Walking across the University of New Mexico campus yesterday afternoon on my way to orientation for our incoming UNM Water Resources Program students, at precisely 3:10 pm MDT, a friend sent me a historic text message: “1089.4”.

Translated from the native language of the Colorado River Water Nerd, “1089.4” means “The surface of Lake Mead in the Bureau of Reclamation’s August 24-month study is forecast to end the year at less than 1090 feet above sea level, triggering the first mandatory cuts in the long history of the Law of the Colorado River.”

Below we will discuss quibbles with two of the words in that sentence: “first” and “mandatory”. But in my struggle to distill the complex into overly simple messaging that I can bang home in the style of the newspaper writer I once was – yes, this is historic.

This almost didn’t happen. When the DCP was signed in May, the Bureau of Reclamation was forecasting that Mead would end the year at elevation 1084.9, more than five feet below the trigger for mandatory cutbacks. Yesterday’s forecast was nearly five feet higher, just barely below the cutback trigger. But we’ve had a really wet year, haven’t we?

But 2019’s been really, really wet, right?

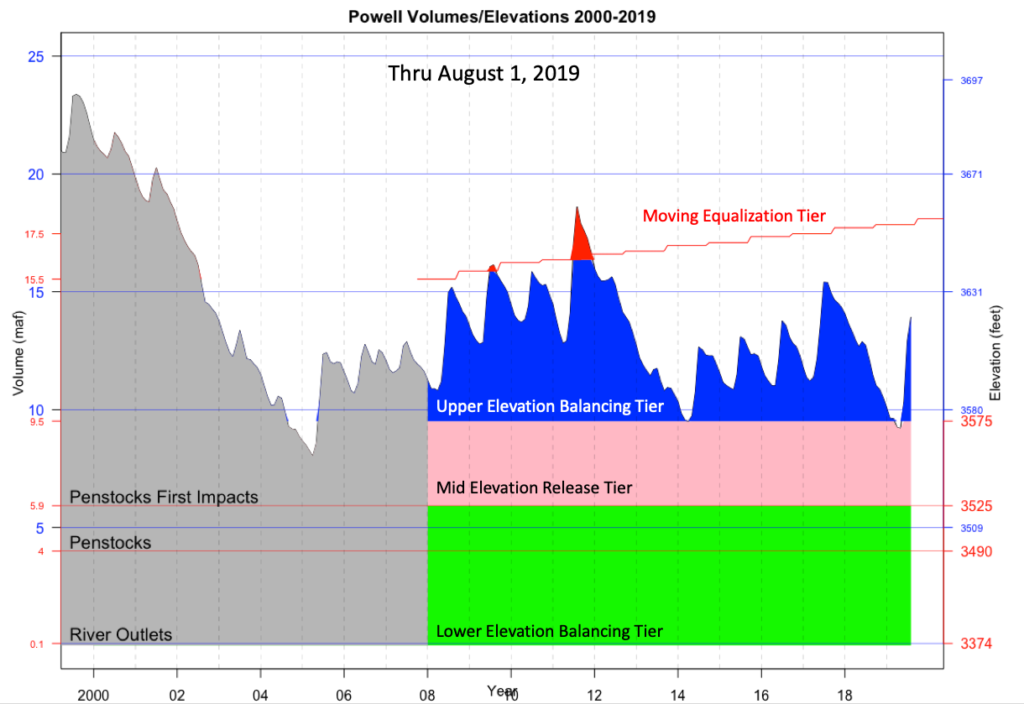

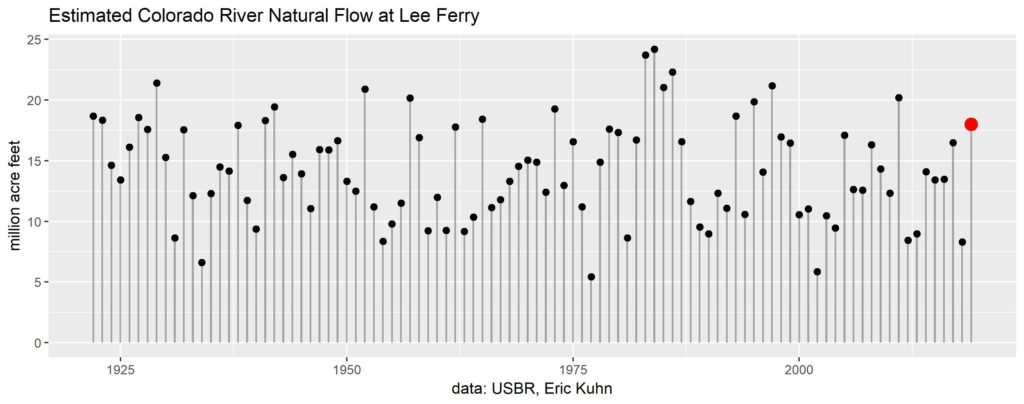

Not exactly. Some really helpful back-and-forths by email and telephone the last few days with Colorado State’s Brad Udall and my coauthor Eric Kuhn (buy our book, soon) has convinced me that a lot of the rhetoric about a giant snowpack and booming runoff, including some of my own, has not held up terribly well. Here’s a super helpful graph Brad made showing elevations in Lake Powell:

Yes, Powell is up this year, but it’s just a 22 percent above the long term average, nothing like 2011 and not all that much higher than 2017. I guess it seemed to me like a lot of water because the 21st century has been so dry.

