936

It’s taking me a while to figure exactly what “the new book” is about.

In an early manifestation (I recall such things based on the names of computer file folders of my scribblings) it was called “the ghost of water”.

The idea was to find threads of the past in the stuff we built to manage our relationships with water, traces remaining of human-built water courses long gone, and of the things we did with the non-human built water courses.

Two stories, or maybe three.

River Westbourne

Westbourne River, in a pipe

A decade ago, when Lissa and I had gone to London for a couple of weeks on a lark, I visited the Sloane Square underground station to see the River Westbourne, carried over the tracks in a big steel pipe.

I’d stumbled in a London bookshop on a slim volume on the city’s lost rivers. Book in hand, Lissa and I wandered from our hotel down to the Thames to the Walbrook Wharf. It was the river that flowed through the old Roman London (the walled city, hence “wall brook”). Its outfall today is at Walbrook Wharf, where container ships fill daily with London’s garbage for the trip to Essex. Seems fitting.

Guerilla historian and urban explorer Steve Duncan wrote this bit:

[C]ities are organic growths that re-use and build on their past. Therefore almost nothing in an older city is going to be perfect, because the systems and infrastructure in use are so often leftover from an earlier period of growth. It’s imperfect, but nonetheless I love seeing the sort of cut-away view of both the history and the physical structure of a city that you get from seeing old underground systems in a modern city.

For “underground” here, substitute “water”. I realized on that London trip a decade ago that the ghosts of water were always there, and that they were a story worth trying to tell.

I also realized a guerilla historian would be a cool thing to be.

Upland

I grew up in a California community called Upland.

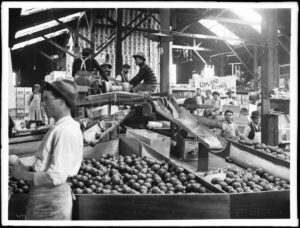

Packing citrus, Ontario California, circa 1905. Photo courtesy University of Southern California Libraries

It was, in the 1960s of my youth, on the fringe of the suburbs extending east from Los Angeles, part of the great citrus empire that grew in Southern California after the glorious invention of refrigerated rail shipment brought the exotic delicacy of navel oranges from California to the eastern market.

Upland was part of an irrigation colony developed by the Chaffey Brothers, who brought a convergence of hydraulic engineering and institutions. The engineering got water from the foothills onto the fertile alluvial fans of my childhood, but you needed institutions – the tools of collective action – to make the whole thing work.

The ghosts were there in my backyard, a little concrete irrigation turnout that once watered the citrus trees that had been carefully preserved as our suburban home was built atop the old farmland. It was long after, as I began learning and teaching about water management institutions, that I realized the ghosts of the institutions mattered ever bit as much as the physicality of the thing. For across the street from my childhood home was a tiny reservoir, and it still delivered water – not to groves now, but to homes – courtesy of the San Antonio Water Company, the ghost of the Chaffey brothers’ institutional innovations.

