I had one of those “I wish I was still a reporter” moments when Glen Duggins, at yesterday’s meeting of the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District board meeting, raised the issue of elk in Polvadera.

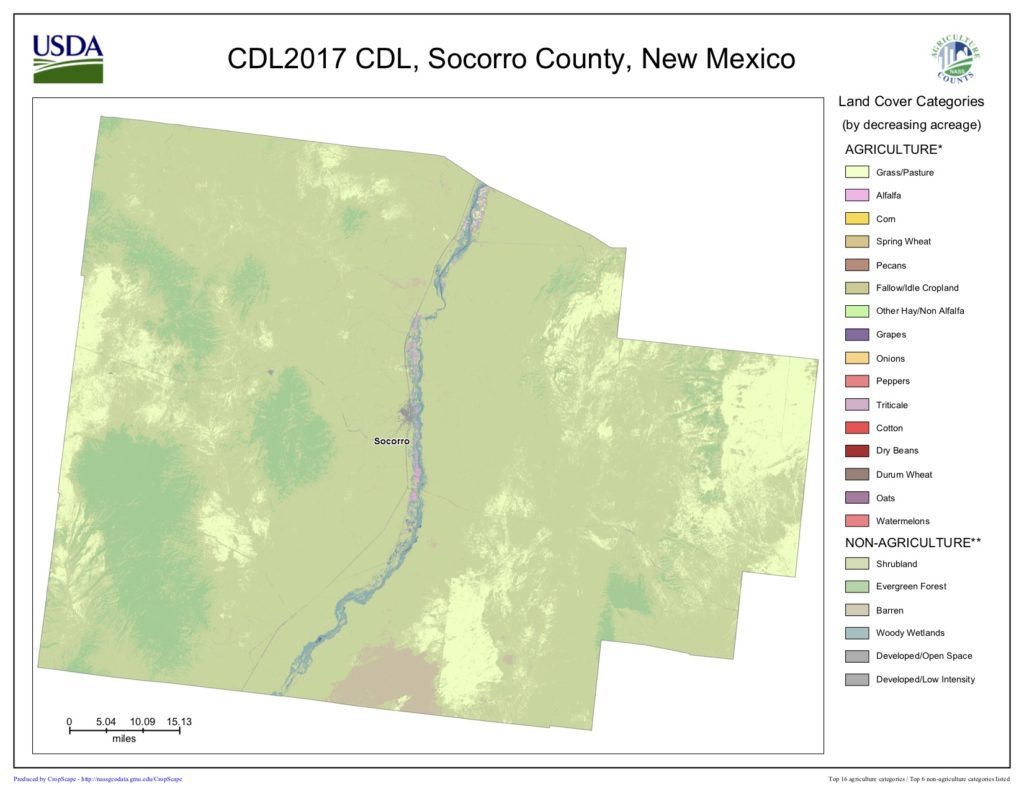

Polvadera is an unincorporated community along the Rio Grande, between the also unincorporated communities of San Acacia and Lemitar, strung out along the floor of the most productive farmland along this stretch of the river. Calling it “the most productive farmland” may be misleading, because the net cash farm income along this stretch of the river tends to be negative save for Socorro County. But this is not Iowa, and the sort of ag productivity numbers that shape the CBOT futures markets can’t tell us the full story of farming here. Which is why I perked up at the discussion of elk.

Duggins, a board member from Socorro County, had gotten a call from a constituent who was having trouble with elk raiding his wheat field. This is not large-scale agriculture we’re talking about. And the MRGCD is an irrigation, drainage, and flood control agency, not a game management agency. But the fact that it’s a very small farmer growing six acres of winter wheat to supplement his retirement income in some sense makes it all the more important, and sheds interesting light on questions of what water management and governance are really all about here in what we in New Mexico call “the middle Rio Grande valley”.

In my last job, as a newspaper reporter, I used to hang out at the MRGCD’s Monday afternoon board meetings when I could. It turns out that in my new job, as director of the University of New Mexico Water Resources Program, a couple of hours at the MRGCD board meeting also is time well spent. You get agency water manager David Gensler’s regular water reports – how much is in storage, when and where and how releases to the ditches for spring irrigation are progressing, and the important question in a dry year like this of how the summer season looks. Chuck DuMars, the former law professor who represents MRGCD (and many other important water agency clients, including California’s big Imperial Irrigation District), gives what often amounts to mini-seminars on the rich tapestry of New Mexico water law. Those are usually the main attractions for me.

But you also get governance at the retail level – complaints about which ditches are getting water when, the eternal discussion of ditch bank gates and public access, culvert repairs. And yesterday afternoon, elk.

Raids by elk onto the Socorro County valley floor have been an increasing problem over the last decades (yes, I wrote about this when I was at the newspaper – I’ve got links like this for many occasions!).

I am not a lawyer, but I’m pretty sure elk predation is not explicitly covered by MRGCD’s explicit statutory authorities. But in the midst of the hodgepodge of government entities whose duties encompass agriculture, MRGCD is arguably the most important. Socorro County’s human geography is defined by the narrow strip of green along the Rio Grande and the irrigation ditches that spread its water on the valley floor immediately surrounding it. The distribution of water both enables and constrains agriculture in all its forms in this part of the country, and therefore the place’s human habitation. So when the Polvadera farmer saw elk eating his supplemental retirement income, it was I guess natural to call Duggins. That is the importance of this story.

It’s not clear to me what a water agency can do about elk. But the MRGCD board’s Urban Affairs Committee pledged to look into it, there was a suggested field trip to check out the elk problem in person, and a charmingly lengthy discussion about ensuring that MRGCD staff with hunting experience and inclinations be included in the policy discussions of possible solutions to the Socorro County elk problem.

I love the pageant of democracy.

Your earlier article on elk at Bosque del Apache mentions: ” With most big predators gone, they have expanded into other habitats.” As I read your blog today I thought of the balance of elk and wolves in Yellowstone after wolves were reintroduced in the 1990’s. The presence of wolves kept the elk away from the riverbanks where they caused erosion and ate the stabilising willows and riparian vegetation that helped retain water via its roots. The elk moved back in the forest.

However your article mentions that elk used to live on the plains. Do you have any background info on that? And did there use to be wolves in NM Rio Grande Valley that would keep elk away? thanks for any info… Alison

What can you say about pecan farmers using Rio Grande water in the Rio Abajo, not just in the Mesilla Valley but on the west mesa south of Belen? The irrigation season starts March 1st or thereabouts, yet one pecan farmer that I know of got irrigation water in January, a situation that affects many farmers lacking the same benefits. Is the ill-will worth it in a time of drought even if the pecan farmer is trying to recoup losses following last season’s storm breach in the irrigation ditch?