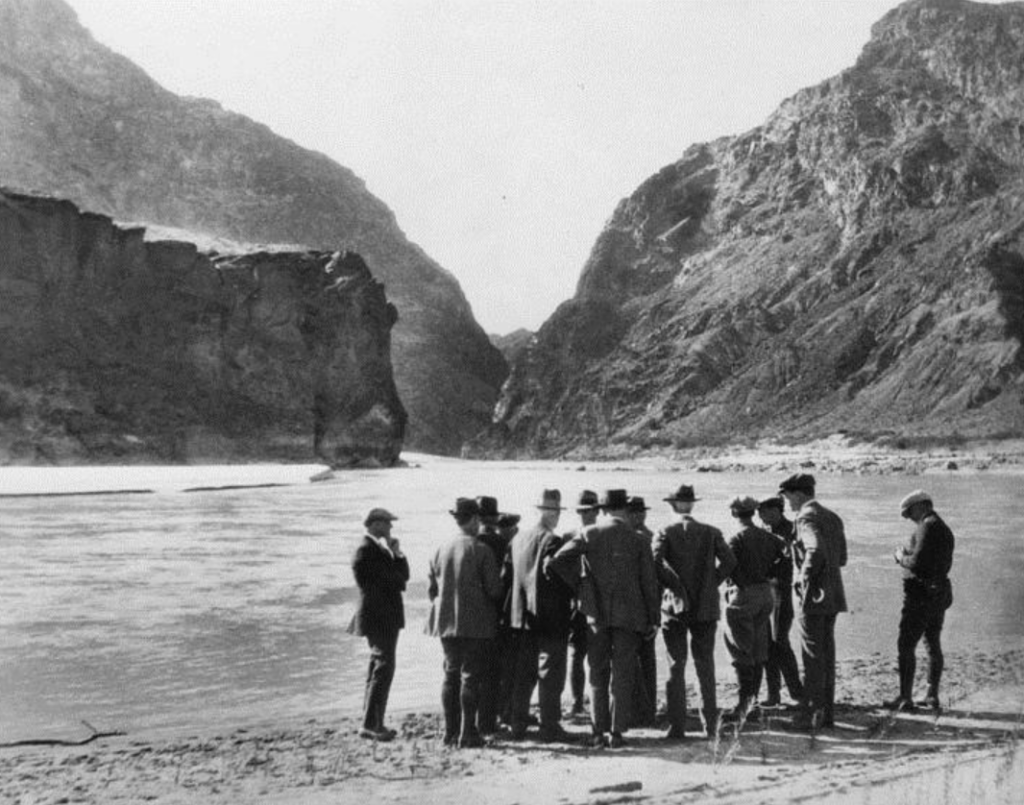

The Colorado River before Hoover Dam

By Eric Kuhn and John Fleck

On Saturday, April 1st, 1922, at 9:00 AM in Denver’s iconic Brown Palace Hotel, Chairman Herbert Hoover opened the 9th meeting of the Colorado River Commission. The official meeting lasted only 30 minutes. The commission took only one action of consequence. It asked its members to submit to Executive Secretary Clarence Stetson “suggested forms of compact for the disposition and apportionment of the waters of the Colorado River and its tributaries.” The commission would then consider these draft compacts at future meetings.

At 9:30 AM, the meeting ended, and the commissioners headed to the day’s main event, a public hearing at the Colorado State Capitol. The Denver hearing was the next to the last of a long series of public hearings and inspection tours that had begun back on March 15th in Phoenix. After Phoenix, the Commission visited the Boulder Canyon project site near Las Vegas and agricultural development in the Imperial Valley. It held three hearings in Los Angeles on March 21st and 22nd, then headed to the upper river where it held hearings in Salt Lake City and Grand Junction and inspected the federal Grand Valley Project.

Governors Join the Ruckus

The April 1 hearing was a big deal. Four of the basin state governors would join them; three from the upper river – Charles Maybe from Utah, Merritt Mecham from New Mexico, and Oliver Shoup from Colorado – and one from the lower river, Nevada’s Emmet Doyle.

In proposing the tour and public hearings, Hoover hoped to build both knowledge and social capital. While each of the commissioners was an expert in the water needs of their own states, there had never before been an effort to bring people together to think at the basin scale. Hoover wanted the commission to see and better understand the water issues facing the basin. He also hoped that during the two weeks the commission and their advisors were together they could get to know one another and engage in the candid discussions that could break the current impasse. In particular, he wanted to soften up Colorado’s Delph Carpenter, to get him to back off of his insistence that water projects on the lower river never interfere with development on the upper river. Hoover had asked New Mexico’s Steven Davis, a state supreme court justice, for help.

The tour was a big success. After visiting Boulder Canyon, the commission went south to the Imperial Valley. What they saw clearly impressed them. The Imperial Valley, which before irrigation promoter Charles Rockwood renamed it for marketing purposes was referred to as the Colorado Desert, is a vast expanse of potentially irrigable land, much of it at an elevation below the Colorado River channel just to the east of the valley. While some maps do not include the Imperial Valley as a part of the Colorado River Basin, those familiar with the geology of the basin consider that silly. Like the Grand Canyon, the Imperial Valley owes its existence to the river. The valley lies at the very northern end of the Salton Trough, a geologic feature called a “rift” created by plate tectonics extending from the tip of Baja California to Palm Springs. Over the eons, as the rift was subsiding the valley floor, the Colorado River was filling it in with sediment. The valley is a part of the river’s delta.

