For a brief moment, this was Albuquerque’s “Tobacco Farms”. Before that, a swamp.

Albuquerque’s nod to its agricultural past, like much of the style we have adopted for ourselves, is in significant measure artifice. This is not to say that it is not in some vague sense rooted in a truth, an actual past. But we engage in the 21st century in significant embellishment, a story we spin out on the land.

One of the last large farms in the urban part of this stretch of the Rio Grande, “greater Albuquerque”, is in what we call the “South Valley”. It’s ~350 acres of alfalfa, broken in two, separated by a Walmart and an uncrossably, dangerously busy highway. (This is your bike riding author’s humble assessment, having tried on more than one occasion to cross from one part of the farm to the other without aid of automobile. Do not try this without the aid of a skilled South Valley guide.)

Some of the land is in private hands, a proto-development with alfalfa parked on the land (the owner gets a good tax break) until the market hits that point of equilibrium where building stuff on it makes sense. The rest is in public ownership, an enthusiastic but perhaps historically misguided civic sense of self, directed toward preservation of an agrarian past that, while real, looked very different than the picture above.

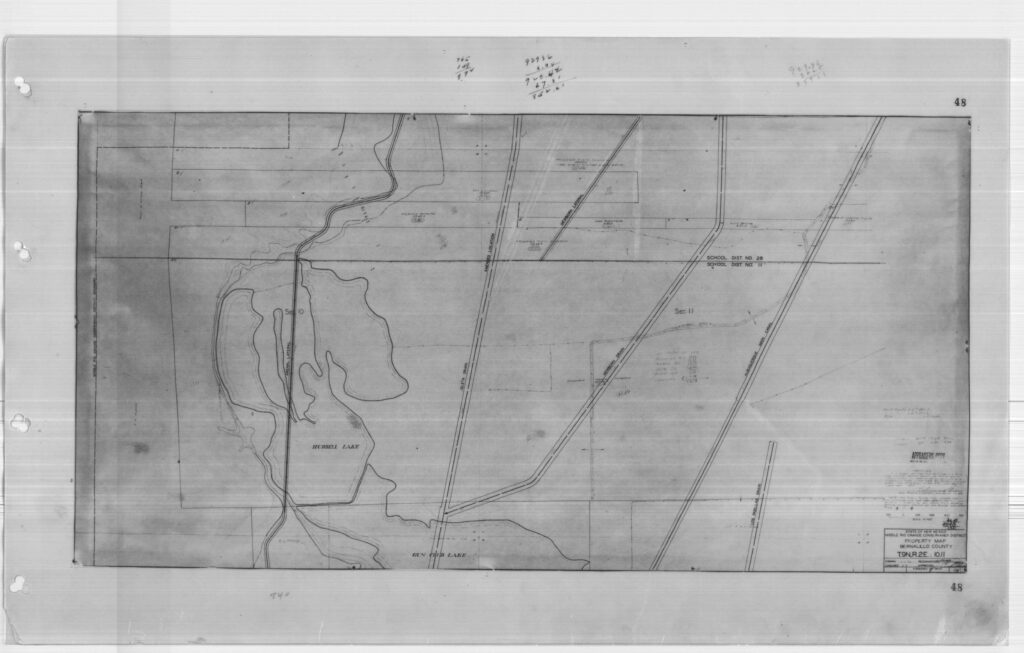

The early 20th century property records bear an odd name: “Consumers Tobacco Co.” The old maps also show something very different than what we see today – swamps, and lakes. “Water surface variable, very high this date. Aug. 29, 1927”, one of the old maps reads.

The tobacco name lingers in “Tobacco Farms LLC”, the legal owner of a good fraction of the land.

The swamps and lakes are long gone, drained away by deep ditches dug nearly a century ago to turn swamp into a tobacco-farming empire.

Like so many of this valley’s attempts at landing on a successful commercial crop – large scale wheat farming, tomatoes, pinto beans, orchards, sugar beets – this did not go well.

