A bad start to 2021 on the Rio Grande

With another abysmal runoff forecast on the Rio Grande, New Mexico is entering a fascinating experiment, playing out in real time, in climate change adaptation.

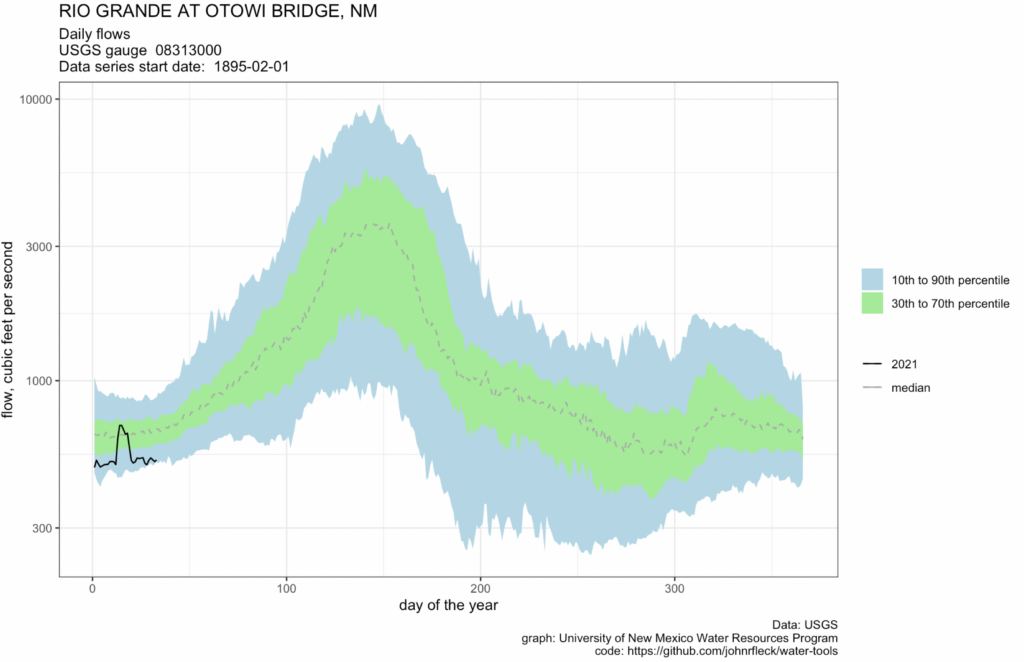

The latest model runoff forecast, circulated this morning by the folks at NRCS, is for flow of just 59 percent of average where the Rio Grande enters central New Mexico at a place called Otowi. That’s a midpoint forecast, with a big uncertainty range with a couple of months of snow season to go. But even the best case scenario at this point in the model is for below-average flow.

The worst case scenario is awful.

As my UNM colleague Dave Gutzler points out, there’s some really important recognition of the impacts of climate change embedded in these numbers. The snowpack isn’t actually all that bad. But (thanks to many scientists working on this question, but especially Dr. Gutzler and his collaborators here on the Rio Grande) we now understand that we should expect, for a given amount of snow, less water actually ending up in the rivers.

It’s warmer. Plants take up more water, and more evaporates.

What we also see is a sort of policy window opening up. In John Kingdon’s classic work on policy formation (see the indispensable Paul Cairney on this) the political/policy system, with limited capacity to wrestle with all the things before it, ignores lots of stuff until it doesn’t. Attention lurches from thing to thing, and when it lurches in your direction, you’d best be ready. But, importantly, you’ll be much more successful in contributing in that moment if the people doing the lurching already know you’re there. (Dr. Gutzler is a great example of this. He’s been soldiering along for years making himself available to explain this stuff, and doing the research to advance our understanding. Much of my own understanding of climate change came from many hours, during my time as a journalist, sitting in his office in what amounted to a bunch of on-demand graduate seminars.)

On the Rio Grande, one of those lurches is happening, now, in real time.

Consider first the Elephant Butte Irrigation District, on the Rio Grande in southern New Mexico. Per Veronica Martinez in the Las Cruces Sun-News:

“Unless conditions improve in the late fall and winter, we can expect 2021 to be a critically low water supply year for the Rio Grande Project, perhaps the worst in the project history,” Phil King, the district’s water resource consultant, said.

Meanwhile upstream in the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District, the stretch of river where I live, Theresa Davis reports:

The Office of the State Engineer recommends “that farmers along the Rio Chama and in the Middle Valley that don’t absolutely need to farm this year, do not farm,” according to a staff report that Interstate Stream Commission Director Rolf Schmidt-Petersen presented to the Commission earlier this month.

In my crazy new academic life, I’m watching this play out in real time with a couple of students, Tylee Griego and Talisa Barancik, who with funding from the South Central Climate Adaptation Science Center have been studying patterns of agricultural water use in the valley.

We’ve been exploring the distinction between commercial and non-commercial farming. There’s a gradation between the two, but the climate adaptation responses and opportunities seem very different. In places dominated by commercial agriculture, farmers seem farm more likely to drill groundwater wells to make up for surface water shortfalls. This is especially the case in the San Luis Valley, up in Colorado, and down in the Elephant Butte Irrigation District of southern New Mexico.

Here in what we call “the middle valley” – the stretch through central New Mexico that includes Albuquerque – the farming is far more likely to be non-commercial. It is people with a small operation and an off-farm job. Maybe it’s supplemental income, or maybe it’s just a “custom and culture” – farming as a thing integrated in a community’s life, rather than as a commercial economic activity. In “custom and culture” farming you see a lot less groundwater pumping.

These are the people more likely to be able to pull off Rolf Schmidt-Petersen’s “do not farm” recommendation.

I was Trustee of Natural Resources from 1996 to about 2004 as I recall. I commissioned a study of climate change from Rio Grande and Pecos River streamflow and climatic records about 2002 performed by the Canadian Environment Agency because they had developed what I thought was the most important analytical methods. It cost us about $15,000. One key prediction was peak runoff would be higher and the second was it would occur earlier in the season moving from mid-May to even April. From you graph it appears that that has occurred and they were right. That was about 20 years ago and no one was interested. If I can find it I will post it on my website http://www.waterbak.com I am quire sure I stored it on a CD Rom at the time.

Bill

Pingback: A bad year on the #RioGrande: #Climate adaptation in real time — John Fleck #ActOnClimate | Coyote Gulch