By Eric Kuhn

One of the central themes of last week’s Colorado River Water Users Association annual meeting was the was the role of the basin’s Native American Tribes in the many decisions that will guide and manage water use on the Colorado River over the next several decades (for example, the post-2026 Guidelines). CRWUA attendees heard a report on the Water and Tribes Initiative co-facilitated by Matt McKinney and Daryl Vigil.

Tribal Water Study

Tribal Water StudyWhile our book, Science Be Dammed, is primarily about the science (hydrology) of the river – What did we know, when did we know it, and how did we use it? – the research John Fleck and I did has given us some interesting insights on the how the basin states and federal agencies that dominated the development of the river viewed the water needs and rights of the Tribes.

Those familiar with the Law of the River know that the 1922 Colorado River Compact addressed the Indian questions with a single sentence. Article VII states “nothing in the compact shall be construed as affecting the obligations of the United States of America to Indian Tribes.” The provision was put in the compact at the insistence of Chairman Hoover. His original suggested language was “nothing in the compact shall be construed as affecting the rights of Indian tribes.” The minutes give scant reason for the language change that Hoover himself suggested. (Hundley, Water and the West, pages 211-12).

Based on the compact minutes and Hoover’s 1923 report to Congress, he considered the federal obligations to Indians as similar to future treaty obligations with Mexico. He considered both as core federal interests. Before the compact negotiations began, Mexico requested that it be formally represented on the commission. At the request of the State Department, Hoover responded that the compact was solely a domestic matter, but Mexico need not worry. Its rights could be determined by a treaty and “such treaty rights” he noted “will override interstate arrangements” (Hundley pages 175-6). During the negotiations Hoover cautions that without Article VII, Congress would include a reservation to protect tribal rights under treaties (Minutes of the 21st Meeting). In his analysis of the compact for Congress he notes that the provision disclaims “any intention of affecting the performance of any obligations owing by the United States to Indians” and “it is presumed the that the States have no power to disturb these relations” (The Colorado River Compact: Analysis by Herbert Hoover, January 30, 1923, answer to question #24).

In Water and the West, Hundley is critical of the commission, concluding that “no attempt was made to discover how many Indians were in the basin and what their water needs were. The Commission simply assumed that the water rights of Indians were ‘negligible'” (pages 211-12). Here, as with our message in Science Be Dammed, reality is more complicated. While there is no reason to disagree that the commission assumed the rights were negligible, the available technical reports suggest that, at least in the Lower Basin, the future needs of Indian tribes were well recognized and far from negligible. The 1922 Fall-Davis Report, the Reclamation Service report that shaped both the compact and the 1928 Boulder Canyon Project Act, identifies over 140,000 acres of tribal lands adjacent to the river below Hoover Dam that could be irrigated, including the Colorado River Indian Tribes and Ft. Mojave Projects, very similar to the Indian rights that were finally adjudicated in Arizona v. California.

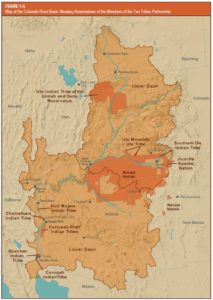

The conclusion of the recently completed Tribal Water Study that the water rights of the tribes exceed 2.9 million acre-feet might have surprised some, but it should not have. By 1944, when the Bureau of Reclamation’s comprehensive report on the development of the Colorado River was being finalized, the Bureau of Indian Affairs identified existing and future Indian projects that would divert (not consume) over three million acre-feet per year of water, including over 800,000 acre-feet in New Mexico (Proceedings of the Committee of 14/16, November 10-11, 1944). Because it acknowledged that Indian rights would be “superior” to non-Indian rights, the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact Commission gave New Mexico an 11.25% share of the Upper Basin’s apportionment (New Mexico provides <2% of the river’s yield) so that it would be large enough to cover the future needs of its Native and non-Native Americans.

For most attendees, the convention’s attention to the basin’s Tribal needs was a welcome and perhaps overdue step. The message I heard was that the basin’s Native American communities are fully engaged and expect that they will be given the opportunity to meaningfully participate in the decision-making processes that will shape the future of the Colorado River. In his remarks, Secretary Bernhardt appeared to offer them a seat at the table. Even so, history suggests, they will still have many challenges ahead of them.

If the Law of the River gave scant attention to the water rights of Native Americans, it appears it gave/gives no attention to federal reserved water rights, surface and sub-surface, of federal agencies, particularly those agencies not named Reclamation, such as the Department of Defense. For example, Yuma Proving Ground may or may not possess federal reserve water rights. Its water source is groundwater—”Our water supply for WCA and KFR water systems is derived from groundwater pumped from the Coarse

Gravel Aquifer, which lies in the ancient streambed of the Colorado River. The water is pumped from

two wells located near each water treatment plant. These wells range in depth from approximately 300

feet to 500 feet. Although the minimum depth to groundwater is about 160 feet at WCA and 250 feet at

KFR, our tap water is drawn from approximately 250 to 450 feet below the ground surface, respectively.

The pumped water is then treated through an electrodialysis reversal (EDR) unit at both WCA and KFR

treatment plants to provide quality drinking water.” https://ypg-environmental.com/files/WCA_KFR_2017_CCR.pdf

Given the hydrologic connection between YPG’s groundwater sources and the Colorado River, I wonder how the future negotiations will address this as well as the military’s involvement in these negotiations. How will any groundwater pumping, particularly on the Arizona side of the river, be addressed if this pumping affects Colorado RIver levels? Are there parallels with the issues in the current Supreme Court case between Mississippi and Tennesee, https://wreg.com/2019/06/04/judge-to-report-to-supreme-court-on-memphis-vs-mississippi-water-rights-case/?