Tobacco Farms

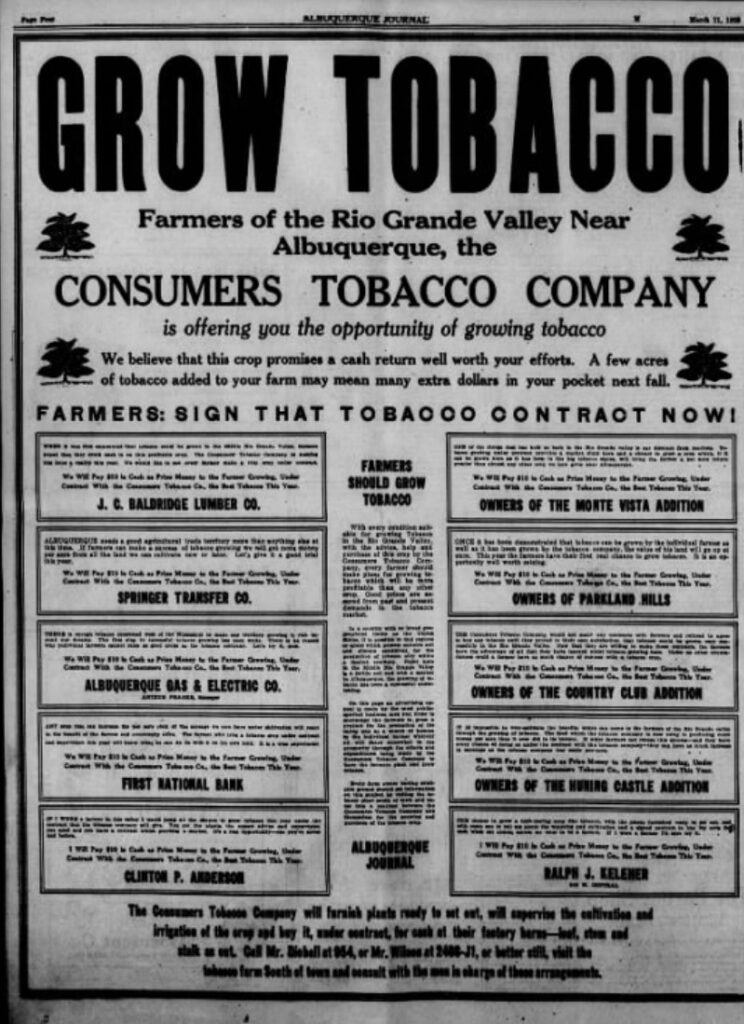

Albuquerque Journal, March 11, 1928

The advertisement in the March 11, 1928 Albuquerque Journal seems profoundly out of place.

The signatories, the members of a consortium that in in the 1920s had formed the Consumers Tobacco Company, were an odd assortment for an agricultural enterprise – an insurance agency owner, a lawyer, four developers of subdivisions in the burgeoning area around downtown Albuquerque, a warehousing and shipping firm, the Albuquerque Gas and Electric Co., and the First National Bank.

The ad was one of many run by this group of civic boosters. Why were they – no farmers themselves – so enamored with a crop that seemed so out of place in the arid West? The answer can be found in the advertisement’s words attributed to the First National Bank: “Any crop that can increase the per acre yield of the acreage we have under cultivation will react to the benefit of the farmer and the community alike.”

That “benefit … to the community” was the key. That’s why a bunch of housing developers thought tobacco was the answer to Albuquerque’s future.

These people were pursuing Albuquerque’s destiny as a great city. The citizens of this growing metropolis needed jobs, and a contemporary understanding of the economic structure of the day – remember this was the 1920s – saw those jobs in a “Von Thunen Ring” of farming around the city. Never mind that by the 1920s Albuquerque’s food was arriving by rail, and local agriculture even then could not compete. The economic structure of the nation was shifting beneath their feet, and it was hard for the Kelehers and Clinton P. Andersons of the day to see beyond the confines of their paradigm.

Draining the swamps

To build that city, these civic entrepreneurs needed to drain the swamps that made up the bulk of the land on the valley floor.

“It’s pretty hard to develop economically in a marsh,” New Mexico State Engineer Steve Reynolds said years later.

