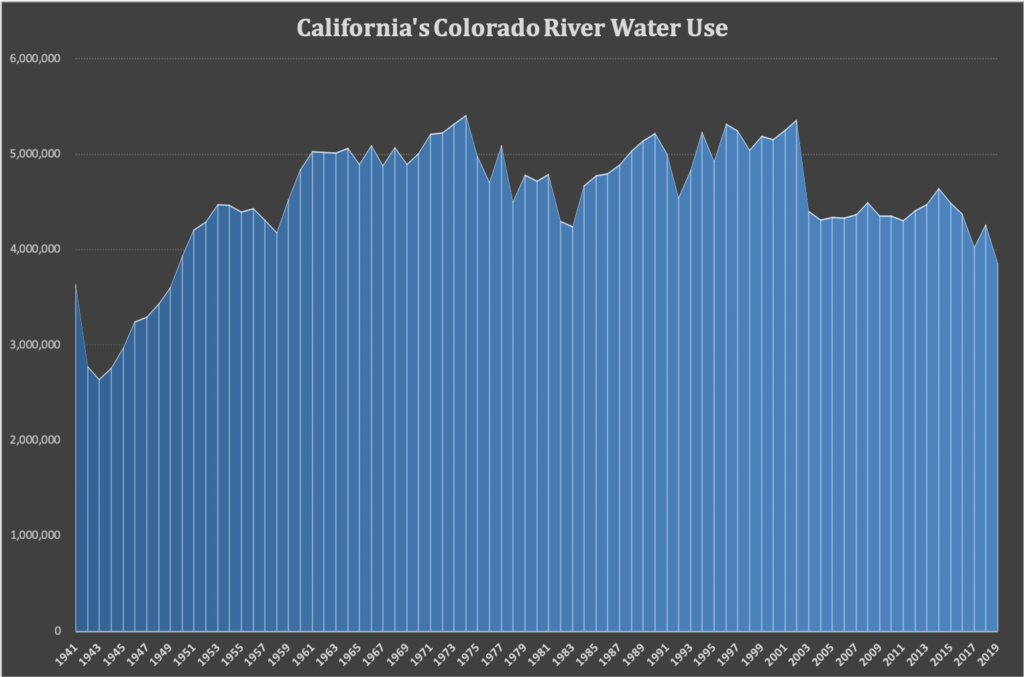

Data: Metropolitan Water District of Southern California; USBR. Munging together of datasets by John Fleck, University of New Mexico Water Resources Program

While Colorado River water management eyes were focused elsewhere this year – on the big snowpack up north, or the chaos success of the Drought Contingency Plan – California has quietly achieved a remarkable milestone.

Its use of Colorado River water in 2019 will be 3.858 million acre feet. The last time it was below 4 million acre feet was 1950, as the state’s big diversions – the All-American Canal and the Colorado River Aqueduct – were ramping up.

In our new book Science Be Dammed: How Ignoring Inconvenient Science Drained the Colorado River, Eric Kuhn and I make the obvious plea that decision-making going forward must take seriously the hydrologic science: that the Colorado River never had the water the planners schemed for in the 1920s, and that climate change makes that reality worse. But we also include a plea for taking demand-side science seriously:

There also is an empirical reality on the water demand side that has been insufficiently taken into account, but which provides a significant opportunity to help solve the river basin’s problems once we are willing to take it seriously. The widespread presumption that population growth means growing water demand drives much of the politics of water planning in the Colorado River Basin. But it is wrong. Simply put, we are consistently using less water. In almost all the municipal areas served with Colorado River water, water use is going down, not up, despite population growth. Water use in the basin’s major agricultural regions also is going down, even as agricultural productivity continues to rise. This is not limited to the Colorado River Basin. Such “decoupling” among water use, population, and economies is common across the United States.

In the 2019 California data, I see four things going on, three on the municipal water use side and one on the agricultural.

Southern California municipal water management success

On the municipal side (which means the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California and its best pal the San Diego County Water Authority):

- A good snowpack in the Sierra Nevada meant Met got a 75 percent allocation from the California State Water Project, which moves Northern California Water to “the Southland”, as we used to call the state’s populous Southern California coastal plain. That’s not a great allocation, but it is a good one.

- Bangup water conservation success in Met’s service area – publicly available California data suggests total municipal water use across Southern California is essentially where it was back in the 1980s. It’s not clear where the floor is here, but California’s experience during their Big Drought of the teens suggests there is still room reduce water use even more.

- Aggressive efforts to maximize local supplies – desalination, wastewater reuse, groundwater contamination cleanup, stormwater capture. Expect these numbers to continue to go up.

