By Eric Kuhn

For years, the Colorado River management community has ignored, or at the very least sidestepped, a problem that has effectively sent more Upper Basin water downstream to help fill Lake Mead. But with the reservoir system operating on razor-thin margins, this “bonus water” – seeping through the sandstone cliffs of Glen Canyon, rather than being released through Glen Canyon Dam’s penstocks – could become a significant issue soon.

That leakage adds up. 150,00 acre feet per year is 1.5 million acre feet every ten years – enough, had it not been sent downstream to Lake Mead, to have pushed the Lower Colorado River Basin into shortage four or five years ago.

On April 8th, Assistant Secretary Trujillo formally informed the Colorado River Basin States that the Bureau of Reclamation would like to make a mid-year correction to the operation of Glen Canyon Dam, reducing this year’s annual release from 7.48 maf to 7.0 maf. This action coupled with additional releases from upstream reservoirs is deemed necessary to help prevent Lake Powell from falling below the minimum power elevation. Clearly, if aridification continues, more proactive measures will be needed including revisiting the issue of how annual releases are managed considering what basin insiders refer to as the Lower Basin “bonus water”.

The 2007 Interim Guidelines include storage tiers that are used to set and adjust the annual releases from Glen Canyon Dam. These annual releases, however, are not the same as the flows at Lee Ferry, the compact point. There are two sources of water between the dam and Lee Ferry; the Paria River which has an average annual flow of 20,000 af/year and groundwater inflows below the dam which, since 2010, have averaged about 150,000 af/year. The negotiators of the 2007 Interim Guidelines considered the Paria (this is the reason the flow levels are 7.48 and 8.23, not 7.5 and 8.25), but did not consider the groundwater inflows for the simple reasons that the data were not then available and there had always been an assumption beginning with the promulgation of the first Long-Range Operating Criteria in 1970 that releases from the dam and the flow at the Lees Ferry gage would be the same. Former UCRC Executive Director Don Ostler coined the term Lower Basin “bonus water” to label these groundwater flows.

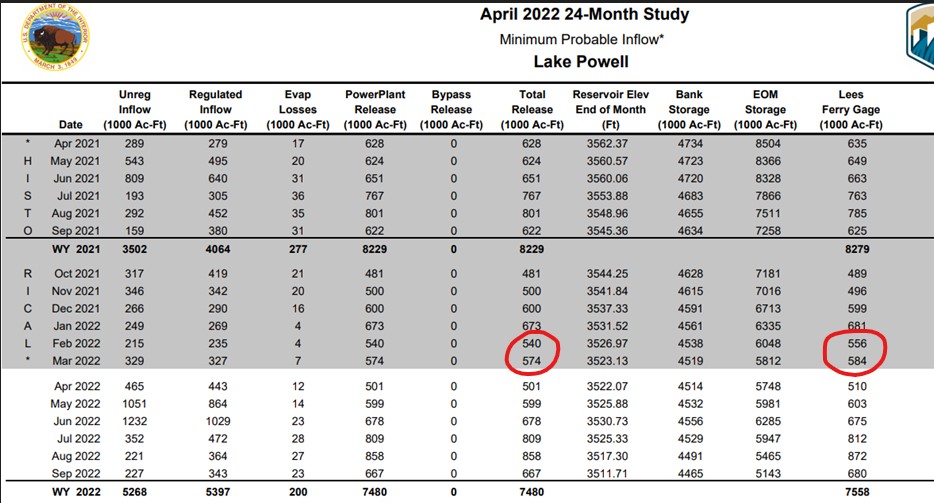

The 24-month studies show both the monthly releases from Glen Canyon Dam and the monthly flow at the Lees Ferry gage (about 1.5 miles upstream of the Lee Ferry compact point). Shown below is an excerpt from the April 2022 24-month study:

“Bonus Water” flowing past Lee’s Ferry

I’ve highlighted the total releases from Glen Canyon and the Lees Ferry gage flows for February and March 2022. In February the flow at the gage was 16 kaf greater than the release from the dam. In March the difference was 10 kaf. If one checks the 24-month studies back to 2010, the average annual difference between the gage and the dam release is nearly 151 kaf.

