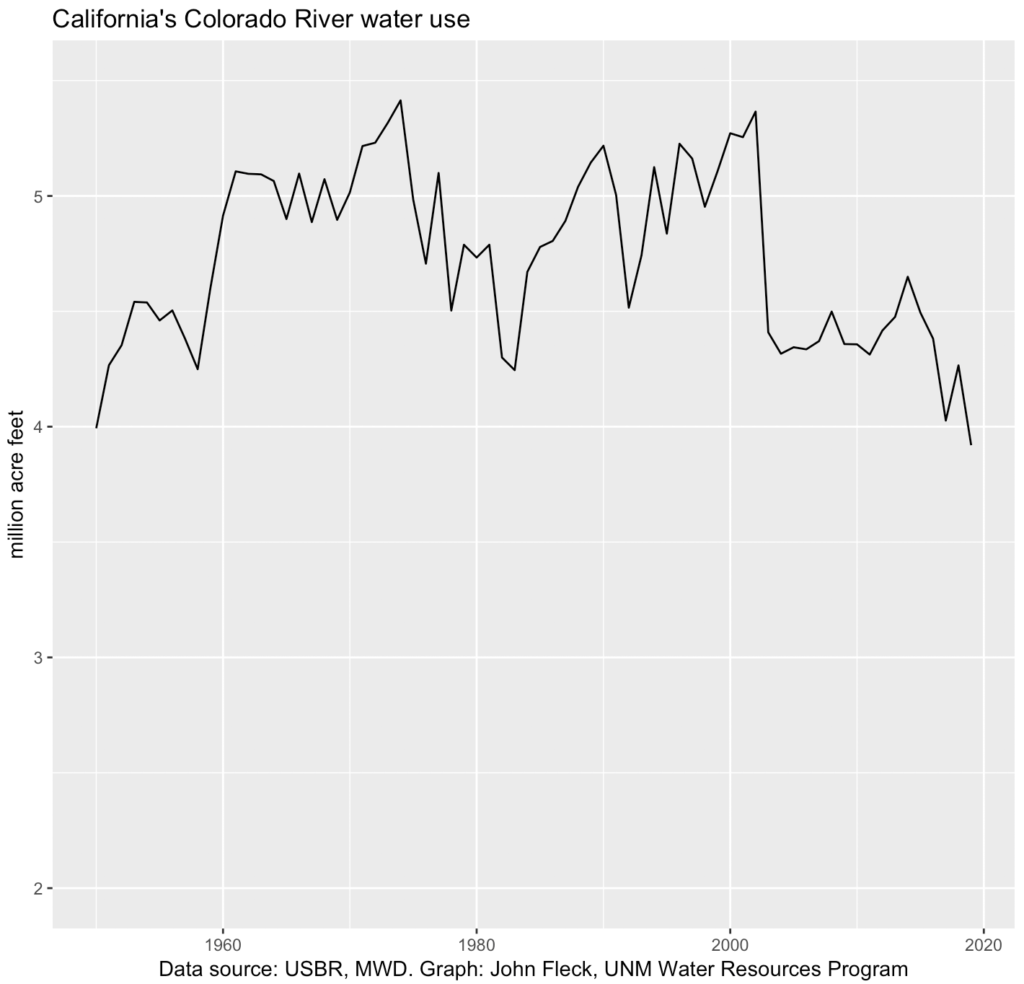

California’s use of Colorado River water this year is on track to be the lowest since at least 1949. (the latest forecast numbers are here)

My data on the early years is sketchy, but thanks to the folks at the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, who recently shared an excellent dataset they assembled some years ago, I’ve got data back to 1950. The current forecast of 3.92 million acre feet of California use of Colorado River water is lower than any year in that record.

California use of Colorado River water

There are a couple of things going on here. First, a good Sierra Nevada snowpack meant the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California didn’t need as much Colorado River water this year. But the Sierra snowpack, while good, clearly wasn’t the largest since 1950, right?

The second and arguably more important reason is a point Eric Kuhn and I make in our new book Science Be Dammed. While much of the book is about the problem of ignoring science on the supply side, we also argue in its concluding chapter that we are at risk of ignoring science on the demand side as well. Simply put, water use is going down. Here’s a squib from the book’s closing chapter:

There also is an empirical reality on the water demand side that has been insufficiently taken into account, but which provides a significant opportunity to help solve the river basin’s problems once we are willing to take it seriously. The widespread presumption that population growth means growing water demand drives much of the politics of water planning in the Colorado River Basin. But it is wrong. Simply put, we are consistently using less water. In almost all the municipal areas served with Colorado River water, water use is going down, not up, despite population growth. Water use in the basin’s major agricultural regions also is going down, even as agricultural productivity continues to rise. This is not limited to the Colorado River Basin. Such “decoupling” between water use, population, and economies is common across the United States.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot as I prepare for the this month’s Las Vegas gathering of the Colorado River Water Users Association. I’m moderating a sort of “what happens next” panel as we start talking, post Drought Contingency Plan, about the next steps in negotiating a new framework for post-2025 river governance.

We have some obvious stuff to talk about:

- disagreements over how to interpret the Colorado River Compact’s language about the Upper Basin’s obligations to send water downstream to the Lower Basin (see this from Anne Castle and myself discussing the legal issues involved)

- disagreements over how to interpret Upper Basin obligations under the Mexican treat (Eric and I wrote some stuff here about that)

- the question of how big a river we need to be planning for – what’s the range of future flow scenarios we have to prepare for (yeah, you knew another link to stuff we’ve been writing was coming – this with Eric, Brad Udall, Dave Kanzer, and myself)

I’m hoping the discussions at CRWUA and after take seriously this remarkable shift we’re seeing on the demand side. As Eric and I argue in the book, it opens important space for solving our problems if and when we acknowledge that we don’t need as much water as we thought.

Hi John:

Have you read “Silver Fox of the Rockies” the story of Delph Carpenter on of the major architects of the Colorado River Compact and the Memoirs of Herbert Hoover , Chairman of the CRCC from his Presidential Library as to the thinking of the time.

Low flush toilets, fewer lawns and/or more discipline on watering, low flow shower heads, recycling at car washes,

non-potable water at golf courses, fewer pools, higher water rates, not letting taps run, repairing leaks in distribution lines, better water meters, more showers than bathes…

What else?

Compared to other countries per capita use there is a lot more reduction possible.

Use point of use underground irrigation and ag could make huge reductions. If irrigation water had a price then investing in irrigation improvement would pay for itself.

Thanks for sharing the concluding punch line to your new book. Can you address how much of the drop in agricultural water use is driven by a change in crops and corresponding change in the type of irrigation? I’m thinking, for example, about the recent trend to replace rice fields in the Sacramento Valley with almond orchards. Those orchards are drip irrigated, and sometimes that’s characterized as more “efficient” but that perspective discounts the ecosystem benefits that come along with flood irrigation and are lost with the switch to drip irrigation.

Pingback: Dave Marston: A clear warning about the Colorado River - The Salt Lake Tribune