The Ghosts of Institutions

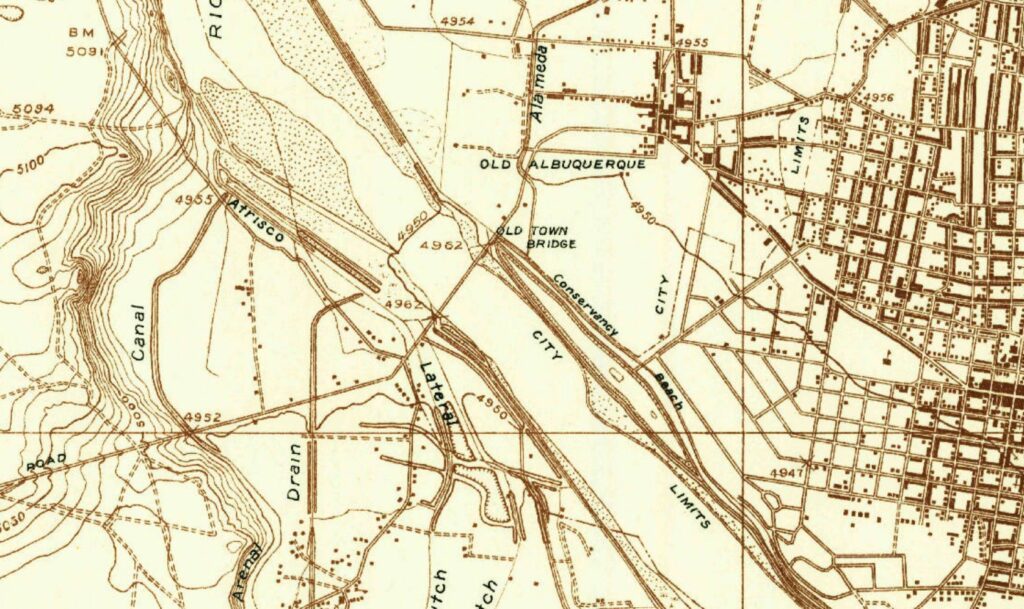

1934 USGS Topographical Map of Old Albuquerque, Atrisco, and the Rio Grand

The shift here – from the physical ghosts of water past to the more ephemeral ghosts of institutions – is the critical piece for understanding where the new book is headed.

Still feeling weak from my CRWUA Covid but desperate to get out and get some exercise, I threw the bike in the car this morning and drove down to the river. Or, more particularly, to Atrisco, next to the river.

It’s at the spot where Albuquerque’s Central Avenue Bridge – Route 66 – crosses the Rio Grande. But, more importantly for out story, it’s where three old ditches that once irrigated what we now call Albuquerque’s “South Valley” had their headings.

Was a time, in the 1700s, when this was the region’s largest population center – the Spanish villages of Atrisco, Pajarito, and Los Padillos. These communities had the best access to sheep and cattle grazing lands to the west. Villages with subsistence farming on the valley floor. Three ditches – Arenal, Atrisco, and Rancho de Atrisco – all had their headworks along a quarter mile stretch of the river bank here. The ditches, providing irrigation water for those subsistence farms, were at once physical and institutional plumbing, the collective action required to dig and maintain the system going on for centuries.

In the 1930s, the individual, community-based systems were taken over by a new collective, the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District, based on the realization that managing the relationship between the Rio Grande and a growing city required collective action at a larger scale – the individual ditch institutions were incapable of acting at the scale for providing flood control and drainage to the community, which were increasingly the most pressing tasks.

But here’s the interesting ghostly part.

Again and again looking the old maps, I find clusters of ditches with headings near the same spot on the river, each branching off to irrigate a separate down-valley village’s farms. The sophisticated engineers of the 1700s could see, as the river rose to spread across the valley floor during high spring runoff, where the high ground was. The Rio Grande provided a level. Above it was the place to build a village, or el camino, or the headworks of a ditch, which would then follow the contour of the land.

The chapter I’m working on is in terrible shape right now, which is always the case before they get good. But I notice myself writing, over and over again, about this “high ground” thing, ghosts on the landscape of a river we can no longer see and communities adapting their way of life around it.

The title of the post comes from the Herrera Ditch, which my maps show as an abandoned ditch running through what is now an Atrisco neighborhood, just north of El Super, as its name implies, a market – with a great taco bar. (And if you’ve read this far, Bob S, in season they do chile roasting in the parking lot.)

I couldn’t find a trace of the abandoned reach of the Herrera.

This is actionable information. Ghosts remaining are important, as are those obliterated by the erosion of time.

Ribbons Green

The book is Ribbons of Green, which Bob Berrens and I are writing for the University of New Mexico Press. It’ll be a while yet.

Your deep affection for these places comes through loud and clear. I also picked up what I’m calling Covid+ at CRWUA. I wonder how many people did.

Brian – Re my affection for the places – thanks for noticing! I am so attracted to writing about place, and I hope to place that at the heart of the new book. Your comment gives me hope that it’s working. Sorry about CRWUA+. 🙁

The collective MRGCD was largely formed due to the absence of proper drainage. The Rio was very aggradational at the time, in part due to natural processes and in part due to severe logging that was occurring to feed the railroad and other industrial development that was beginning for the first time in the late 1880s. The aggradation and lack of centralized drainage resulted in severe water logging of the middle valley. The MRGCD was formed to remedy this. The two headings at Atrisco and Bernardo were abandoned, at least in part due to the large amount of maintenance required due to sand deposition.