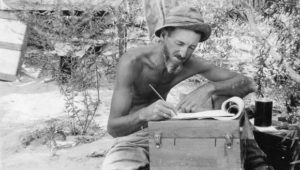

E.C. LaRue at Diamond Creek. Photo by R.C. Moore. 1923. Courtesy USGS

USGS hydrologist Eugene Clyde LaRue’s December 1925 testimony before the U.S. Senate Committee on Irrigation and Reclamation set my storyteller’s nerves tingling.

It was a critical moment in the history of the West, as Congress deliberated turning the abstract water allocation rules of the Colorado River Compact into appropriations and concrete.

Y’all probably know the conventional telling of the story of the allocation of the Colorado River’s waters, a story I told this way myself in what I now call “my last book“.

At the time the Colorado River Compact was negotiated, streamflow data was sketchy, based primarily on a single gauge at Yuma, Arizona, near the bottom end of the river system. But twenty years of data was sufficient to give the compact’s negotiators confidence that they had at least 17 million acre-feet per year on average to work with, and likely more.

At the time I wrote that line in 2015 in Water is For Fighting Over, I had a copy of LaRue’s 1916 USGS Water Supply Paper No. 395, The Colorado River and Its Utilization, on a shelf above my computer. But until I began collaborating with Eric Kuhn back in 2016, I didn’t fully grasp the importance of LaRue’s work. As early as that 1916 report, LaRue had raised cautions about the sufficiency of the Colorado River’s supplies. By 1925, they had moved from cautions in dense USGS report tables to full-throated Senate testimony. “For many years,” LaRue told the Senators, “it has been reported that there was plenty of water for all.” LaRue then turned picked up a copy of WS395, his 1916 report, quoting a passage that could or should have been known to the Compact’s negotiators when they gathered in 1922 to carve up the Colorado River’s waters. “The flow of Colorado River and its tributaries,” LaRue told the Senators, “is not sufficient to irrigate all the irrigable lands lying within the basin.” LaRue’s cautions came fully three years before Congress ratified the Compact and plunged us headlong into decades of dam and canal building that overshot the amount of water the Colorado River had to fill them.

The University of Arizona Press will publish Science Be Dammed: How Ignoring Inconvenient Science Drained the Colorado River, by Eric and myself, this fall. We’ll tell you the story of LaRue and others who followed in his wake, and the important ways in which the use and misuse of science is now embedded in the problems of 21st century Colorado River governance as we try to untangle the knots left by the river’s overallocation.

As a writer, I love Congressional hearings – little theatrical set pieces where policy dramas play out. As a numbers nerd, Eric is drawn to the tables embedded in those hearing transcripts, the graphs, the empirical dramas as those measurements played out across the Colorado River Basin over the last century. Eric, who recently retired as general manager of the Colorado River Water Conservation District on Colorado’s west slope, is one of the river’s smartest people. He sees things in the numbers that I cannot until he shows them to me. For a Colorado River nerd like myself, the chance to collaborate with Eric these last three years has been a blast.

We look forward to sharing with y’all what we found.

Congratulations, great title, and that’s a lot of ya’lls for a Californian!

“Y’all” may be my favorite word. Or is it words?

May I post some or all of this on my Facebook page?

Looking forward to the book

Geri – Absolutely, I’d be honored/delighted!

I look forward to reading it!

Best,

D

Pingback: I'll be talking about the new book this Friday (Feb. 22, 2019) in Albuquerque - jfleck at inkstain

Pingback: Why Does the Lower Basin Need a Drought Contingency Plan? - jfleck at inkstain

Pingback: Cutting IID Out of the Lower Basin DCP Would Just Continue a Long Tradition in the Colorado River Basin – jfleck at inkstain

Pingback: Water is For Fighting Over, out in paperback tomorrow – jfleck at inkstain