The annual amounts of bonus water vary considerably from month to month and year to year. There is a weak correlation between the annual regulated inflow to Lake Powell and the annual amount of the bonus flows and the monthly flows show a seasonal pattern, monthly bonus flows are the highest in mid-summer and lowest in late fall.[1] In 2019, the last wet year, the bonus flow was 270 kaf. For the 2021 drought year it was only 50 kaf. While 150 kaf/year may only be a small fraction (1.8%) of the normal annual release of 8.23 maf/year, over ten years it’s a big deal, 1.5 maf is over three times the 480 kaf reduction ordered by Assistant Secretary Trujillo. Had this 1.5 maf stayed in Lake Powell, its storage elevation today might be 20-25’ higher.[2] Further had it not been delivered to Lake Mead, a Tier I shortage may have been necessary 4-5 years ago forcing the Lower Basin to further ramp up their conservation efforts much earlier.

After the 2012/13 two-year drought, Ostler raised the issue of the groundwater bonus flows with technical representatives from the USGS, Reclamation, and the other states. The USGS looked at the gage issues and concluded that while not perfect, the accuracy of the Lees Ferry River gage and the ultrasonic flow meters used at the dam are state of the art. The bonus flows are not an artifact of gaging error. Further, a visual inspection of the river below the dam showed numerous springs and weeps. Despite these finding, there was little interest by the Lower Basin States or Reclamation representatives for using the Lees Ferry gage to manage monthly releases from Glen Canyon Dam.

The movement of reservoir water into bank storage, through the sandstone then back into the river below the dam is obviously a very complicated hydrogeology problem. Factors include the hydraulic conductivity and fracturing of the rock surrounding the dam and reservoir (mainly Navajo Sandstone), the storage level in the reservoir, whether the reservoir is filling or draining, and others such as local precipitation. We may not understand the fine details of how the groundwater gets to the river below the dam or how much of it originated from the reservoir. But what we know with certainty is that the water is in the river at the Lees Ferry gage – the Compact measurement point – and it is flowing downstream to the Lower Basin.

While the easiest path forward may simply be to wait and address this matter as a part of the renegotiations of the 2007 Interim Guidelines, why wait four years (or more if the current package of Interim Guidelines and DCPs is temporarily extended)? The Secretary has the authority to operate Glen Canyon Dam to meet an annual target flow at the downstream Lees Ferry gage. Unless we get an unusual series of wet years, refilling Lake Powell and the upstream CRSP reservoirs is going to be a struggle. Using this approach could keep an extra 600 kaf in Lake Powell over the next four years. It’s more water than what might be squeezed out of Blue Mesa and Navajo Reservoirs under drought operations.

It won’t solve the basin’s basic math problem. Only a reduction in total demand to match the available supply will do that. But it will better balance the burden on each basin.

[1] Based on the 12-year period of 2010-2021, average monthly bonus flows are the highest in August at 23.8 kaf and lowest in November at 4.9 kaf. The correlation between annual regulated inflows and annual bonus flows (WY) has an R squared of .59 which is significant at the P<.05 level.

[2] This is actually a much more complicated question. Under the 2007 IG tier structure, as my colleague Ben Harding has concluded, Lake Powell storage has “memory,” Changes in storage in one year carry forward and impact future years. For example, in both 2020 and 2021 Lake Powell was in the Upper Elevation Balancing tier. The releases were 8.23 maf, but had there been more water in Powell, they could have been as high as 9.0 maf depending on the storage level in Lake Mead.

I’m not a chemist but doesn’t water have “finger prints”? I’ve seen studies of rivers where downstream groundwater inflows have been identified for the source. They found the difference between run-off and groundwater from percolation at higher elevations in prior years.

It is good to see that the federal government is being proactive and acting responsibly. Will the states and the other organizations act forthrightly?

“why wait four years (or more if the current package of Interim Guidelines and DCPs is temporarily extended)?”

Absolutely agree. Transition should have begun already. Negotiations should have happened before we reached this point. The compact needs to be rewritten. Yes, I know in the current political and economic climate that is almost impossible, but there seems little sense of urgency apart from those staring at it in the face.

All dams allow for a certain amount of seepage. Glen Canyon Dam’s seepage rates are actually quite low and mostly due to the sandstone canyons that the dam is built into. Accounting for this seepage (I calculate an average of 144 kaf/year since 2010) in annual release volumes would temporarily improve pool elevations in Lake Powell. It should be noted, however, that the Interim Guidelines that Mr. Kuhn mentions also provide for balancing the contents of the two reservoirs (Powell and Mead) and any water saved at Powell would eventually be released to achieve balancing. We’re simply taking more from our water storage projects than nature is providing and this situation cannot continue for much longer.