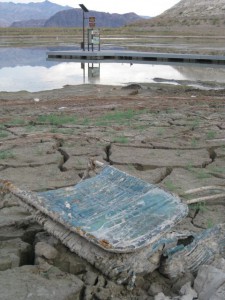

Boulder Harbor, Lake Mead, Oct. 18, 2010

I’m choosing my words carefully here. The “likely” in this blog’s post’s title means “based on my analysis of the Bureau of Reclamation’s current ‘most probable forecast’ Colorado River water supply model runs.”

The Bureau’s current “most probable” modeling suggests that in both 2022 and 2023, the annual release from Lake Powell will only be 7.48 million acre feet. This is based on a provision in the river’s operating rules that, under certain low storage level conditions, the Upper Basin gets to hang onto water in Powell.

The last time and only time we had a 7.48 release, in 2014, Mead dropped 25 feet in a single year. We’ve never had two consecutive 7.48 releases.

The headline in yesterday’s release of the Bureau of Reclamation’s “24-month study” (pdf here) is that Lake Mead will drop below elevation 1,075 at the start of 2022 (triggering a “Tier 1” shortage) and could drop below 1,050 by the start of 2023 (that’s the trigger for “Tier 2”).

Tier 1 next year, which primarily hits Arizona with some deep forced reductions, was no surprise. That’s been obvious for a while, and Arizona’s water leadership has been softening folks up for months. The increasing risk of Tier 2 in 2023, which would mean deeper cuts in Arizona, is sorta new, but it’s been foreseeable.

The real “holy shit” for me in yesterday’s release was the trail of breadcrumbs in the Bureau’s data, pointed out by my co-author Eric Kuhn, leading to a “most probable” Lake Mead drop to elevation 1,035 by the end of September 2023.

To be clear, the Bureau isn’t saying this yet. The latest 24-month study stops at the end of March 2023. But internally, the Bureau runs the model out farther in order to determine, among other things, how much water is likely to be released from Powell in 2023. And the published numbers clearly show – the Bureau’s “most likely” scenario would call for another 7.48 release.

From there, it’s just arithmetic. Based on my analysis of the publicly available numbers, the “most likely” scenario puts Mead at elevation ~1035 at the end of September 2023. This is my math, but my understanding is that it’s consistent with what the Bureau’s internal calculations show.

In my linguistic equivalence here between “likely” and “most probable forecast”, remember that I’m talking about the midpoint in a range of possible outcomes. A run of wet weather could make things substantially better.

But a run of dry weather could make them worse.

Oof, that’s scary on a bunch of levels. Thank goodness for giant concrete straws (though obviously not a solution to climate change)…

Nice analysis.

So I wonder at what point California starts getting cuts? They are by far the largest user. Doesn’t sound good for Las Vegas and Phoenix in the near future. With home values skyrocketing I wonder if it’s time to sell my Boulder City house. Man, I really don’t want to do that:(

Priority matters

Pingback: The April 2021 24-Month Study was a Shocker, but is it too Optimistic? – jfleck at inkstain

Pingback: #LakeMead likely to drop below elevation 1,040 by late 2023 — John Fleck #ColoradoRiver #COriver #aridification | Coyote Gulch

Pingback: When Predicting Less Leaves Room for More | Hydropower Reform Coalition