I’ve been thinking about the central communication challenge as we face down yet another dry year amid the continued drumbeat of Upper Basin talk about finding new ways to take more water out of the Colorado River.

It goes back to something I wrote in my book:

Within the network of state and water-agency representatives working on Colorado River Basin problems, there is a clear recognition that eventually some sort of “grand bargain” will be needed that finds a way to reduce everyone’s water allocation. To keep the system from crashing, everyone will have to give something up. But each of the participants in that core network also understands the dilemma that follows: each must then go home and sell the deal in a domestic political environment that views the river’s paper water allocations as a God-given right.

I’m not sure that’s quite right in a couple of ways. First is the assertion of that the solution is some sort of “grand bargain”. In the two years since I handed off the manuscript for Water is for Fighting Over: and Other Myths about Water in the West to my editor Emily Turner at Island Press, I’ve come to a better understanding of the nature and value of incrementalism on the river – deals done from the bottom up, one irrigation district and municipality at a time, rather than the sort of top down solution the “grand bargain” phrase implies.

But my underlying point – that there is an understanding gap between people who work at the basin scale and those who use water at the local level – seems even more relevant to me today.

The Colorado is really just a 15 million acre foot a year river

The second weakness in that passage of the book is my assertion that everyone in “the network” really understands this dilemma – that the Colorado River Compact and the federal legislation and treaty that followed allocated 18 million feet of a 15 million acre foot river. I still want to think that everyone in that core group I describe in my book understands this, but there is a strong push from the people one layer removed in water governance – the city councils and irrigation district boards and state legislatures across the basin – to grab hold now of the water promised in the Law of the River. That provides a strong incentive for some of the people in the core network to avoid pursuit of grand bargains and honest recognition that it’s really just a 15 million acre foot river.

Decoupling is real

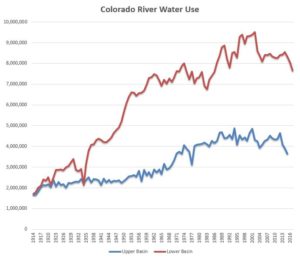

This problem is connected to a second, which has been the thing that most surprised me as I’ve traveled the West talking water since the book came out. People are often surprised by, and sometimes actually resistant to, the evidence for decoupling – the evidence that we’re actually using less water now, and that we’ve demonstrated communities’ ability to grow and thrive even as their supply of water has shrunk.

Repeat after me

Those of you who read my newspaper work over the years may have snapped to my schtick – saying the same thing over and over. I dressed it up in different outer garments, but my core messages were generally the same. I believe in the power of repetition.

So let me reiterate two points for emphasis:

- The estimated natural flow at Lee Ferry on the Colorado River in the 21st century has been 12.4 million acre feet per year.

- This is not an 18 million acre foot river.

- Upper Basin water use in 2015, the most recent year for which we have data, was 3.7 million acre feet, the lowest since 1977. Lower Basin water use in 2017 (again the most recent year for which we have data, LB accounting is done more quickly) was 6.8 million acre feet, the lowest since 1987.

- Decoupling is real.

Seems I may have buried the lead here, or “lede” as my annoying journalist friends insist on spelling it.

John, thanks for your work and research into one of the most important topics – water systems in evermore arid climates – confronting life as we have come to know it through river wrangling and manifest destinies.