The Foundations, and Challenges, of Imperial Valley Farming

Rockwood’s California Development Company first delivered water from the river via a route through Mexico to the valley in June 1901. In 1911 the Imperial Irrigation District (IID) was formed to buy the irrigation works from the Union Pacific Railroad which had taken over Rockwood’s bankrupt company and saved the valley from the floods of 1905-07 when the entire river diverted itself through the newly constructed canal into the Salton Sink – as it had countless times in the past. In 1922 when the commission arrived, there were over 20,000 settlers farming about 300,000 acres of land. The IID needed help from the Reclamation Service in two major ways; a supply canal that avoided Mexico, an “All-American Canal”, and an upstream reservoir to help control the floods that were still threatening the valley. The recently released Fall-Davis Report made a strong case for both.

On to Los Angeles

From the Imperial Valley the commission travelled to Los Angeles where it held three public hearings. The Los Angeles of 1922 was a rapidly growing city of over 600,000 in a county with a population of over a million. It had already exhausted its local water supply and was importing water via a 220-mile aqueduct from the east slopes of the Sierra Nevada. While local community leaders may have been coy about plans to import water from the river, they made it clear that they wanted and needed the hydroelectric power the Boulder Canyon Project would produce. In Los Angles, Arthur Powell Davis first suggested that the Commission abandon the idea of apportioning water among the states. Davis suggested instead a split between an upper and lower basin. Davis’s proposal would allow unrestricted development in the Upper Basin for 50 years. Projects built during this 50-year window would be senior to all Lower basin uses. After the 50-year window, new Upper Basin projects would be subject to the priorities of existing Lower Basin projects.

Carpenter and the Sticking Points

The combination of the tour and Davis’ proposal made an impression on Carpenter, but not the one Hoover and Davis were hoping for. Instead, what Carpenter saw in California caused him, and Utah’s R. E. Caldwell, to double down on their demands that any compact be based on the principle of non-interference by Lower Basin projects on the Upper Basin, subject only to a possible limit on exports out of the basin. The issue of trans-basin diversions had been a hot topic during many of the public hearings. While perhaps open to a limit, all four of the commissioners from the upper river, as well California’s McClure wanted to keep the option open for their states.

In a choreographed performance at the Colorado statehouse, New Mexico Governor Merritt Mechem told the Commission that New Mexico could not accept a limited period (50 years) for development, unless the limit was so far in the future that it was no limit at all. For all practical purposes, most of the Arthur Powell Davis Los Angeles proposal was now dead.

After the Denver hearing, the Commission had one last public hearing scheduled for Cheyenne the next day. After that, it might be a while before the Commission could meet again. Steven Davis let Hoover know that any efforts to soften Carpenter might now be in hands of the United States Supreme Court. What it decided in the pending Wyoming v. Colorado case over Colorado’s tiny Laramie River would be big news for the mighty Colorado – stay tuned.

the point about the salton sink being a part of the Colorado River Delta is something that should always be in mind when considering the current situation.

in thinking more i was wondering what the value of the entire Salton Sea area would be if it was mostly drained (pump the salt water back to the ocean). so instead of worrying about desalinisation it would just instead be a matter of a big enough pipeline and enough pumps and the energy to run them for long enough. once the lake was pumped then any new inflows would be mostly fresh water so the salinity would decrease as the salts were leached from the surround built up accumulations as the rains and new ground water seeps were pumped out. you still lose a large lake, but you gain valuable agricultural land. not sure how this works out financially, but may be much easier to accomplish than another plan to import sea water to flood it again.

existing wetlands and fresh water sources could be maintained as best they can find the fresh water to do it. blended salty areas could also be maintained downhill as the salts leach and flow.

As Charles P. Pierce exclaims weekly in his Esquire column, “History is so cool!”

Terrific read. What Delph Carpenter saw in California spooked him for sure. Colorado state water law, was very clear on “prior appropriation “. These very laws were working against Colorado in the 1922 Colorado. vs. Wyoming Supreme Court case

After seeing the Imperial Valley, Delph Carpenter knew he had a one time chance to re-do the water appropriations on the Colorado River, to get back water rights that would, under the existing law, be already vested with the Imperial Irrigation District.

Since the Los Angeles aqueduct began delivering seemingly unlimited water from the Owens Valley to Los Angeles in 1913, they were not as interested in 1922 in getting additional water from the Colorado River. Electricity would have been their bigger need. That led Los Angeles to not supporting the Imperial Valley farmers, the IID, and their water rights. This created a rift of it’s own, between the LA Dept of Water and Power and the IID. A rift that exists today between the re-named Metropolitan Water District, the IID and the San Diego Water District. Los Angeles was happy to receive water rights it did not have before 1922, and that created a strain on their relationship with downstream water rights holders.

So before the Supreme Court case was even decided, the IID was on it’s ways to lose it’s water rights, and the City of Los Angels was gaining new water rights. More water for LA, and fewer water rights to farmers, was the LA playbook in that era. William Mulholland of LA was simply a better than the IID when it came to getting water rights.

The Internal fight over water rights in California is one of the things that allowed for the great re-assignment in the 1922 water compact without much push back from California.

The SCOTUS decision on a small northern Colorado river then sealed the fate for California and the lower basin states.