By Eric Kuhn

Delphus Carpenter. Picture courtesy Colorado State University library

Colorado attorney Delph Carpenter (1877-1951) is given credit as the driving force behind the 1922 Colorado River Compact, a much-deserved accolade. Had the compact negotiators actually listened to him, however, both basins would be better off today. Before the compact negotiators settled on the deal we are now trying to live with, Carpenter proposed a far simpler arrangement that, in retrospect, might have been better. Had they listened to him and adopted his idea, the Upper Basin today would not be facing the daunting task of implementing demand management to maintain critical storage levels in order to meet its downstream obligations and the Lower Basin would have more water and fewer shortages.

The 1922 compact as it was signed in November 1922 was not the compact Carpenter wanted when the negotiations began in the previous January. He was a fierce advocate for state sovereignty over all the waters that originate or flow through a state, but Carpenter knew he might be on the wrong side of the United States Supreme Court on the matter. He was Colorado’s lead attorney in Wyoming v. Colorado, a case involving the Laramie River, a small and relatively unknown stream that flows north out of the mountains west of Ft. Collins into Wyoming where it eventually joins the North Platte River near Wheatland.

In the early 1900s, A Colorado developer proposed a project that would divert water from the Laramie River Basin into the adjacent South Platte River Basin. In 1911, Wyoming went to the U. S. Supreme Court to protect water rights that had already been perfected in the Wheatland area. As the Colorado River negotiations began, the case had been through two oral arguments, but had not yet been formally decided. Carpenter feared that since both Colorado and Wyoming were prior appropriation states, the court would apply the doctrine to the Laramie on an interstate basis, undermining his cherished state sovereignty and, on the Colorado River, giving the advantage to faster growing lower river states.

The Laramie case loomed as representatives of the seven Colorado River Basin states came together to negotiate what would become the Colorado River Compact.

After joining Utah commissioner R. E. Caldwell during the sixth Compact Commission meeting to block a proposal to apportion water to individual states based on the amount of irrigable acreage within each state, during the seventh meeting, Carpenter made his move. Carpenter’s proposal was relatively simple. He suggested that the lower river states should allow the upper river states to develop and use water within the basin unimpeded by the states of the lower river –“the construction of any and all reservoirs or other works upon the lower river shall in no manner arrest or interfere with the subsequent development …of the upper states or the use of water therein….”

