The framing questions I’ve used for my work on water over the last decade go something like this:

- When the water runs short, who doesn’t get theirs? What does that look like?

Those are the motivating questions behind a new paper Anne Castle and I have written. We’ve also added an increasingly important third question:

- Given the answers to the above, what should we do now to prepare?

The paper, The Risk of Curtailment Under the Colorado River Compact, is available for free download at SSRN. (I think you have to sign up for an account to actually download the paper, but it’s free.)

Here’s the nut:

Water supply in the Colorado River could drop so far in the next decade that the ability of the Upper Colorado River Basin states – Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and New Mexico – to meet their legal obligations to downstream users in Nevada, Arizona, California, and Mexico would be in grave jeopardy.

Legal institutions designed nearly a century ago are inadequate to address the significant risk of shortfall combined with uncertainty about whose water supplies would be cut, and by how much.

This report indicates that declines in the Colorado River’s flow could force water curtailments in coming decades, posing a credible risk to Colorado communities and requiring serious consideration of insurance protection like demand management.

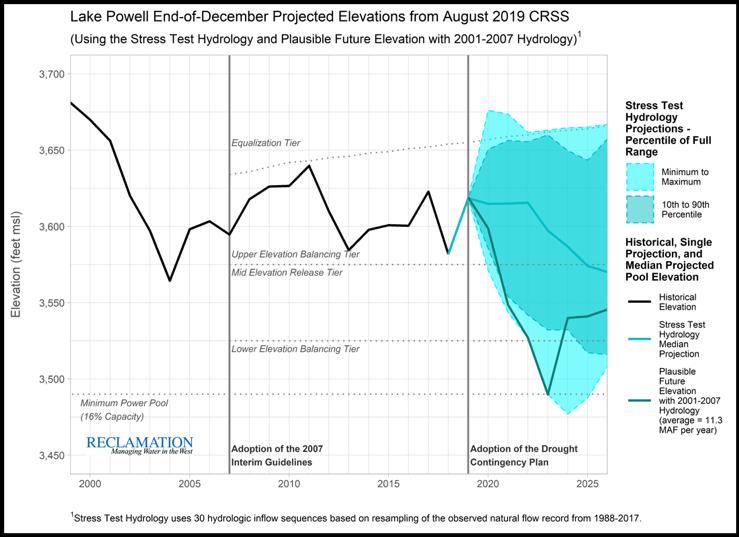

The risk is most easily understood in this graph, from new analysis done by the Bureau of Reclamation. It basically shows that a repeat of the most credible drought in the recent record, that of the early 2000s, could in a matter of a few years drop levels in Lake Powell to “power pool” – the level at which Glen Canyon Dam can’t generate electricity, and at which it begins to become difficult to get enough water through the dam to meet downstream delivery obligations under the Colorado River Compact:

Lake Powell risks. Source: USBR

The line screaming down toward the bottom, in sort of dark greeny color, is the one to look at. A repeat of the drought of the ’00s could, with just four dry years, drop Powell to “power pool” levels. This is not some scary future climate change scenario. This is something that has actually happened in the recent lifetimes of folks working on the river today.

Our contribution (and really all credit to Anne’s thinking here, she’s the one who did most of the heavy lifting) involves a detailed discussion bringing together well-understood climate science and hydrology risks with less well understood uncertainties in the legal system. We have a lot of people right now arguing essentially, “Well, the Law of the River shows those other people will have to have their water cut!” So lawyer up!

There be the dragons.

Anne and I believe it’s important to have a clear and public discussion about the significant unresolved Law of the River questions as well evaluate our hydrologic risk, so we head into the next phase of Colorado River management discussions with our eyes fully open.

We shouldn’t over-emphasize scary worst case scenarios, because the odds that we’ll be on that worst case line are low. But they are not zero (this is a drought that actually happened not that long ago!), and failing to have a plan seems like something worth trying to avoid.

Among the options Anne and I consider:

- “Demand management” – essentially reducing water use now and banking the savings as a hedge. This has been done with great success in the Lower Basin, effectively avoiding the risk of curtailment there by banking water in Lake Mead.

- Negotiating broad agreements with the Lower Basin, trading off some of our risk against some of theirs.

- “Going bare” – deciding that the costs of insurance (by “insurance” we mean foregoing water use now as a hedge against future risk) are too high.

Alternative 4, sadly unmentioned by Fleck, would be dumping the current Compact and replacing it with something based on population, agricultural productivity and other things.

Stuff talked about, among others, by the “out of date” Reisner.

Of course, Fleck never mentioned climate change until the very end of his first book, written years after the second edition of Cadillac Desert, speaking of being out of date … when printed.

I suggest the states, and Mexico, have their allocations reduced now based on the near term expectation of the river capacity. I also suggest that the states rework their quantities within their borders. The picture will look different with the real numbers.

I don’t see why there is an upper and lower division, except to have some logic for maintaining levels in the two big reservoirs. We are all in this together.

I can see a way to narrow Lake Powell which could maintain more elevation of the pool relative to the openings to the penstocks. Power production, water transit to Mead, and reduced evaporation could be achieved.

Intrastate fee structures for water use should be instituted to encourage conservation and provide funds for efficiency improvements.

Development and population growth should be halted.

I think the states need to make the determination about how water will be used within their borders. The basin is overdeveloped in general relative to available water. No state was forced to develop. This is the Tragedy of the Commons writ large. So is Global Warming.

It was always just assumed that the Upper Basin, where the majority of the water originates, would be able to provide. Since the Basin is roughly cut in half a 50% allocation might be carried on through. ie: In a call scenario A determination could be made of the total available water. The lower basin would have to reduce it’s usage by the amount of the call.

A call by itself isn’t a guarantee delivery of a specific quantity. The Lower Basin needs to be better prepared in the event the water isn’t there, and won’t be flowing downstream. The Upper Basin can’t deliver what doesn’t exist.