an old pickup in Valencia County, New Mexico, in the Rio Grande Valley south of Albuquerque, repurposed as a water pump

Somewhere around Mile 22 of a long Sunday bike ride, my friend Scot motioned to a dirt road off to the left, crossing the railroad tracks. “We’re turning there,” he said.

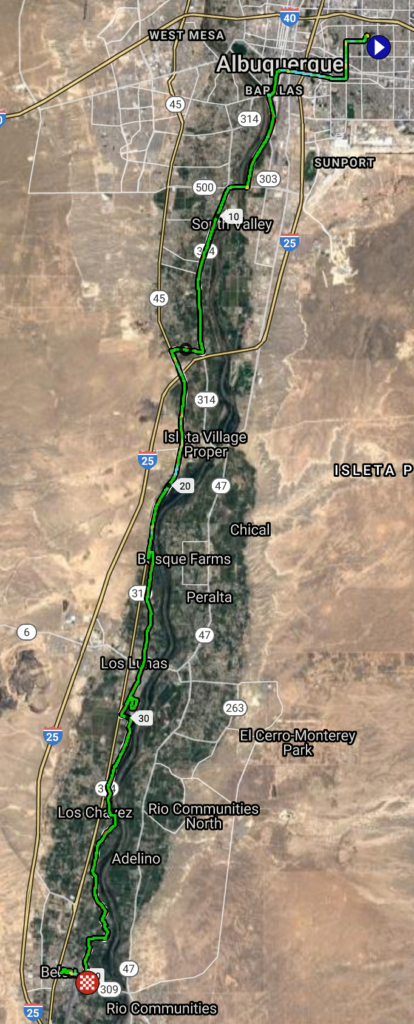

Albuquerque<->Belen via bicycle and Rail Runner

The ride down New Mexico state highway 314, through Albuquerque’s South Valley, across Isleta Pueblo and into Valencia County, is a lovely one, urban giving way to rural clutter, the farm fields growing larger the farther south you get. But it is a long way, and I am old and slow, so I haven’t done it in ages.

Scot’s suggestion that we ride our bikes to Belen and catch the 12:45 Rail Runner commuter train back to town, combined with the warmest Sunday of the year so far, made for a fine outing. Public transit as a bike ride extender!

Scot and I have ridden together for many years, and in so doing have developed a trust in one another’s “let’s try this” ideas. The Rail Runner suggestion was smart – Scot’s “let’s turn left across the railroad tracks” was genius.

Off the highway (lovely, but it’s a highway) we spent much of the next 20 miles riding Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District ditchbanks, dirt roads that flank the district’s canals.

The District is the irrigation, flood control, and drainage agency in our reach of the Rio Grande, stretching from Cochiti in the north to the Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge in the South. The District’s works support a narrow ribbon of green threaded through New Mexico’s largest population center. A central theme of the new book I’m starting to think about is the way water management institutions shape landscape – riding the MRGCD district’s is totally work related.

Highways are highways, you can see ’em anywhere. But the way the ditchbanks (and really the ditches themselves) stitch together irrigation communities is a different thing entirely. They feed water onto farm land – mostly growing alfalfa to feed livestock. They drain water away, or the valley floor would be a swamp in many places. And their roads are roads of a certain type – slow, and measured, and important.

They’ve been there nearly a century, and their predecessor infrastructures far longer, and I’ve been pondering what happens if we talk about them in the same breath as we talk about “nature”.

I’m not quite sure where we were when we came upon the slowly growing sound of sandhill cranes. Their honks are characteristic of the valley at this time of year, but this was a volume and intensity I rarely hear.

Sandhill cranes at a feed lot, Valencia County, New Mexico, February 2020

There were hundreds of them (500, a thousand? My bird counting skills were overwhelmed.), hanging with the cattle and in the adjacent waste pond. The picture above cannot do justice to the smell.

We build impressive wildlife and game refuges for the cranes. Also, feedlots. The boundaries we draw between “nature” and “not nature” yield usefully to inquiry.

Thanks to Scot’s wayfinding skills, we found our way back into Belen in time to grab some deli sandwiches at the Lowe’s Market on main street and catch the 12:45 Rail Runner home.

bikes on a train (technically from last week’s outing – this bike<->train thing is a thing – but the picture I took this week was jumbly)

Great pics. The pumping plant doesn’t represent the value of water, merely the value of the crop being watered, pasture. The cranes likely have better roosting along the river. They’re only cleaning up some waste grain, corn ?. Looking for a higher quality feed.