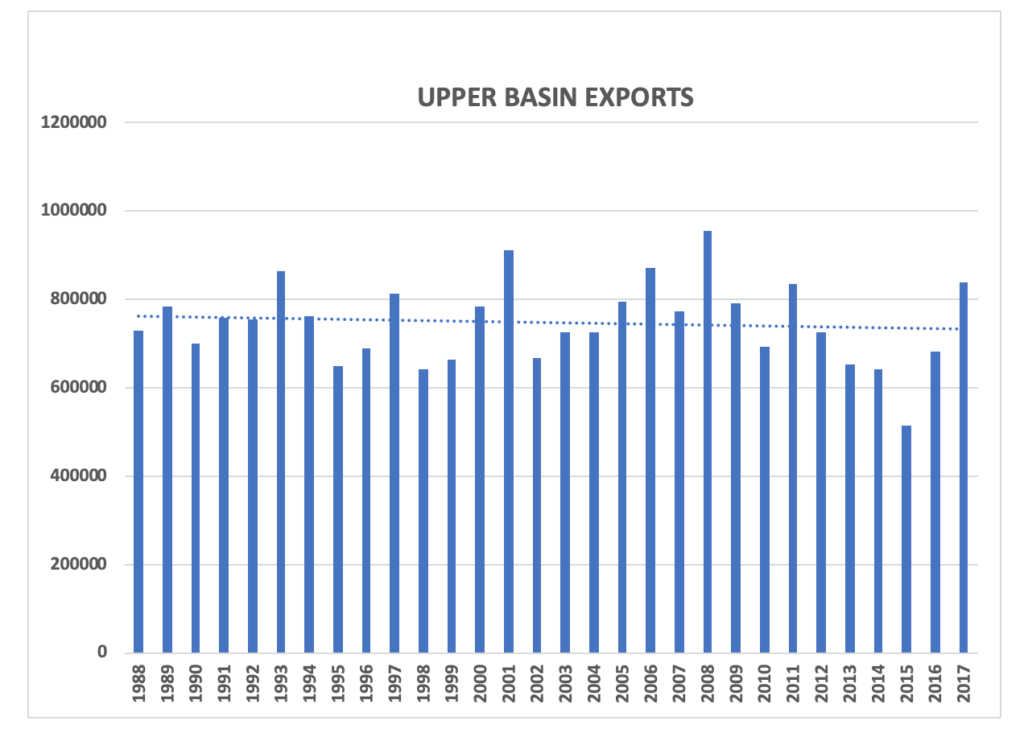

In return, Carpenter said, the upper river states would do the same- “give you absolute free unbridled rights, all objections withdrawn…” The upper river states would not litigate or oppose in Congress, any development in the lower river. Carpenter made the case that due to the canyon and mountainous topography, climate (limited growing season), and because of return flows, water use within the upper part of the basin would have little impact on the supply of water to the lower river- “the areas which may be irrigated and the consumption …. so limited by nature, that the states of origin will never be able to beneficially use even an equitable portion of the waters …. of each.” When pressed by Commission Chairman Herbert Hoover, Carpenter acknowledged that because exports out of the basin were fully consumptive the upper river would agree to limit the amount water moved across the continental divide. In Silver Fox of the Rockies, historian Daniel Tyler suggests that Carpenter and his fellow upper river commissioners would have accepted a limit of 500,000 – 600,000 acre-feet per year, about 25% less than the current exports.

Commissioners from the lower river rejected Carpenter’s proposal countering that without an overall limit on upper river use, they would not have the certainty necessary to finance their proposed projects. In June 1922, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favor of Wyoming and applied the concept of prior appropriation to the Laramie River as a whole, confirming Carpenter’s fears. The decision forced him to change tactics. When the commissioners reconvened in Santa Fe in November 1922, building on a proposal by the Reclamation Service’s Arthur Powell Davis (now Bureau of Reclamation) to create a compact among the two basins, Carpenter made a new proposal which became the framework for the compact that was ultimately approved. Carpenter proposed the basins be divided at Lee Ferry (a mile downstream of Lee’s Ferry), the Upper Basin would, in Carpenter’s words, “guarantee” a 10 year-flow at Lee Ferry (the negotiated number ended up at 75 million acre-feet), and each basin would share any future treaty obligation to Mexico.