The main reason Mead is ending the year so much higher than the May forecast is a) a reduction in Lower Basin use as compared to the May forecast, and b) an increase in tributary inflow below Glen Canyon Dam. That combination came within half a foot of Lake Mead elevation of saving me the need to write this tangled blog post.

I prefer to call the DCP cuts “mandatory”

There’s been a weird linguistic thing going on in the news coverage of 1089.4, with some writers characterizing the coming reductions of water use as “voluntary”. It’s easy to get sidetracked in a twisted binary linguistic argument about whether the cuts are “mandatory” or “voluntary”, which is best sidestepped by being explicit about the actual characteristics of the thing that is happening here.

In recent years, including this one, the states of the Lower Colorado River Basin have been doing a bangup job of using less water. No one is forcing them to, so the term “voluntary” seems to pretty clearly apply. Importantly, this means that they are not required to do this, and there are no guarantees that in coming years they would.

In May, all the states signed an agreement explicitly laying out rules that would cut their water use when Lake Mead is below 1090. Lake Mead will be below 1090. So the rules now require Arizona, Nevada, and Mexico to reduce their water use. Rather than hope for voluntary reductions in 2020, we can all count on the cuts because the rules require them. This carries an important characteristic of “mandatoriness” to me.

Did the states agree to the rules? Yes. Does that make them voluntary? Sure, whatever, I guess this has some characteristic of voluntariness too. But by this linguistic argument, we’d have to call Interior Secretary Gale Norton slashing California’s deliveries to L.A. through the Colorado River Aqueduct Jan. 1, 2003 “voluntary” because California had agreed in 1928 to the rules Norton was invoking. All the mandatory cuts we can see out there in the future of the Law of the River – an Upper Basin Compact call being the most obvious – would under this linguistic interpretation count as “voluntary” because they grow out of enforcement of rules to which the states had previously agreed.

It is the case that the states did come together to agree to these cuts, and there is voluntariness about that process that matters. Still, the fact that we now have enforceable rules that create requirements seems the salient point here, whatever words we use to describe them.

But is this really the first time we’ve had mandatory cuts?

So I guess now that I think it through, that “first time” thing was a bunch of crap designed to sell newspapers. As I acknowledge above, Gale Norton forced California to reduce its Colorado River water use from more than 5 million acre feet to 4.4 million acre feet back in 2003.

In thinking it through to write this post (folks this is why I blog) I’ve clarified my own thinking from the bombastic “OF COURSE IT’S MANDATORY” thinking of intemperate afternoon tweets. The voluntariness of what is happening now, as compared to what happened with California in 2003, seems relevant.

Maybe we could call it the first time the states have voluntarily agreed to mandatory cuts?

* “Ill-named” because this isn’t about drought. This is about us using too much water.

Perhaps this will encourage the “Water Managers” to keep their collective feet on the gas pedal. There are some hard decisions ahead regarding the 2007 interim guidelines re-up that are going to have to be faced…finally?… for the future health of the Colorado River Basin.

I disagree that this was the “first” time the States voluntarily agreed to mandatory cutbacks. The States agreed to cutbacks in 2007 with the implementation of the 2007 Interim Guidelines. The DCP overlays additional cutbacks to the 2007 Interim Guidelines to reduce the probabilities of Lakes Mead and Powell falling levels where water deliveries and power generation would be severely impacted. The DCP is the first time California voluntarily agreed to mandatory reductions..

Another reason for less water use in the Lower Basin is that California’s Sierra Nevada received above nornal snowfall. California’s State Water Project was able to deliver 80 percent of their contractors allocations. Thus the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California was able to reduce their deliveries from the Colorado River and take more deliveries from the State Water Project.

Don, thanks, the “first” I’m talking about here is the first time actual cuts have happened in response to one of those voluntary agreements – “triggering the first mandatory cuts in the long history of the Law of the Colorado River”. We haven’t had any cuts yet as a result of the ’07 guidelines, and there are arguably other places in the Law of the River as well where we’ve got an agreement that would require cutbacks, but where those cutbacks haven’t yet been triggered.

Pingback: Colorado River water reduction rules: not quite voluntary, not quite mandatory – “vandatory”! – jfleck at inkstain

John, we can argue about whether 2003 was an actual reduction, since California still got its full apportionment that year. But regardless, that wasn’t the first time the Secretary imposed mandatory reductions on lower Colorado River water users.

In May 1964, following a second consecutive year of low runoff (plus the fact that the gates had been closed at Glen Canyon to begin filling Powell), then-Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall announced a 10% reduction in deliveries to all lower basin contractors for the remainder of that year. In addition, Reclamation said it would charge all contractors for water ordered and available at Imperial Dam but not taken.

Both YMIDD and Yuma County Water Users’ Association challenged the Secretary’s action in court. Both lost. If you want to read the cases, they are available online:

http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=17219132847807526820&hl=en&as_sdt=2&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr

http://www.leagle.com/decision/1964779231FSupp548_1671

Curiously, even after nearly 20 years of continuing drought, Reclamation today does not charge water users for water ordered but not taken, even though its authority to do so has been upheld.