The result of all that is that the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, which provides all the water to the coastal cities, will end the year at 536,726 acre feet of use, its lowest use of Colorado River water since 1958.

Southern California ag reducing its water use too

Meanwhile on the agricultural side, California’s big desert irrigation districts also are using less water. Total use this year by the “big three” – Imperial, Coachella, and Palo Verde – is 81 percent of the 2002 peak. A big part of that is the web of agreements among ag and municipal users that allowed California to step back in the early 2000s from its excessive past use of Colorado River water use. The deals are frequently characterized as ag-to-urban transfers, but the more accurate way of seeing them is finding ways to compensate ag communities for absorbing the cuts as California scaled back from 5-plus million acre feet a year of Colorado River water use to its legal entitlement of 4.4maf.

Not just California

California’s low use is the headline grabbiest, but Arizona and Nevada are also using less than their full allocation. As I write every damn chance I get, when people have less water, they use less water. This is the critical point in the bit I quoted above from our new book.

My lovely All-City bicycle atop Hoover Dam, with a bathtub ring in the background illustrating Lake Mead’s great emptiness.

This should in no way be read as a suggestion that all is fine. The obligatory pictures of Lake Mead’s bathtub ring I take every December while on my way to the Colorado River Water Users Association meeting show, well, a bathtub ring, seen from many angles. No way around that.

1,090.44

Mead is ending the year at elevation ~1,090 feet and a couple of inches above sea level (1,090.44 as of 6 p.m. Mountain time as I write this), which means the provisions of section III.E.6 of Exhibit 1 to the Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plan Agreement kick in:

In the event Lake Mead’s January 1 elevation in a given Year is higher than that projected in the preceding August 24-Month Study, any DCP ICS creation that would not have occurred in such Year if the DCP Contribution had been determined based on Lake Mead’s actual January 1 elevation rather than a projection will instead remain available as the type of ICS originally created to the extent such volumes are the result of conservation actions consistent with ICS Exhibits to the 2007 Lower Colorado River Basin Intentionally Created Surplus Agreement (2007 ICS Agreement).

I’ve read that paragraph now ~17 times and I’m getting a headache and that’s no way to spend New Year’s Eve, but it basically seems to be saying that all the August hoopla about the first mandatory DCP cuts is basically “meh” and we end up with more dusty regular old “intentionally created surplus” banked in Mead in the coming year, not the shiny new “DCP ICS” we’ve all been so excited about. But I am not a lawyer, and would be delighted if any of you who have passed the bar can help clarify my thinking.

An interesting exercise for the reader would be to look at the final pumping numbers to see if anyone backed off of their pumping in December to try to nudge the final number above 1,090. Arizona, for example, seems to have diverted ~100k acre feet from the river in December 2019, which is less than half of what it took in each of the previous five Decembers. An extra 100kaf would have been enough to keep Mead above the 1,090 threshold, but I haven’t looked closely at who within Arizona was taking what, nor thought through who might stand to benefit from section III.E.6. As I said, an interesting exercise for the reader.

Colorado River Basin storage – slightly more than half full

Total Colorado River system storage is ending 2019 at 52 percent of capacity. So slightly more than half full, or just a bit less than half empty, depending on your desired framing. My preferred framing is that we figure out how to walk and chew gum at the same time with this stuff – recognizing enormous success without losing sight of how large are the looming problems that remain.

The obvious solution if for California to desal their Colorado water needs and all states in the compact to share in the increased costs. California has plenty of extra water, it’s just salty. Arizona, Nevada and Colorado don’t have this option.

Desalination is only one small spoke in the wheel. For example, it would take 20 desal plants the size of Carlsbad to equal the California Aqueduct Diversion for one year. Where ya going to put them? Industrialize Southern California’s coast? And what are your going to do with the brine if the plants are inland? At some point augmentation has to come front and center, with Desalination as part of it.

Weaning CA and AZ off the “surplus” water is going to be tough. As in both States the trend is to rely upon groundwater pumping, which neither state regulate in a sustainable manner. In 20 years CA may come to grips, but, by then the aquifers will be severely diminished. AZ has yet to recognize the aquifers limited life span. The reality is that the “surplus” water simply allowed for the development of too many acres. Obviously, neither the River and the aquifers can support the demand. The rotational fallowing agreements within demand management seem like the logical trend for agriculture in the precipitation deficient areas. There’s a reason as the Saudi’s soon realized that they’d overdeveloped their irrigation resources and turned to exploiting U.S. crops. The systems can’t support the populations currently reliant upon them.

Pingback: How big was Lake Mead’s “structural deficit” in 2019? – jfleck at inkstain