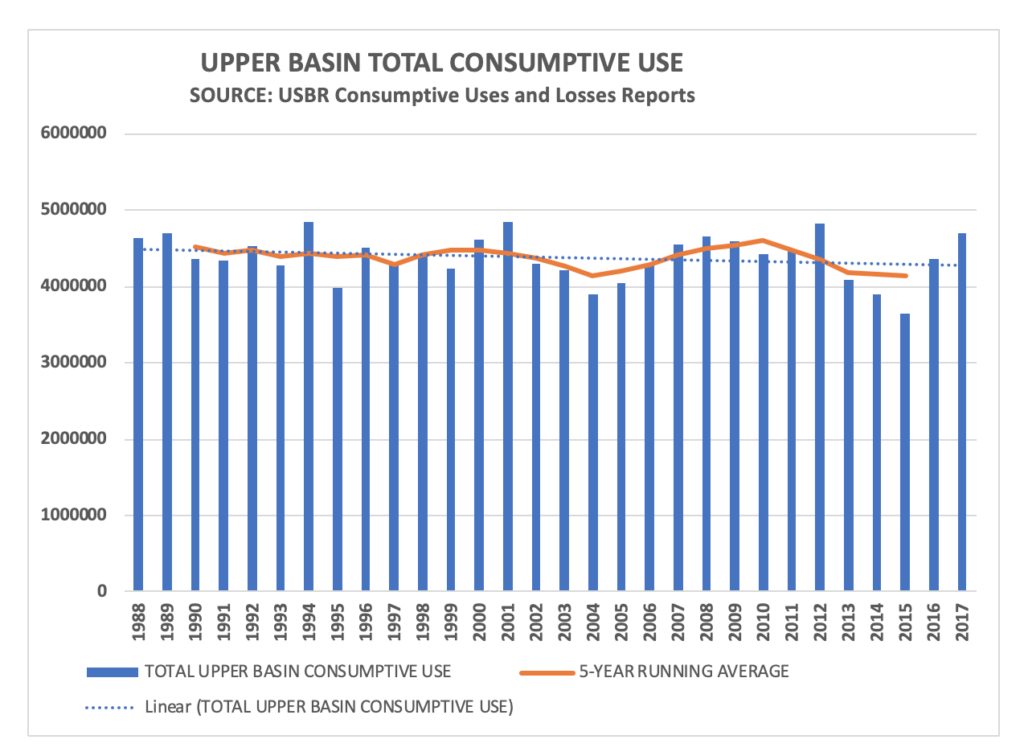

Today with the specter of climate change reducing the water available from the river, perhaps the key concepts and messages from Carpenter’s preferred compact deserve a second look. As Carpenter suggested, consumptive uses in the Upper Basin have been self-limiting. After a building spurt triggered by federal funding made available under the 1956 Colorado River Storage Project Act that lasted from the late 1950s through the mid-80s, the total consumptive use of water in the Upper Basin from 1988-2017 has been flat or even slightly declining.

Upper Basin water use

The reasons are not difficult to understand. The last big federally subsidized irrigation projects were completed in the late 1980s and early 90s. As were the last big transmountain diversion projects. In-basin municipal growth has been strong, but since much of it is occurring on lands that were previously under irrigation, the net impact of residential growth on water consumption is small. The energy sector, once projected to be a major user of the Upper Basin’s share of water, is now more likely to accelerate the decline in total Upper Basin use. Natural gas and oil production consumptively uses very little Colorado River water. And, more importantly, the basin’s aging and uncompetitive thermal power plants, which at one time were consuming over 170,000 acre-feet per year, are being rapidly decommissioned. Within a decade, total use by thermal power will likely be less than 50,000 acre-feet per year (if not zero).

In theory, new export projects out of the Upper Basin to meet the needs of the booming Colorado Front Range and Wasatch Front could be a driver for new consumptive uses, but reality suggest otherwise. There are currently only three export projects in the planning or permitting process; Denver Water’s Moffat System Expansion project, Northern Water’s Windy Gap Firming project, and the State of Utah’s Lake Powell Pipeline. The net additional consumptive of the first two projects is small, no more than about 20,000 acre-feet per year. The Lake Powell Pipeline will divert about 80,000 acre-feet per year to the St. George area, but it may not really be an export project. The water it diverts will be used in the Lower Basin. Like overall Upper Basin consumptive uses, since 1988 the trend for exports has been flat or slightly declining.

Upper Colorado River Basin Exports

The Lower Basin’s total mainstem use is also on a recent downward trend primarily because of the conservation measures implemented to preserve storage in Lake Mead and less evaporation due to reduced storage levels. There are insufficient data on Lower Basin tributary uses to make any trend conclusions. Despite this progress, when reservoir evaporation and tributary uses are included, the Lower Basin is consuming, on average, more than ten million acre-feet per year.

The current situation on the river raises the basic question of equity between the two basins that Carpenter recognized a century ago. The Lower Basin is using more than its 8.5 million acre-feet apportionment under the 1922 compact. The Upper Basin is using far less than its 7.5 million acre-feet, about 4.3 million acre-feet per year. Yet, with fixed obligations to the Lower Basin and Mexico under the 1922 compact, the Upper Basin still bears the brunt of the climate change risk. To avoid what could otherwise be inevitable future conflict, basin water leaders should carefully consider the wisdom of Delph Carpenter’s preferred compact and devise an approach that gives each basin the flexibility to live with the water they currently have and stay out of each other’s business.

Flip side is, as Reisner pointed out in Cadillac Desert, and yes, I’ve seen what you wrote about it a few years ago, you can’t grow shit in the upper basin like you can in the lower. (And an extra degree or so of climate change already hasn’t changed that.)

Sure, they grow alfalfa down in the Imperial Valley with river water when it could have better uses; they grow alfalfa in Wyoming with it too, and at least in California, you can get half a dozen cuttings of the alfalfa a year, not one or two.

As for non-ag use, well, the great majority of the basin’s population is in the lower basin. So, no, a new compact should first redefine usage ratios and THEN get each basin to stay out of the other’s way.