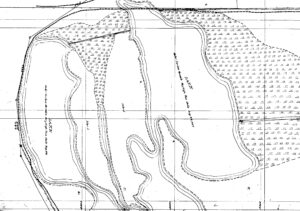

The Hubbell Oxbow, a “lake” in Albuquerque’s South Valley turned flood control channel (with bonus cottonwood grove)

The big farms we have left in Albuquerque’s South Valley are weird.

Riding the old Hubbell “Lake” and Anderson Farms – red is the Sunday bike ride

I spent a good fraction of my weekend staring at maps of them, or riding my bike around them, or both.

My co-author Bob Berrens and I have zeroed on in this area for a key part of the storytelling in our new book, Ribbons of Green. It has it all:

- the old Camino Real running up the river’s edge

- an enduring indigenous Pueblo to the south

- two enduring (?) Spanish-era villages

- 21st century farm land that is crucial to our narrative precisely because it is not enduring

It’s this last bullet that was the focus of my latest squiggly Sunday outing.

Gardens

The book will be published (once we write it!) as part of the University of New Mexico Press’s New Century Gardens and Landscapes of the Southwest series.

The notion of “gardens” came to us after the notion of the book, which is an effort to tell Albuquerque’s story in terms of our community’s relationship with its river. By our “relationship” with the river, we do not mean how we feel about the river today, how we interact with it, in its modern form. Rather, we’re trying to tell the story of how we came to build our city in the bed of the river itself. Because the Rio Grande of today, pinned between levees, bears little relationship to the river the Puebloans, the Spanish, and the early Americans confronted when they set about to build a city here.

Here’s a squib from the book’s opening chapter:

Through its history, the English language word “garden” has done yeoman’s work, traveling with us as we made a modern world. At its simplest, it is a noun describing a place out behind the house where we grow flowers, and vegetables, and perhaps a few fruit trees. At its most expansive, it is “a region of great fertility.” Kent was “the Garden of England”, “known for its abundance of fruit and crops”. The province of Touraine was “the Garden of France.” But it is the noun’s interplay with garden’s verb form that does the word’s linguistic heavy lifting – “to bring a landscape into a particular state” – to change our world.[ “garden, n.” OED Online. Oxford University Press, December 2021. Web. 27 February 2022; “garden, v.” OED Online. Oxford University Press, December 2021. Web. 27 February 2022.]

It is this notion of “bringing a landscape into a particular state” that has brought me, again and again, to the neighborhood around the Walmart at the corner of Coors and Rio Bravo in Albuquerque’s South Valley.

Hubbell Lake

Bob and I have been working with a bunch of old maps, trying to understand the evolution of that landscape as the community that was Albuquerque-in-becoming developed the institutions that eventually made it possible to put a Walmart in a spot that, as recently as the 1920s, had been labeled “lake” on the maps of the day.

The largest farms left in the Albuquerque reach of New Mexico’s Middle Rio Grande are here – much of the land in public ownership, leased to alfalfa farmers selling their crops to local equestrians, an effort by the community to preserve an agricultural heritage that looked nothing like this.

And not here. The agricultural heritage of this landscape is a recent creation, only made possible when the community added what looks kinda like Dutch technology – dykes to keep the river in its place, and drainage to lower the water table from the land beyond.

This was a flood path, a sweeping bend in a secondary river channel, inundated in high flows, that was used in the time before as pasture and a duck hunting club.

Thus does “lake” become farmland and a Walmart. It’s a very 20th century innovation. Before we did all this stuff, this stretch of the valley was salt grass marsh and “lake”.

This is the project of our book – to explain the processes of collective action that brought this particular landscape into this particular state – “gardening”.

A Lovely Grove of Cottonwoods

On our Sunday bike ride, my friend Scot and I rode into the Hubbell Oxbow from the west. The land is outside Albuquerque’s city limits, but is owned by the city’s Open Space program. It’s not really open to public access, but it’s easy to get in via the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District’s Gun Club Lateral, the irrigation canal built in the 1930s (? – further research needed, but we think this timing is correct ?) and/or the Albuquerque Metropolitan Arroyo Flood Control Authority’s Hubbell Channel, built in 1978. (I’m more confident about that date, which I got from the AMAFCA GIS database we’re using.)

Scot’s an incredibly important unindicted co-conspirator on the project, assisting in the crucial research task of aimlessly riding our bikes around the valley floor looking at stuff.

Our current work in the South Valley is thorough.

Looking at stuff is key.

The stuff we found Sunday, slipping into the Hubbell Oxbow from the back, was lovely. Wrapping around the back of the farm, protecting the farmland itself with a levee, is a flood control channel and basin that have, in fine AMAFCA tradition, become a greenspace. I was about to type “community greenspace”, but that doesn’t seem quite right if, by “community”, we mean a place where the locals walk their dogs and ride their horses and bikes. Despite the easy access, it doesn’t seem to get much of that sort of use. To quote the city, “The property does not offer formal access.” (emphasis added)

But if by “community” we are comfortable attaching what the economists might call an “existence value” – a thing that we value simply in the knowledge that it exists, rather than a “use value”, which we value via horse and bike and dog walk, then yes: “community greenspace”, I guess.

This spot is a classic type section of the “ribbons of green” of our book’s title.

I wish you had shown how the 1920 plane table map registers to the modern image. The orientation and scale are not obvious. Also I would love to know if building on these sediments created in any engineering challenges or resulted in any structural failures