This is the heart of the book Bob Berrens and I are writing (credit here to Bob for the work we’ve been doing on the Tobacco Farms story – Bob’s the smart guy, I’m the literary muscle, a bouncer standing at the door of the Ribbons of Green nightclub deciding which stories to let in). To understand Albuquerque’s pivot in the 1920s from swampy valley to booming city, Bob and I have been spending an inordinate amount of time staring at three sets of old maps. (Huge thanks to the staff at the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District for helping us with the complete map sets.)

If you look at the Tobacco Farms maps, you see swamps, and lakes, and a bold straight line drawn through the middle of the page – “Isleta Interior Drain”. It’s deceptively simple – dig a big ditch through the marshland to lower the water table, and voila – swamp becomes farmable land!

But the deception is perhaps in the goal? If you compare the list of names on the newspaper ad above, the founders of Consumers Tobacco Company, you see not farmers but developers. You also see, crucially, a who’s who of the backers of the creation of the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District.

And if you head east across the 1927 maps, you see something striking. Before the drains were even built, while they were still dreams in the eyes of the Kelehers and Clinton P. Andersons, a carefully platted tract of homes: “Tobacco Farm Subdivision”. Immediately to the east is another ditch – “Atrisco Riverside Drain”.

We see this up and down the valley – even as the rhetoric (and some of our modern mythology?) suggests an attempt salvage and boost agriculture on the valley floor, a network of drains, and subdivision after subdivision being platted on the resulting newly reclaimed swampland.

In the 1929 census, tobacco peaked at 15 acres in Bernalillo County, never to be seen again.

Tobacco Farm Subdivision remains.

The first environmental science project I did was a historical analysis of urban pollution recorded in sediments of the Ala Wai Canal in Honolulu. The canal was dredged to drain Waikiki, which had been much larger than today and a rich agricultural swampland**. Now, of course, it is packed cheek to jowl with hotels and tourist traps.

http://waikiki.com/insiders_guide/history_of_waikiki.html

The canal itself was largely anoxic in the area I worked in, so it had a very good stratigraphic sequence of everything that poured out of the Manoa/Palolo/Makiki drainages for the time since the canal was built in the 1920’s. You could see the rise in urbanization in the lead and other heavy and industrial metals that were swept out of the watershed. Was an interesting study and we used it to spin up the NSF Young Scholars Program at the U of Hawaii.

There is a bike part of the story. In the work fellow scientist Eric DeCarlo and I did, we met this guy John Goody, who was VP for an environmental firm, Belt Collins Hawaii. In the inevitable drinking of beer between colleagues, I got John into bicycling, and he ended up as a very enthusiastic cyclist as well as board member of the Hawaii Bicycling League.

What a fascinating story of historical patterns and societal drivers of landscape change (real and dreamed of) in the Middle Valley. It’s a great teaser for your prospective book, makes me want to read it right now!

I agree with Craig Allen: This is a fascinating story and makes me want to read and learn more. I got curious about why the MRG would be inundated and covered with swamps and found this on Wikipedia: “After [irrigation peaked in the 1890s] there was a steady decline in irrigation due to “droughts, sedimentation, aggradation of the main channel, salinization, seepage and waterlogging”. Part of the problem was caused by increased use of the river for irrigation in the San Luis Valley upstream in Colorado. Development and deforestation there caused silt to be washed into the river. Where the river widens and slows in the middle Rio Grande valley around Albuquerque the silt was deposited, raising the riverbed and the water table and causing waterlogging in the farmlands that border the river. By the time the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District was founded in 1923, more than 60,000 acres (24,000 ha) of farmland had become swamps or alkalia and salt grass fields. Floods were another hazard, often destroying whole villages.” What did the Middle Rio Grande floodplain look like – and how much land was irrigated – before this major “siltation event”?

Patrick – The questions you’re asking are central to the book, and Bob and I are pursuing the answers. The story you see in Wikipedia is a well-understood narrative, which aligns with the MRGCD’s version of its own history – its founding narrative. There is good reason, though, to think that while the siltation and rising water table were a real problem, the valley floor has always been dominated by swampy land, and that the historically irrigated acreage was never as large as that founding narrative would like to claim.

Pingback: The peculiar economics of the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District - jfleck at inkstain